The Whisper of Maize

-

Dates2019 - Ongoing

-

Author

- Locations Peru, Mexico

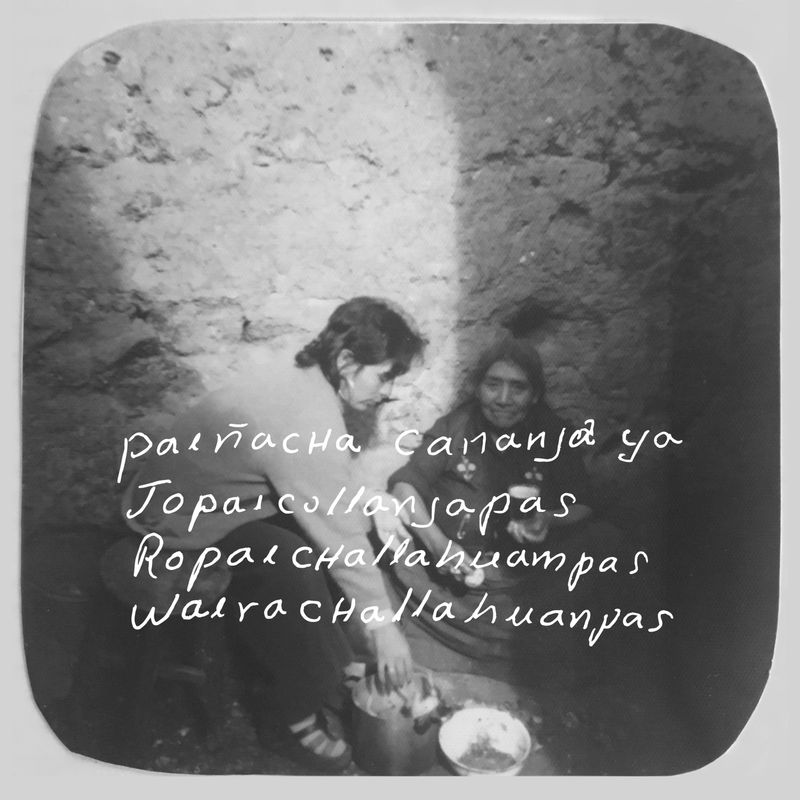

The protection of ancestral maize as a spiritual and ecological form of resistance. Guided by my grandmother’s memories, it follows Quechua–Wanka women who speak the language of the earth, safeguarding seeds through song, care, and continuity.

This project is born from the desire to return to a place that may no longer exist, except in memory, seeds, and songs. My personal search begins with my grandmother, who, whispering melodies, dreamed of her land of origin, of the wind brushing through the maize leaves. Her voice, her stories, and her personal archive guide my gaze as I pursue a path back through images and memories.

In the highlands of Peru, Quechua and Wanka elders continue to care for more than 54 native varieties of corn, seeds protected through over 7,500 years of agricultural and spiritual knowledge. Today, this living heritage is threatened by drought, state neglect, and the erosion of ancestral ways of life. Yet the land is still cultivated through ritual, patience, and collective memory. “We plant the seeds with the power of our singing,” says Magdalena, a Wanka elder.

Each variety carries its own shape, color, and spirit—each holds a story. What is being protected is not only biodiversity, but language, gesture, and ways of understanding the world. To work the land is to speak with it, to sing to it, and to listen—to practice the language of the earth so that the seeds may grow strong.

Through the strength of Quechua–Wanka women, I navigate an impossible homecoming: not a return to a fixed place, but a movement toward belonging, carried through care, ritual, and transmission. In times of environmental and cultural rupture, their acts of tenderness become radical—offering seeds, songs, and memory as pathways to remain human, and to imagine a future rooted in ancestral resilience.