Verdiana Albano: Between Two Cultures, Beyond Completion

-

Published6 Jan 2026

-

Author

- Topics Archive, Awards, Contemporary Issues, Daily Life, Documentary, Social Issues

Verdiana Albano's I Ain't From No East Coast reconstructs Afro-German history through fragmentation, family archives, and the absences official narratives leave behind.

A question had followed her for years: where do you come from? It stops being a request for information and becomes a call for definition. But Verdiana Albano’s work, I Ain't From No East Coast, echoes with a different answer, “located at the end of two cultures”—a phrase that does not offer resolution, but opens a tension.

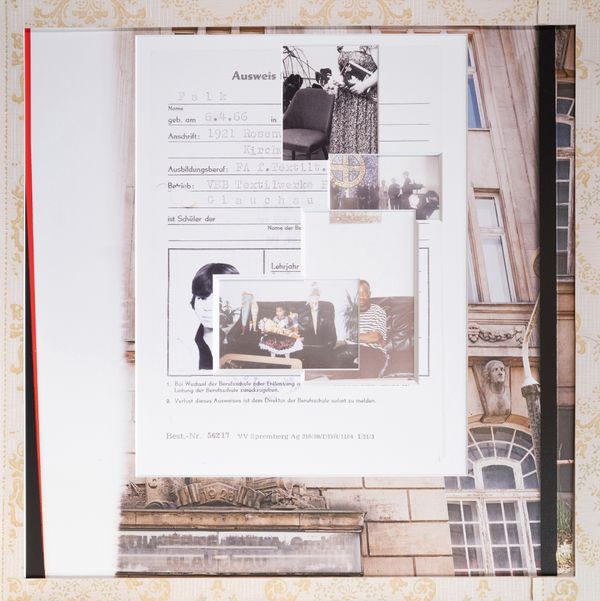

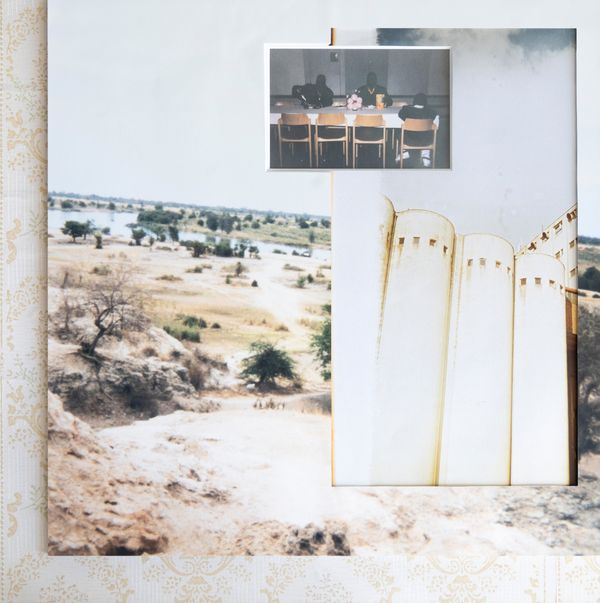

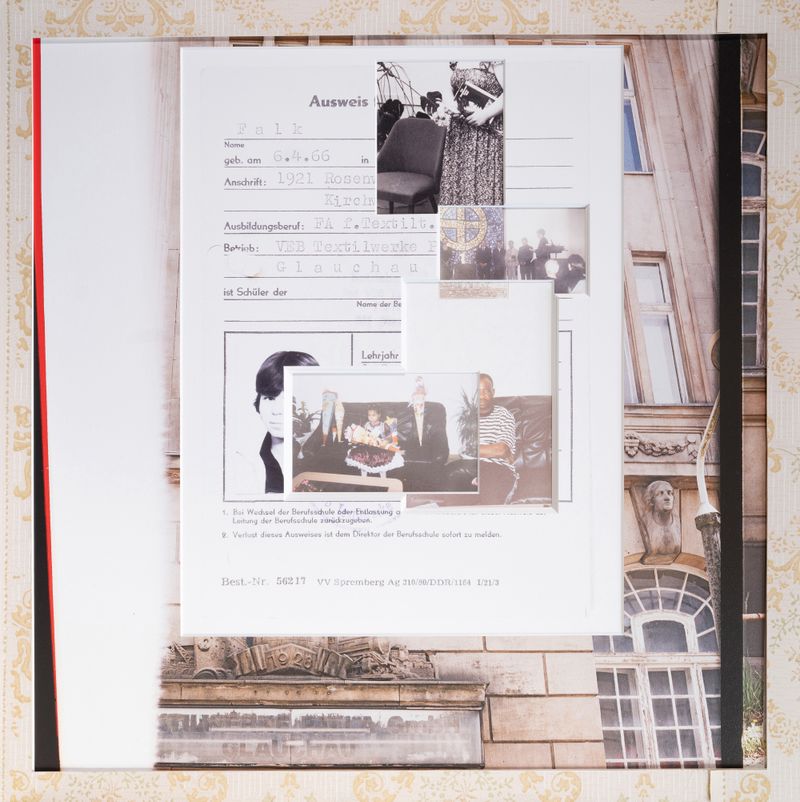

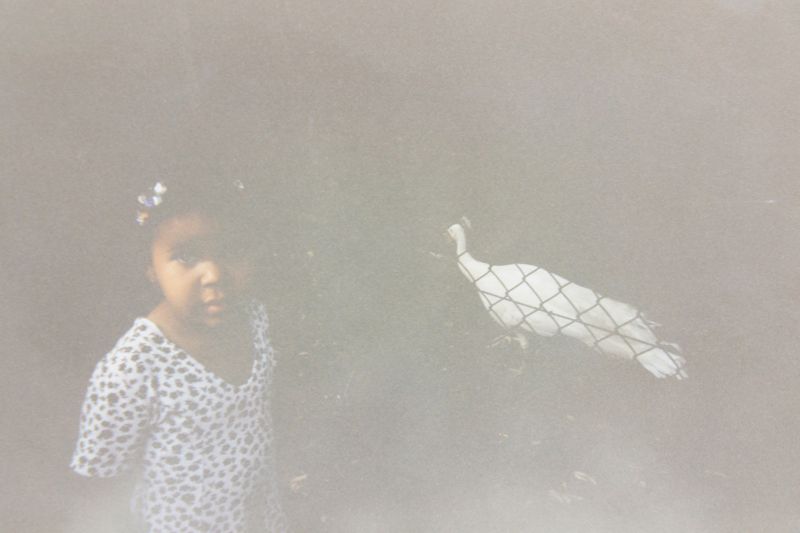

Rather than treating culture as something fixed, Albano’s work moves within uncertainty. Culture appears as something fluid, transforming. This sense of suspension is mirrored in her visual language. Nothing appears whole. Images overlap, documents interrupt photographs, surfaces conceal as much as they reveal. Albano describes this condition as a structure that reflects the way history itself unfolds—fragmented, layered, incomplete. Each image suggests that something remains hidden, just out of reach.

I Ain't From No East Coast is developed through three interconnected approaches. The first draws from Albano's family archive, using personal photographs as both evidence and absence. The second involves images taken at former VEB industrial sites in the former GDR—state-owned factories that once structured everyday life and later fell into abandonment after reunification. Visiting these sites decades later, she documents what remains and what has been erased.

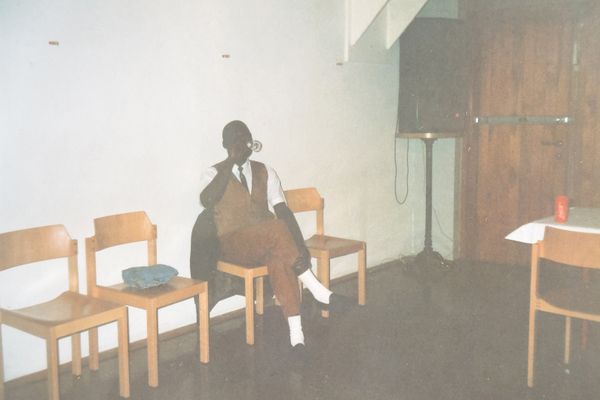

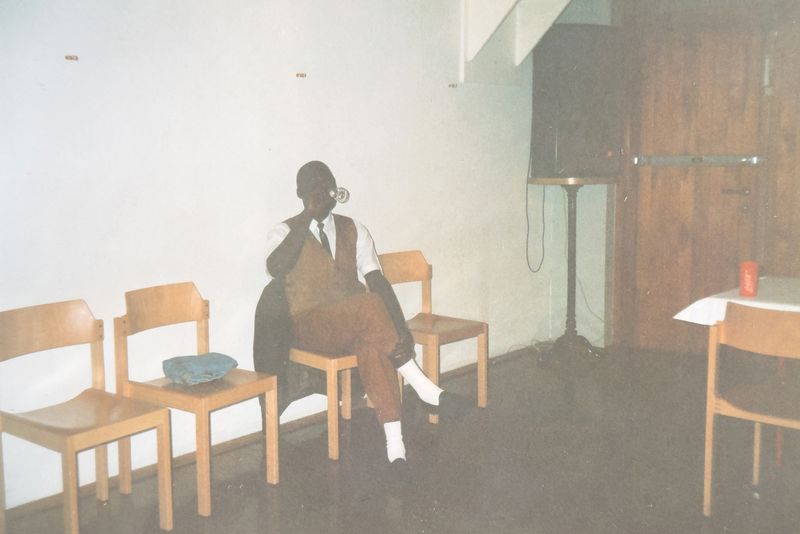

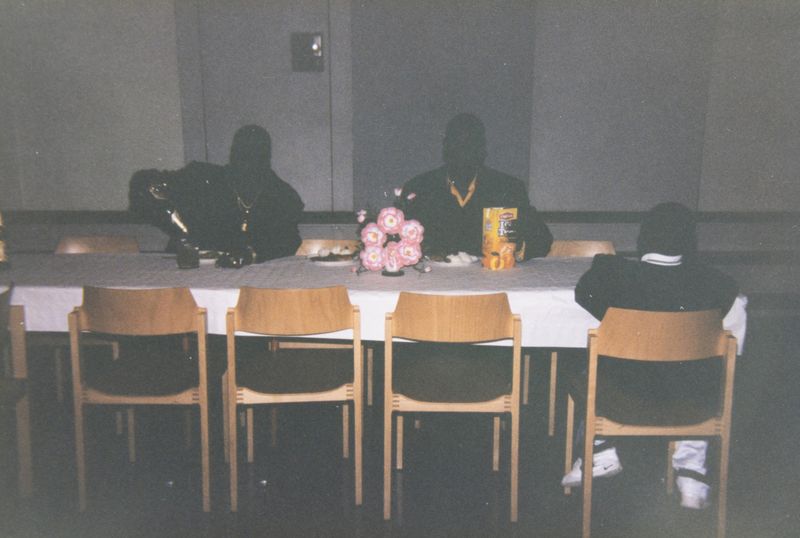

The third approach is more performative and deeply personal. Albano worked with her brother in so-called GDR everyday life museums, spaces that reconstruct domestic interiors using original furniture, curtains, and objects. These museums attempt to preserve how life once looked and felt, particularly for those who struggled to adapt after the sudden collapse of the GDR. Albano emphasizes that these spaces are not nostalgic in a simple sense; rather, they reveal how people lived, loved, and built families within a system that later vanished almost overnight, holding a difficult transition, a moment when “they just said on one day that the wall is dismantled from now on,” without a plan for how life should continue.

Entering these spaces with her brother becomes a crucial gesture for Albano. Afro-German histories, particularly those of contract workers, remain largely absent from official narratives of the GDR, despite the presence of contract workers from countries such as Angola, Vietnam, Cuba, Mozambique.

“I chose to go there with my brother because we haven't seen a lot of the Afro German side on this history,” Albano says. “We couldn’t see them in the noted history or what was really written.”

Her father’s story—arriving from Angola as a contract worker during a pause in the civil war—becomes a central thread, connecting global politics, migration, and intimate family life.

Much of what has been written from Afro-German perspectives is marked by loss. Albano’s work does not deny that history, but it resists being defined by it. She offers another point of view—one shaped by growing up “with an Afro German father and in an Afro German family.” The photographs with her brother do not illustrate history; they also intervene in it, asking whether something has been forgotten, and whether the past might still be rethought.

Absence is a persistent element throughout the project. Albano speaks of the impossibility of fully reconstructing the past, of searching through archives and conversations. What remains is a gap—between personal memory, institutional history, and what was never recorded at all. The collages hold this gap open, refusing completion.

Furniture extends this inquiry beyond the image. Real household objects—tables, windows, surfaces—enter the exhibition carrying their own histories. These objects cannot be separated from the lives they once held. Slightly altered, they shift perception without losing their identity.

Even the photographic process itself becomes part of the narrative. The use of a GDR-era camera and film points to the technological biases embedded in image-making. Older film materials were not designed to capture darker skin tones accurately, leaving faces partially obscured and underexposed. This limitation echoes the broader condition of invisibility that runs through the work—what was present, but never fully seen.

In the end, the project does not attempt to resolve the contradictions it reveals. Instead, it insists on their visibility, asking viewers to sit with complexity, loss, and transformation. Ultimately, her work is less about locating herself at the end of two cultures than about imagining how new cultural meanings can emerge from what remains.

“You never can see the whole picture or nearly cannot see the whole picture because every time something is hidden,” Albano says. “And this is all exactly how I felt while grabbing through this history.”

--------------

All photos © Verdiana Albano’s work, from the series I Ain't From No East Coast.

--------------

Verdiana Albano is a German-Angolan artist based in Frankfurt and Berlin. Her work is part of the Art Collection Deutsche Börse and has been shown internationally (f.e.Arles, Chongqing & Switzerland). Find her work on PhMuseum.

Lucia De Stefani is a writer and editor focusing on photography, illustration, and everything teens. She lives between New York and Italy. Find her on Instagram.