The Living Ancestral Echoes Of Irene Antonia Diana Reece’s Family And Memory

-

Published3 Feb 2026

-

Author

Through family archives, lineage, and layered imagery, Reece turns grief, love, and remembrance into a quiet form of activism, exploring what it means to see and be seen.

For photographer Irene Antonia Diana Reece, her project Don't Cry For Me When I'm Gone began as a response to a sense of displacement.

While attending graduate school in Paris, she found herself unable to settle into the city or its cultural rhythms. “It’s very iconic,” Reece, who’s from Texas, recalls. “But it’s completely different from the South in America, and I couldn’t make work.”

The distance was not only geographic. As France moved through a period of political tension, Reece was also confronting discrimination, a quiet but persistent pressure that deepened her sense of estrangement. Homesick and creatively stalled, she turned inward, returning to her family archives in an effort to re-root both her life and her practice.

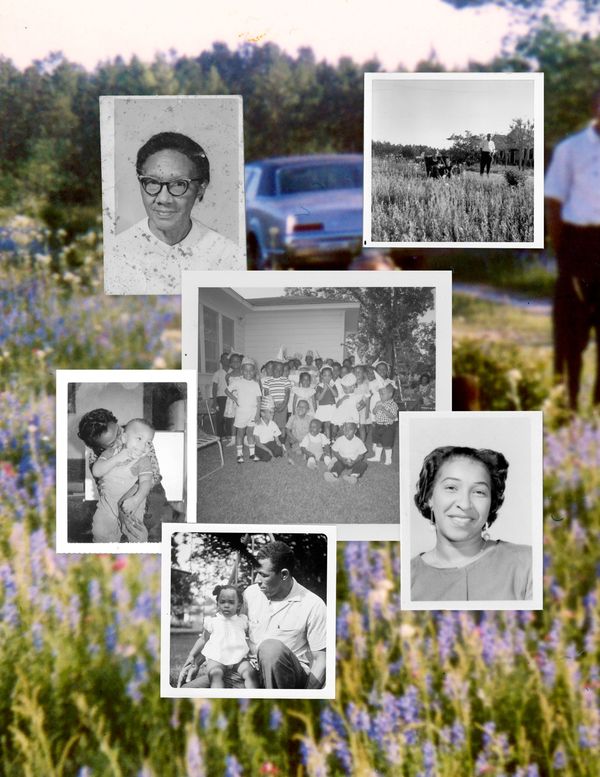

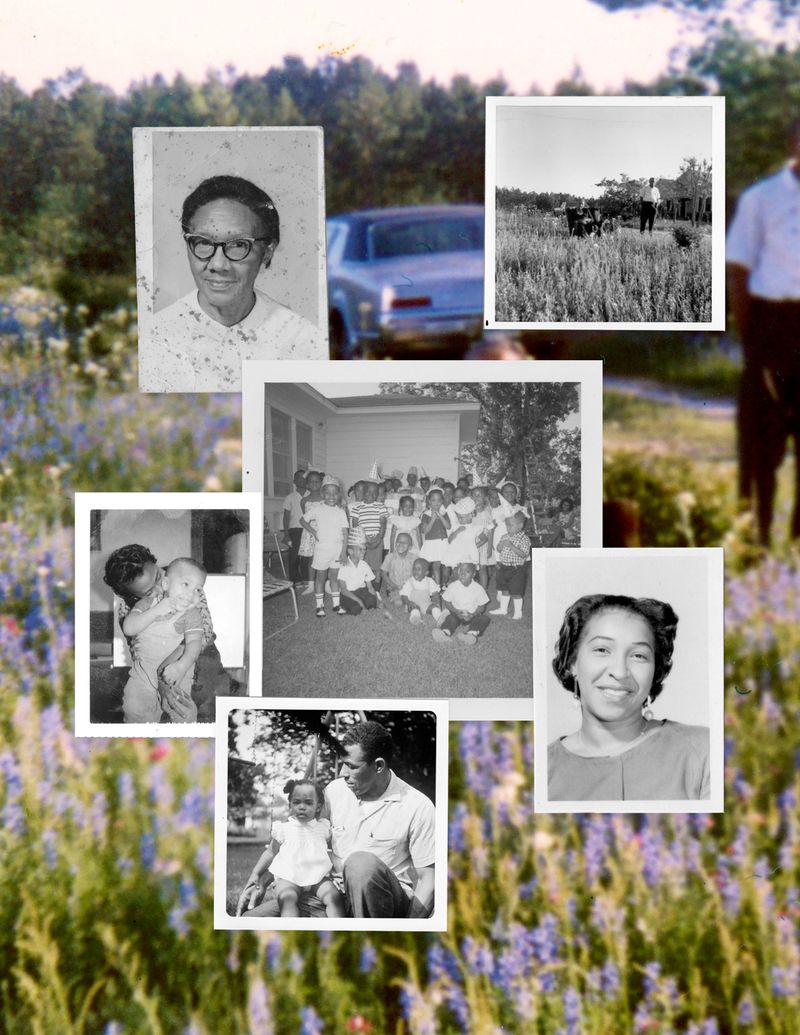

What began as an intuitive gesture soon became a decisive turn toward a more deeply personal approach. Working through photographs from her grandmother’s collection, Reece came to see the archive not as a static repository of the past, but as a living space for memory, inquiry, and resistance.

That resistance also emerged in how her work was received. When showing images from her father’s childhood—photographs taken during the 1960s, the era of segregation—she was often met with disbelief. The scenes, depicting moments of joy, care, and everyday life, unsettled narrow assumptions about what Black imagery is supposed to be. “They’d never seen this type of imagery,” she says. “So I just continued making that work and discussing those topics.”

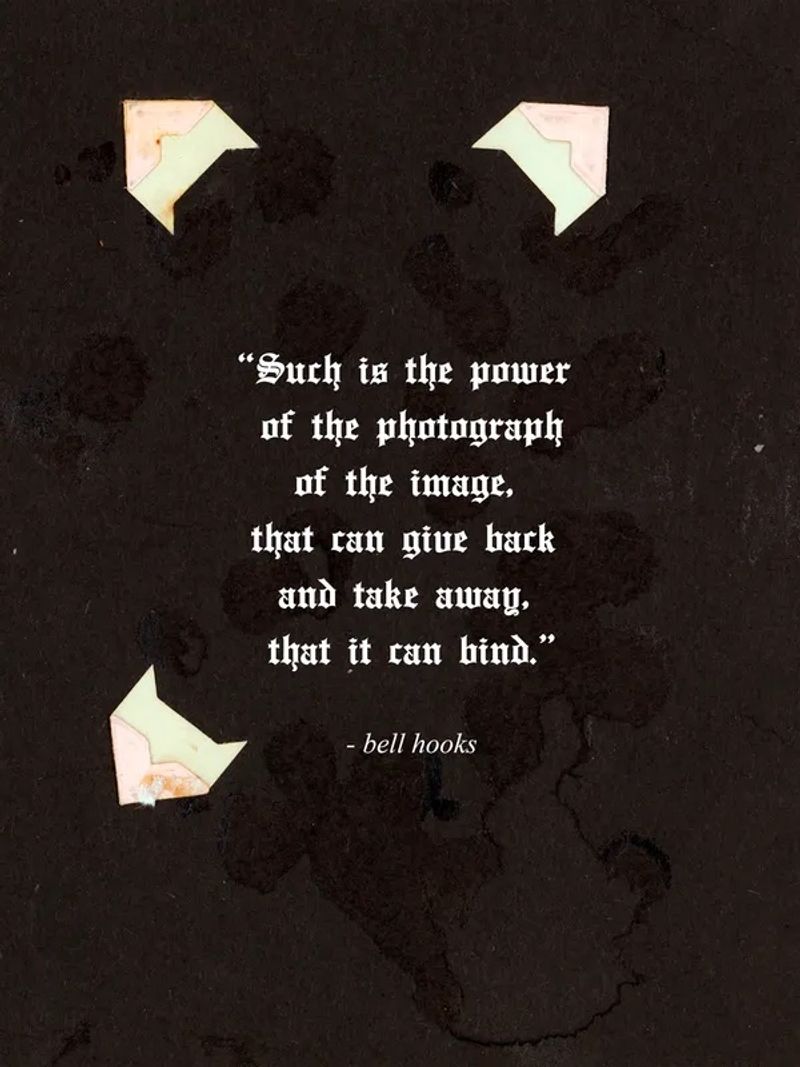

For Reece, working with family archives became a form of quiet activism. By placing images of love, resilience, and complexity at the center of her practice, she resisted what she describes as the pressure placed on Black artists to produce “oppression art”—work that renders struggle only in its most explicit forms. “There are different ways visually you can protest,” she says. “It doesn’t have to be so literal.”

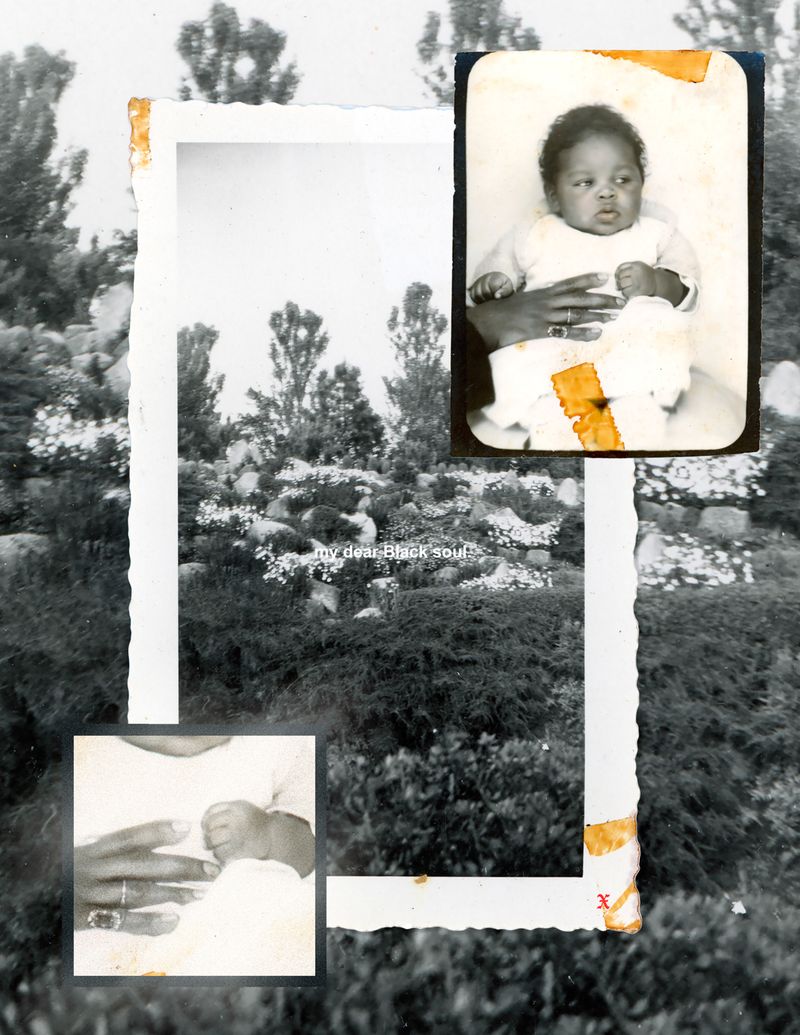

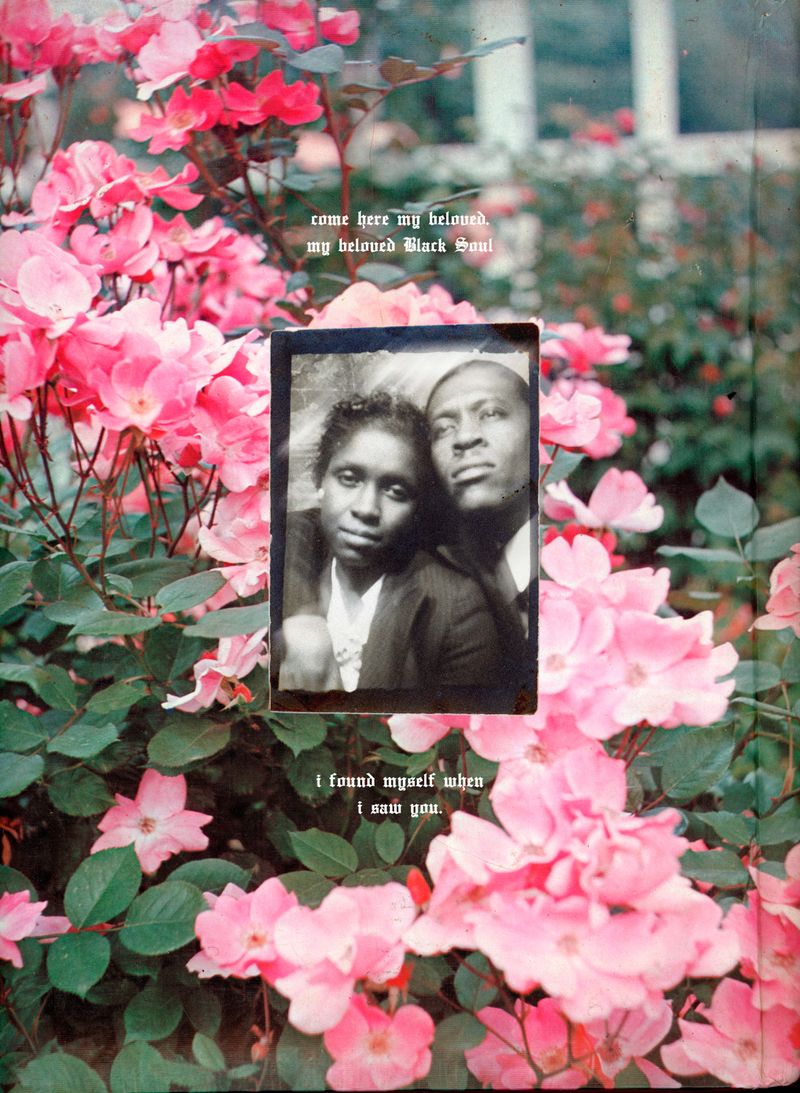

That resistance begins at the level of feeling. The selection of images is guided as much by emotion as by intention, drawing primarily from two family archives: those of her grandfather, who died when she was nine, and her great-aunt, a central figure in her childhood. “When you lose someone, that feeling doesn’t go away,” Reece says. “You’ll continue to have memories of them. They’ll come and go. And that’s what I was expressing.” As someone who is both Black and Mexican, she situates grief within cultural traditions that hold space for both mourning and remembrance. “In both cultures,” she says, “when someone has passed, you grieve them—but you’re also meant to celebrate them, to remember the good moments.”

Preservation itself becomes an act of care. Bringing these images back into view is a way of honoring the people they depict—allowing them to continue to live, to be seen. In one photograph, the camera frames only the back of her own head—a quiet gesture of lineage. The image shows framed portraits of her two great-grandmothers and her great-aunt entwined in her hair, and is meant to honor the people she was named after. She carries three names—those of the women who came before her—binding past and present through the act of looking.

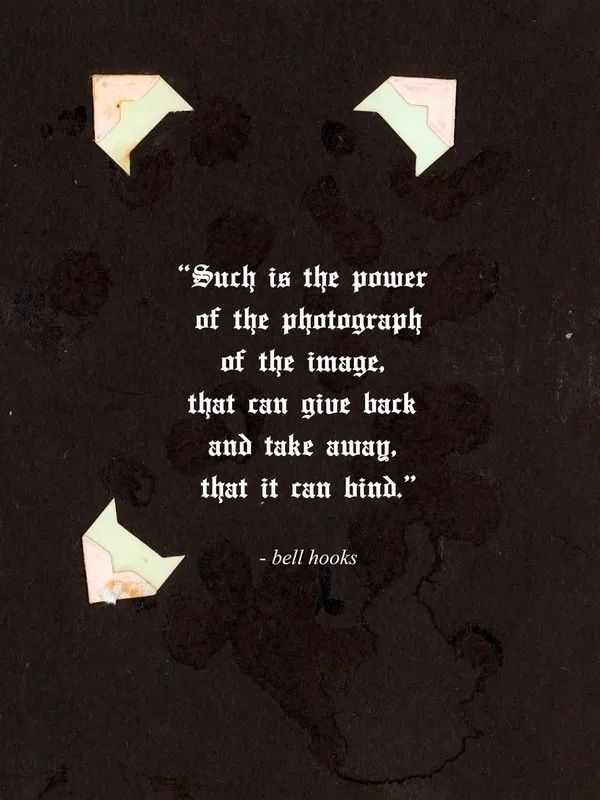

Text plays an equally important role in her work. Influenced by her father, a writer, Reece often turns to language to give shape to the emotions attached to specific moments of photographing. This dialogue between image and text carries into her installations, where words may appear on the floor or sit alongside photographs, expanding their emotional register.

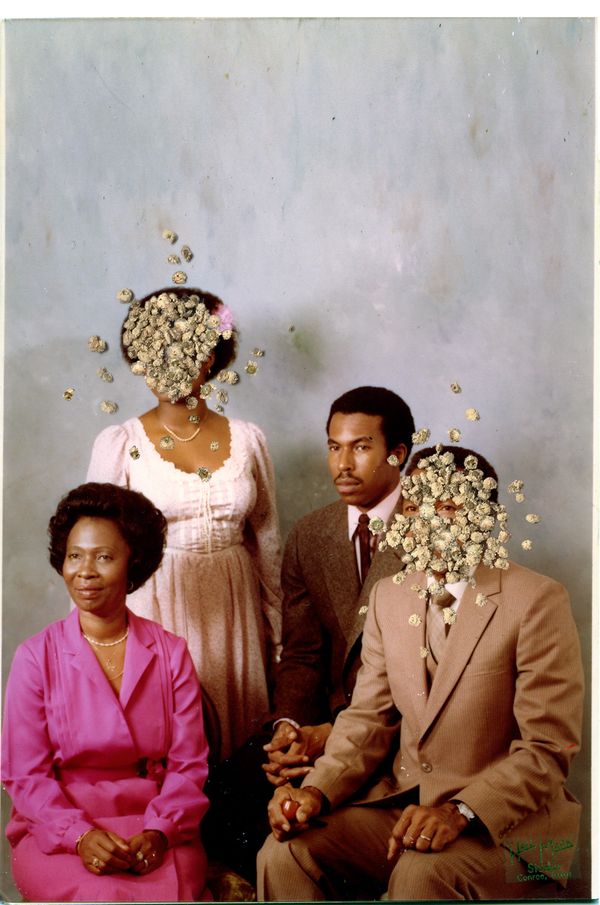

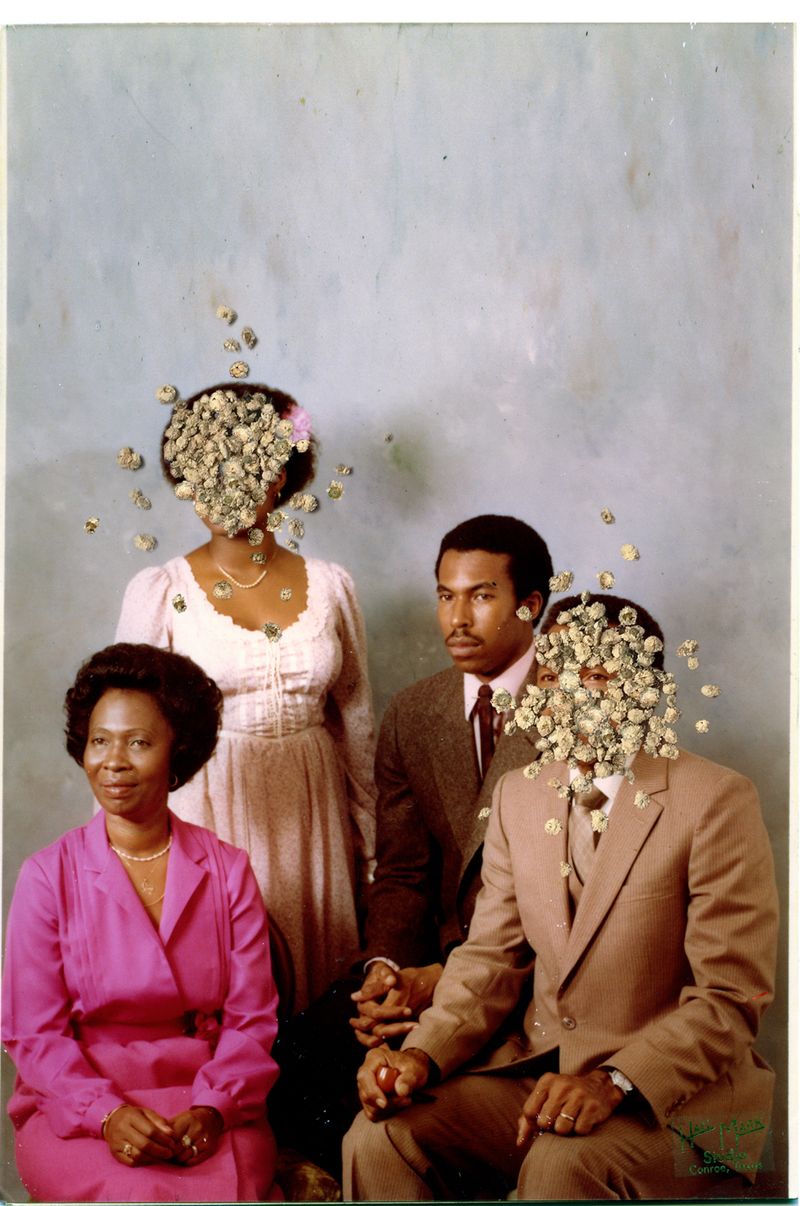

Recurring visual motifs also carry layered meaning. Flowers, for instance, appear through the work, often covering the faces of those who have passed—an act Reece describes as both mourning and love. In one image, however, her grandfather’s eyes remain uncovered. “I feel like he’s always watching me,” she says, “because I was so close to him.”

This sense of presence extends into other works, including one photograph in which Reece is seen from behind, walking through her home’s garden while carrying a framed portrait of her grandfather. She describes the act as almost performative: “It’s like your family members are visiting you. I just grabbed the picture of my granddad and photographed myself as if he’s coming with me wherever I was going.” The image, which she calls I’m Always With You, Prelude, evokes the sense that he—and her great-aunt—are always present.

Foliage and greenery, drawn from her upbringing on her family’s farms in Conroe, Texas, often fill the frame. Her grandfather, an agricultural teacher, and her great-grandparents, who owned a sugar cane mill, instilled in her the belief that the land heals and protects—a philosophy she honors through the recurring presence of nature in her work.

Ultimately, Reece sees her project as unfinished by design—something that continues to grow alongside her. Images may be added, removed, or reinstalled years from now. The archive, like memory itself, remains fluid—alive, evolving, and deeply tied to lived experience.

--------------

All photos © Irene Antonia Diane Reece’s work, from the series Don't Cry For Me When I'm Gone.

--------------

Irene Antonia Diane Reece is an American contemporary artist and visual activist. Her work explores the African diaspora, social injustice, family histories, re-memory, and community health. Through her practice, Reece honors Black Southern heritage, preserves Black archives, and illuminates the complexities of Black identity. Find her work on PhMuseum.

Lucia De Stefani is a writer and editor focusing on photography, illustration, and everything teens. She lives between New York and Italy. Find her on Instagram.