We Didn't Choose To Be Born Here

-

Dates2019 - Ongoing

-

Author

- Locations Johannesburg, Cape Town, Gaborone, Robben Island

-

Recognition

-

Recognition

This body of work is an exploration of Botswana and South Africa’s socio-political fabric through a personal lens. Blending staged portraiture, documentary images and re-enactments, I weave personal family stories with national history.

In 1958, my grandfather, Hippolytus Mothopeng, fled South Africa to escape racist Apartheid law. He went to Botswana, a far more peaceful country under British protection that eventually achieved independence in 1966. He worked as a town clerk in Francistown and Gaborone and as a hobbyist jazz musician.

In contrast, my grandfather’s uncle, Zephaniah Mothopeng, a teacher by profession, became an activist and joined the Pan-African Congress of Azania (PAC), eventually becoming the president of this political party. As a prominent leader of the struggle against Apartheid, my great-uncle Zephania Mothopeng served two separate jail sentences on Robben Island – the latter in 1979 for threatening to overthrow the government, for which he was sentenced to 15 years.

The title of my project, “We Didn’t Choose to be Born Here”, is a phrase explored in the minds of different family members during crises, separation, and ennui. In my photobook, I also write about my own experiences with activism during the #FeesMustFall protests that took place at the University of Cape Town in 2016, fighting for free, decolonized education across all South African universities.

My project focuses on the dilemma of personal responsibility in times of crisis. As an individual, do you fight for something greater for yourself in a collective struggle, or do you try to achieve the best for yourself? Furthermore, how does one deal with the reality of the world and the personal circumstances they were born into? How does one’s social class influence one’s ideology and aspirations? I use my family as a conduit to unpack these questions in my book project.

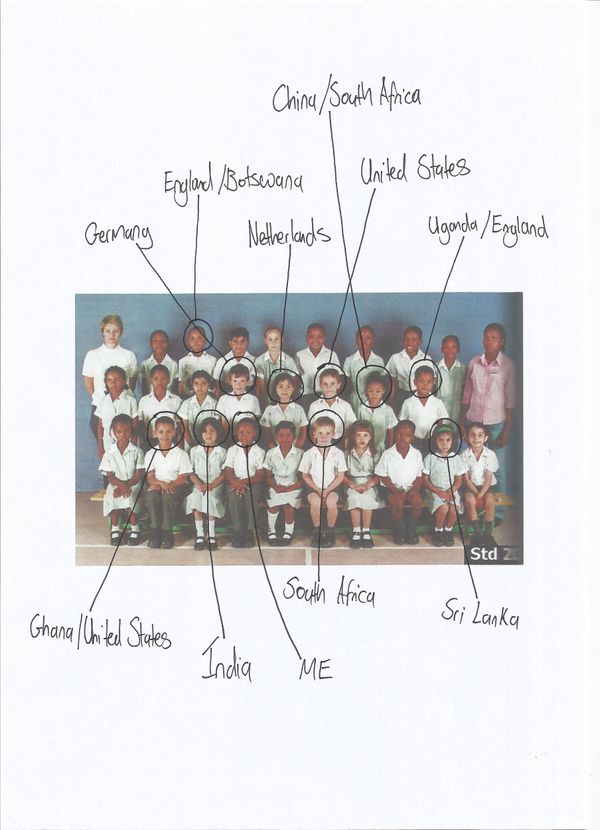

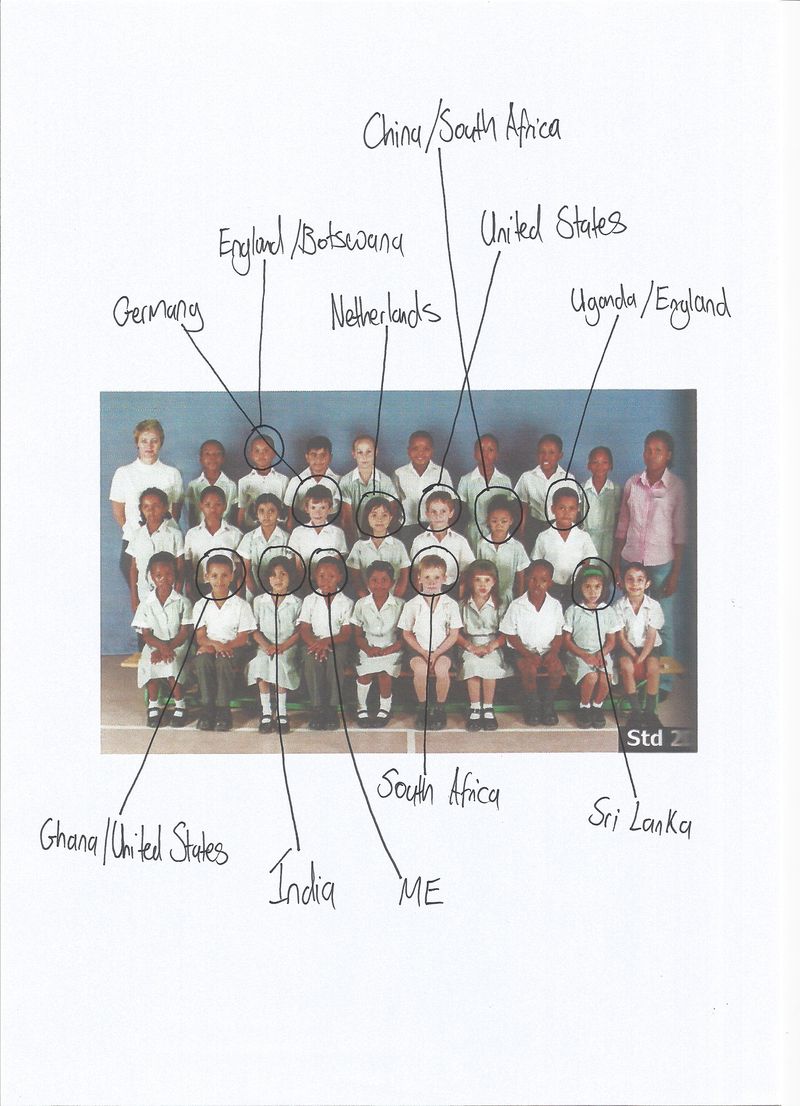

Whilst my grandfather had chosen to live in Gaborone as a civilian and lead a middle-class life, the consequence for his children was that they grew up with a strong cultural identity and family ties in Botswana and were often teased for being foreigners. On the other hand, Zephania Mothopeng’s children grew up without a father because the Apartheid South African state frequently incarcerated and tortured him for his underground resistance efforts.

My photographic work is collaborative with my family as they share their experiences, stories and memories, and I interpret them as an artist. I do this by either retracing their steps and producing documentary or post-documentary photographs of the places they have been or creating staged re-enactments where different family members, including myself, perform as past family members. I also make portraits of family based on feelings and emotions I want to communicate, such as grief, anxiety and hopelessness. I approach this work not as a singular auteur but as a custodian.

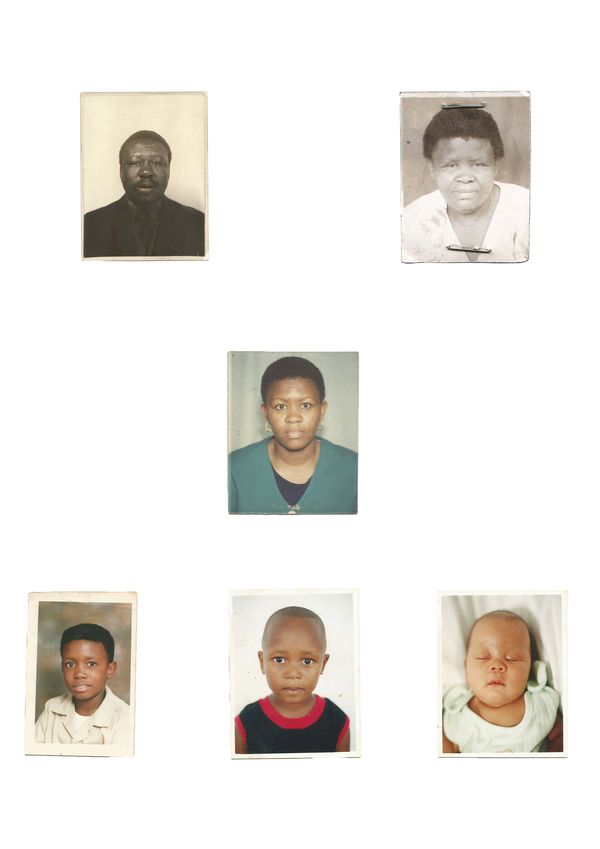

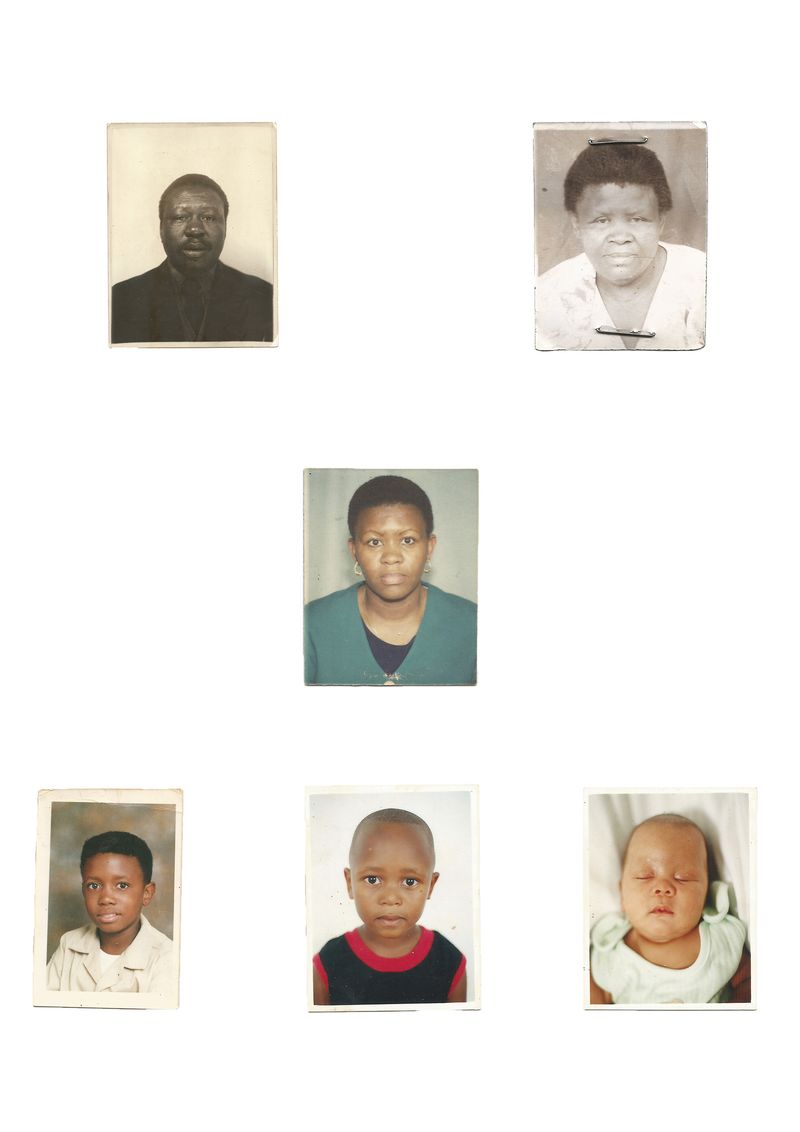

On the other hand, I also incorporate a variety of archival materials about my family, which contain both private (family photo albums, home movies, and documents) and public materials (documentaries, interviews, television dramas, and obituaries). The inclusion of this material is not only to add realism to my staged imagery but also to enhance my personal story. A crux of the narrative is that I only discovered the history of radical politics in 2008 after Googling my mother’s maiden surname for the first time and seeing Zephania Mothopeng. Because I had a privileged and sheltered upbringing in a small town, I had no incentive growing up to be involved in politics, activism, or to concern myself with goals outside of my own until I encountered a protester wearing a screenprinted t-shirt of my great-uncle Zephania Mothopeng during #FeesMustFall protests 2016 at the University of Cape Town.

Visually, my mother, Pinkie, is the most represented person in this ongoing photographic project, having lived the entirety of this 60-year history. Throughout this body of work, my mother ages from a baby to a teenager, then to an adult, and finally to a mother and caregiver for her mother. In contrast, my mother’s counterpart is Zephania Mothopeng’s only daughter, Sheila, who was the only person of the Mothopeng family to speak at the Truth and Reconciliation Commission in South Africa in 1997 at the end of Apartheid, where she outlined the trauma, she experienced as the daughter of a revolutionary and her wish that he had not had as prominent a role in the struggle for liberation as he did because of how it affected her family.

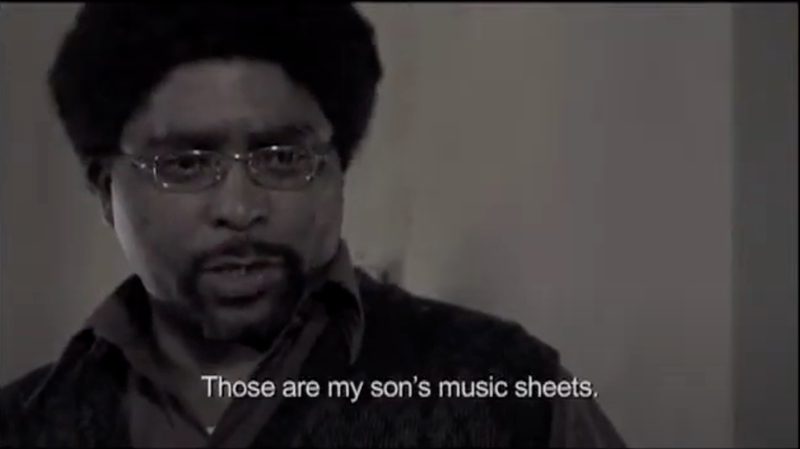

Amid the chaos and turmoil my family was experiencing, music was an anchor and provided an escape. My grandfather formed the first jazz bands in Botswana, the Metronome Swing Orchestra and the Scarers, who were comprised of fellow South African exiles. As there were no recording facilities in Botswana at the time, they only played live music, and the only archive I have of their performances is in photographs. On the other hand, my grandfather’s cousin and Zephania Mothopeng’s son, John, was also a musician and band leader of two bands, Batsumi and Marumo. The former band’s self-titled album is considered a classic amongst jazz aficionados in South Africa.

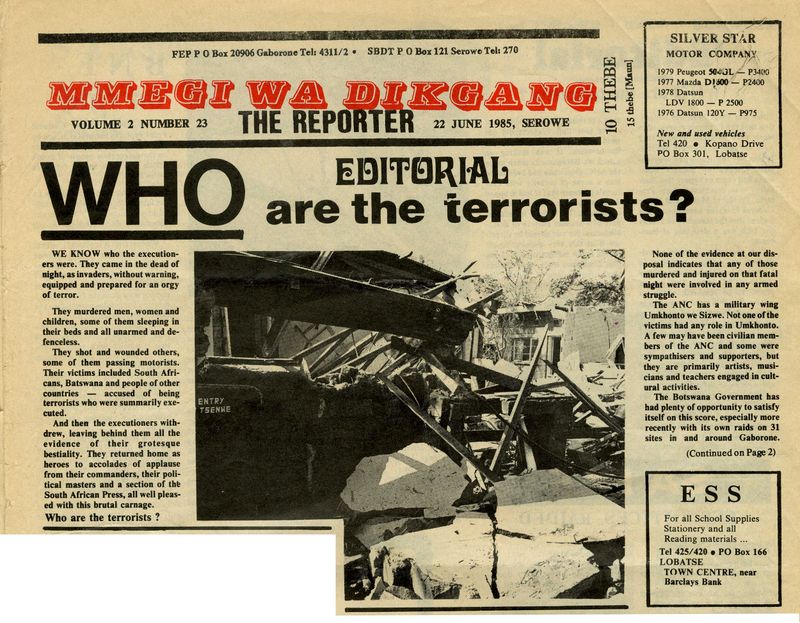

Another key event in history explored in my project includes the 1985 South African Defence Force (SADF) raid on Gaborone. On June 14th 1985, the SADF crossed into Botswana, violating International Law and attacked South African exiles living in Gaborone. The operation aimed to exterminate South African exiles aiding the armed struggle against Apartheid. There were twelve casualties. My grandparents, who had housed PAC soldiers in their home, survived this attack. In my photography, I have documented the homes that were raided by the SADF and also staged the night the raid occurred from the perspective of my mother and grandfather. Additionally, I have incorporated newspaper articles that covered the raid in local media.

However, despite the unrest, state imprisonment, identity crises and psychological trauma that my family endured for over half a century, my book ends on a note of hope and resilience. In an interview that Zephania’s wife, Urbania, gave in Paris, France, she says that “financially she is poor, but spiritually she is rich”. Urbania boldly states that if she were to do it all over again, she would still marry the same husband, have the same children and devote herself to the struggle against Apartheid. I include screenshots from this interview towards the end of the book.

Since 2020, I have been developing this photobook project independently in Gaborone, Botswana, where I am based. I would greatly benefit from the help of a curator or graphic designer who can collaborate with me to achieve a balanced and cohesive structure for my photobook, as it spans 60 years of history in Botswana and South Africa and represents many members of my family both visually and textually.

My project contains a vast array of archival materials, including newspaper articles, documentary footage, interviews, and family photographs. Given the vast amount of such material, I find it challenging to curate, and I need assistance in selecting the best design choices to convey my message and narrate effectively.