Vanities

-

Dates2025 - 2025

-

Author

- Locations Berlin, Cairo

-

Recognition

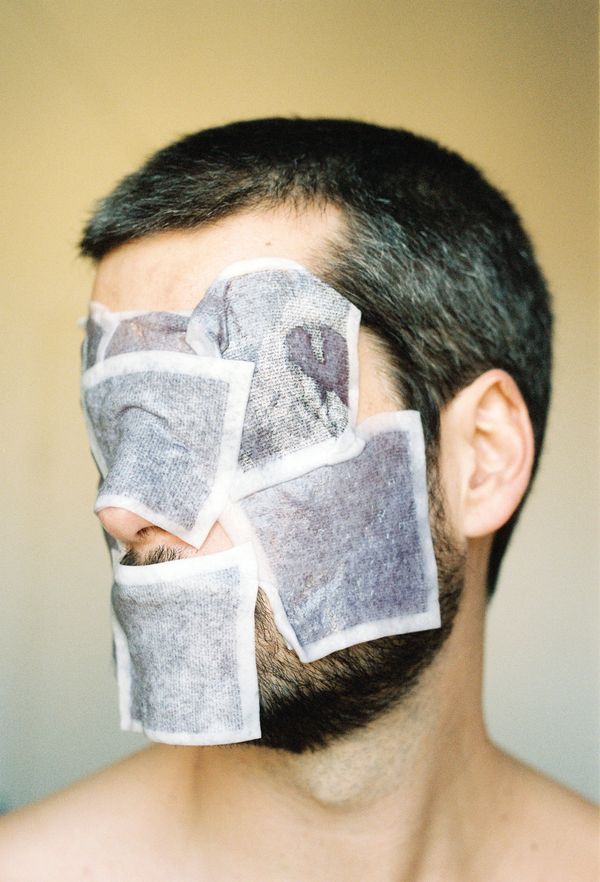

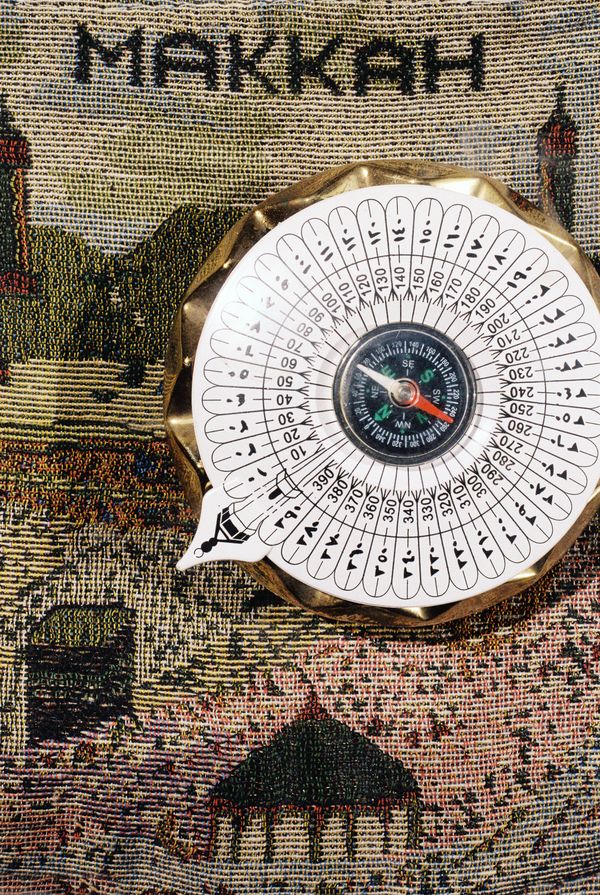

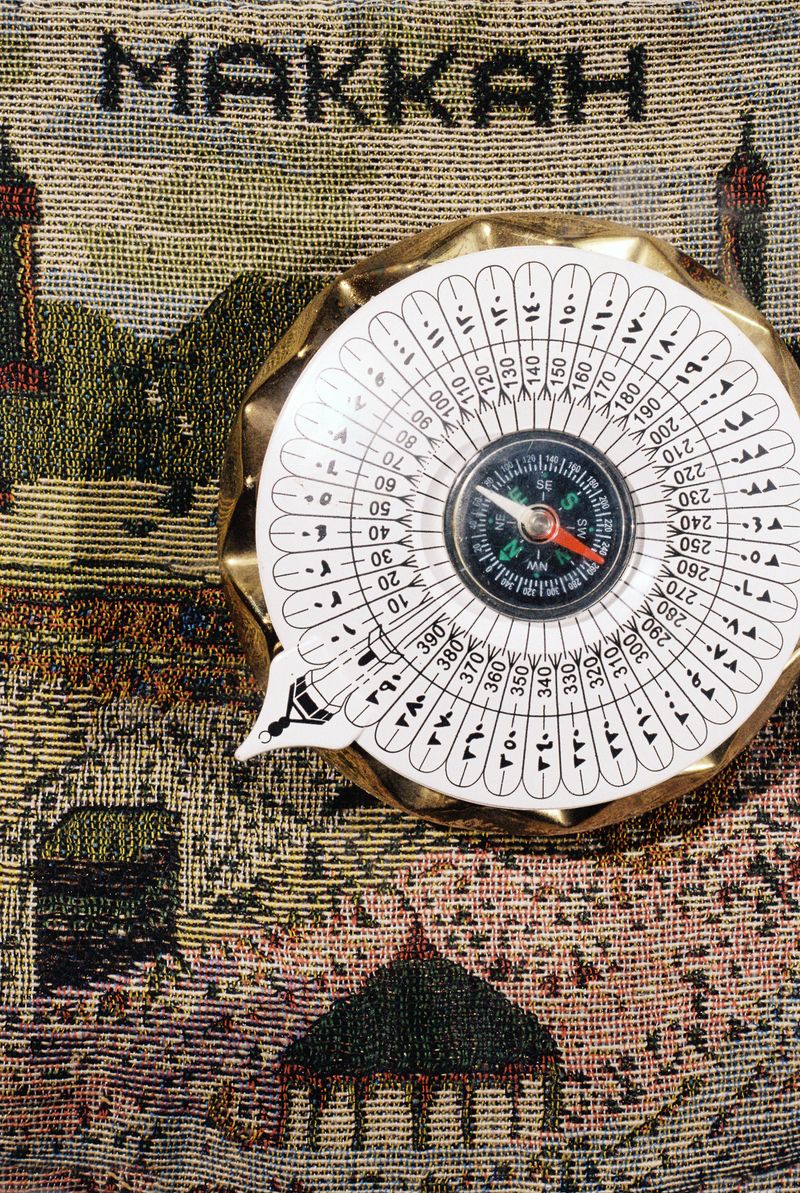

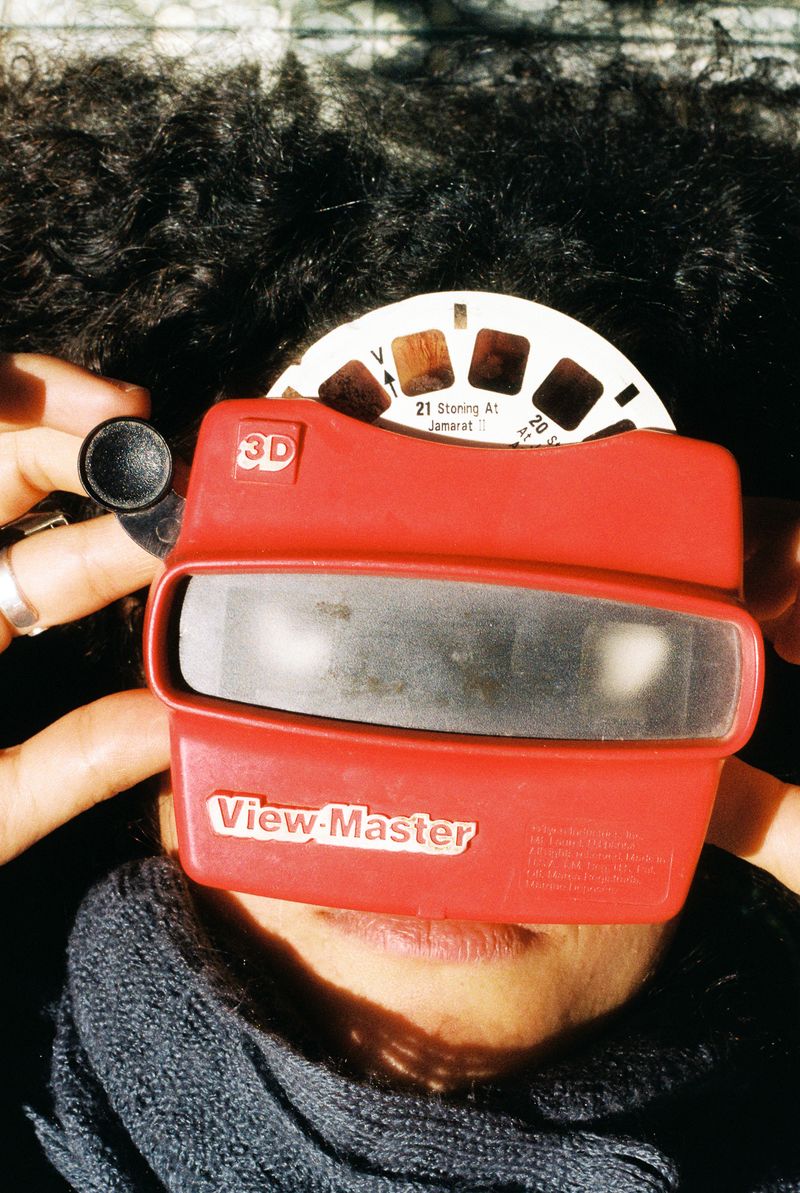

Through recontextualized religious products, Vanities explores the tension between faith and consumer culture, urging a reflection on the impact of capitalism on spiritual practices.

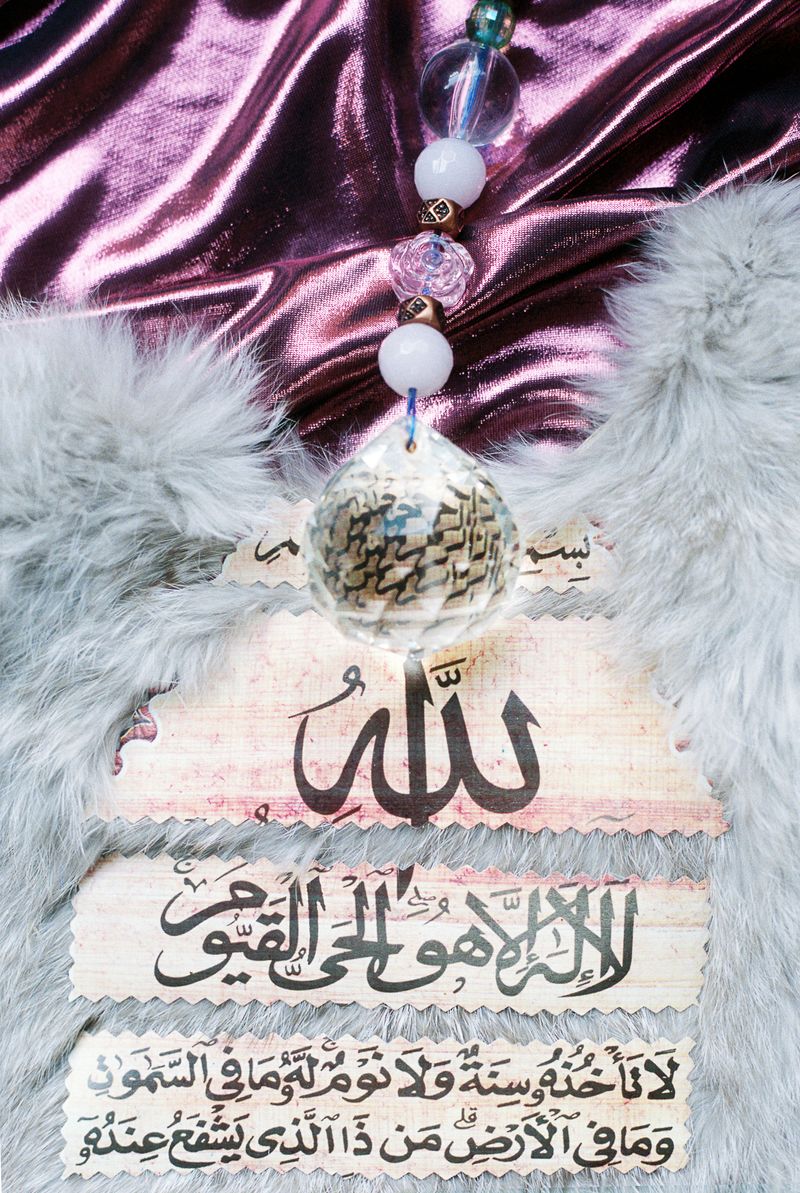

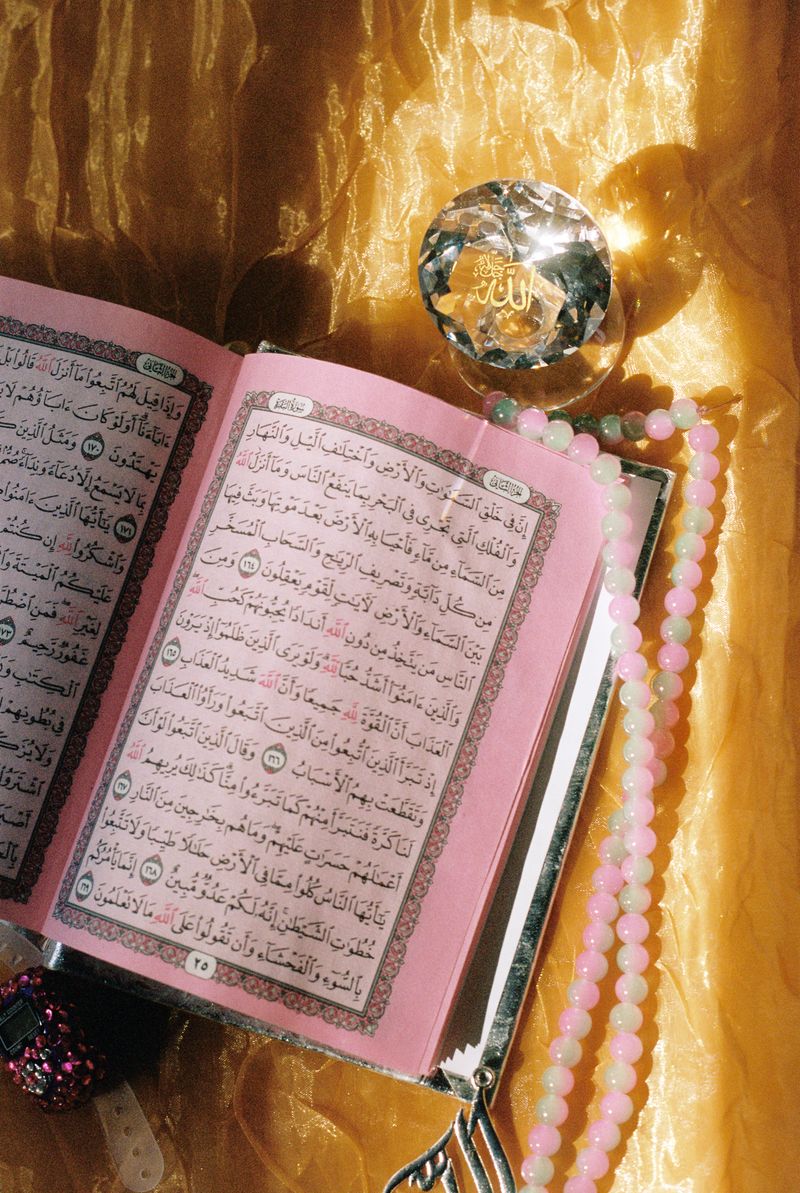

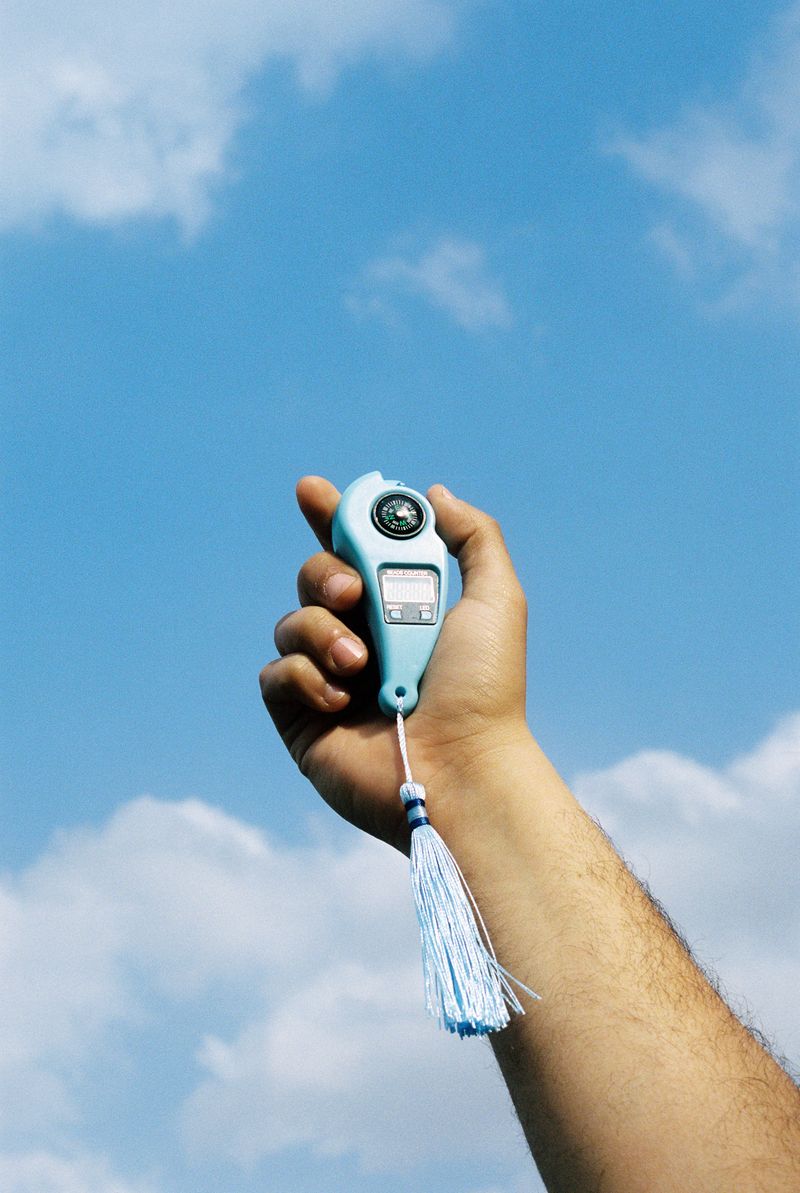

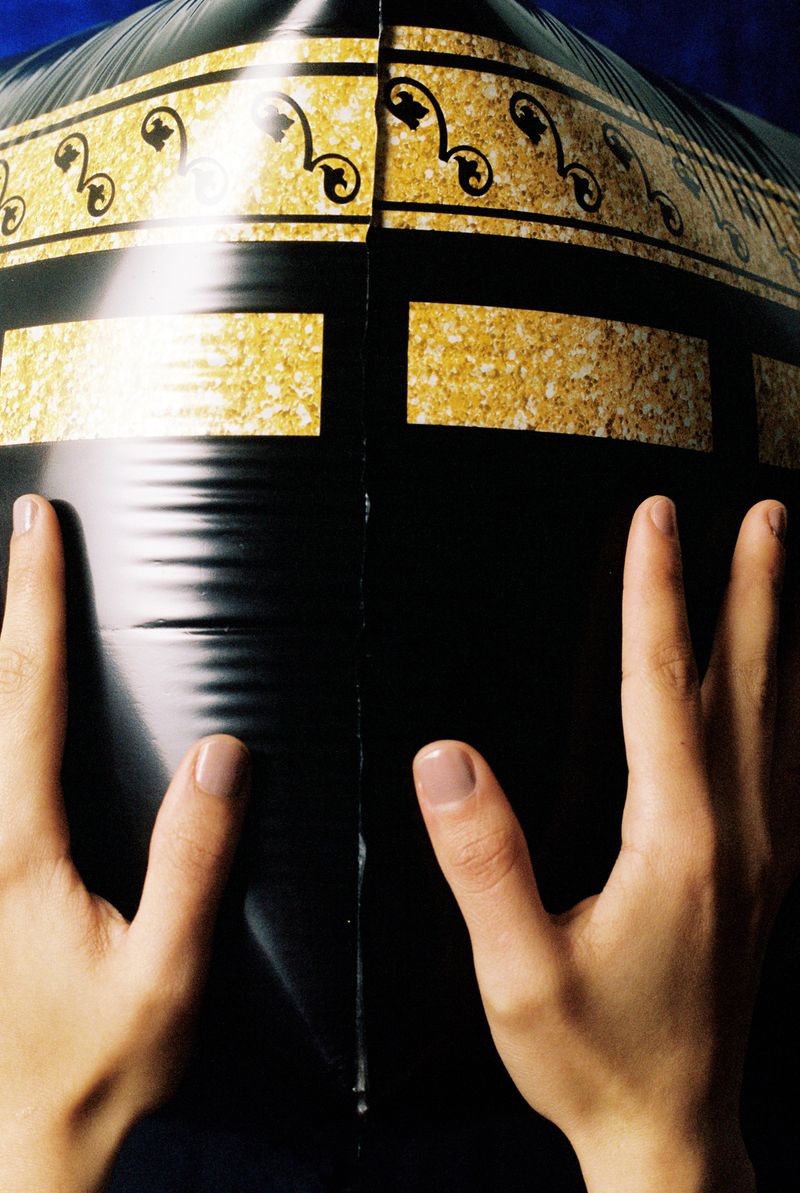

As I walked through Berlin, I stumbled upon a party decoration shop with a Kaaba balloon in its display window. I felt an urge to buy it, anticipating that sooner or later, someone would deem it blasphemous and it would disappear. But weeks passed, and it remained. Eventually, I bought one, unsure of its fate, only to discover, amidst Christmas ornaments, New Year’s streamers, Halloween props, and Valentine’s hearts, that there was an entire aisle dedicated to "Muslim" decorations. I had to suppress my laughter, but something about it felt unsettling. It wasn’t that I was unfamiliar with these traditions. I had grown up religious, I used to be a practicing Muslim. Yet, something about encountering a Ramadan advent calendar in a Berlin grocery store struck me with the same eerie feeling. Islam was being repackaged, commercialized, turned into yet another seasonal trend. It had become a market, another lucrative demographic to tap into. Curious, I began looking for other “religious” products on the market. My algorithm quickly caught on, feeding me endless suggestions, hundreds of Pinterest posts advertising "Muslimah Essentials”, among them: matcha lattes, pastel-colored Qurans, and bejeweled digital rosaries (aka Zikr Rings). Islam had become an aesthetic, faith was being sold in shades of pink and gold, wrapped in glitter and packaged for consumption.

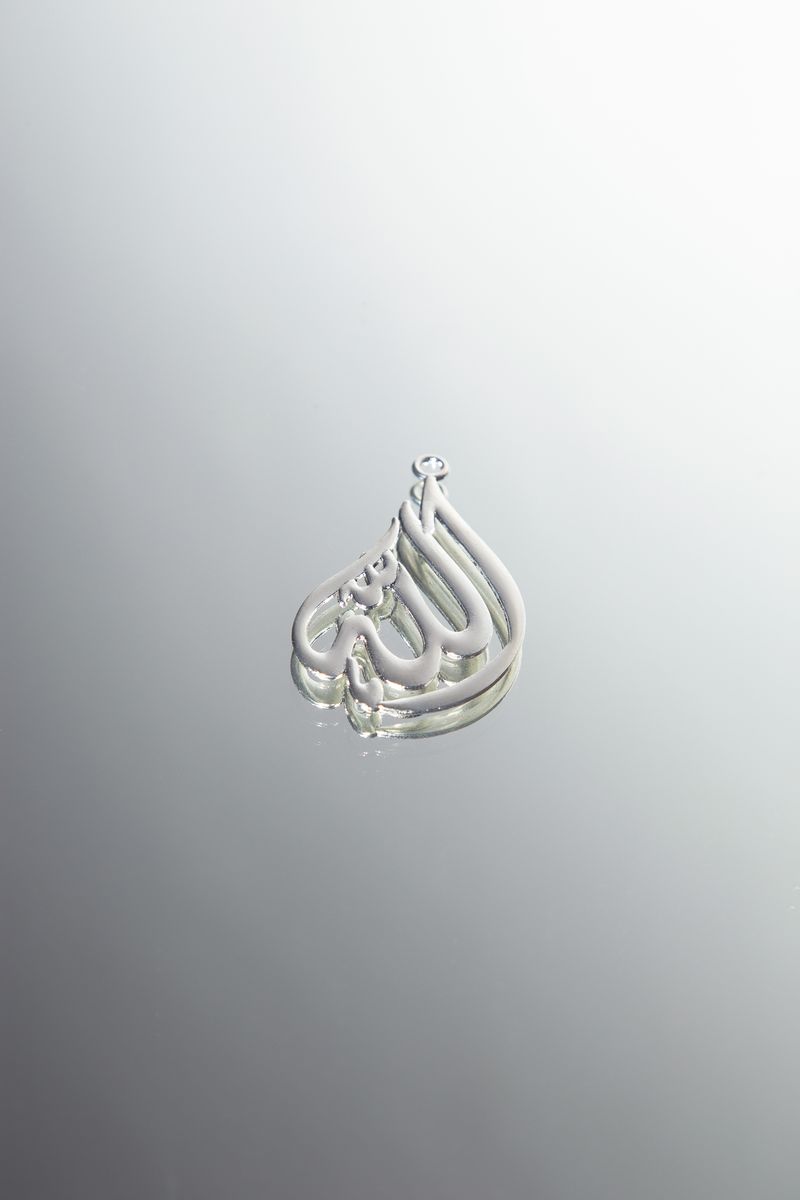

No one truly needs a Kaaba chocolate assortment box, a Quran and Zikr Ring matching gift set, Zamzam water-infused eyeliner, or "Ruqyah Paper" to ward off magic or the evil eye. When did we allow capitalism to monopolize spirituality? When did our individualistic desires infiltrate our religious practices? Islam, at its core, emphasizes humility and detachment from material excess, in the way we fast, in the way we give charity, in the way we are buried. So how has overconsumption, the very antithesis of these values, become so unquestioned?

I documented and recontextualized many (though not all) of these so-called "religious products" in an attempt to spark a conversation. One day, when I was buying an “Allah” necklace, the seller opened up and said it felt weird he was making profit out of the name of God. Vanities challenges viewers to reflect on the extent to which capitalism and consumer culture have infiltrated spiritual practices.