Time is a River

-

Dates2021 - Ongoing

-

Author

- Location Shahpur, India

-

Recognition

-

Recognition

The most frightening stage in any metamorphosis is when an obsolete form has eroded, but the new one is still a chaotic, pupal mess. Shahpur lies on that cusp. Shedding its past it faces a crisis of identity and loss.

“Time is a River” is an intimate essay about the passing of time.

In it, I use collages, photographs, and films to study how time has enacted itself upon Shahpur, my village in Uttar Pradesh. This metamorphosis is most visibly recorded (and emotionally felt) via four entities—my decaying ancestral home, the now-dwindling Sambar population in this belt, the shifting course of the Yamuna, and my memories of my deceased grandfather.

The most frightening stage in any metamorphosis is when an obsolete form has eroded, but the new one is still a chaotic, pupal mess. In many ways, Shahpur lies on that cusp. Shedding its past of riverine agriculture, a thriving ecology, and lasting caste hierarchies, it faces a crisis of identity and loss.

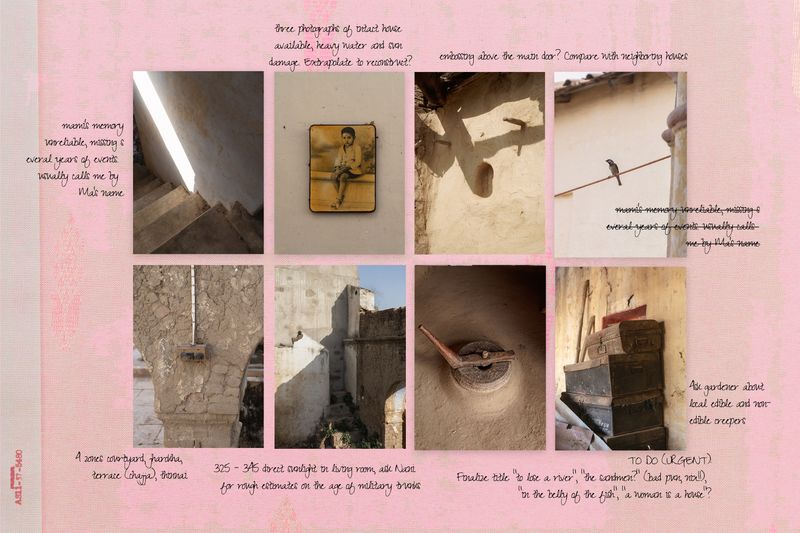

Part I: The Ancestral Home

How do two centuries of lived life vanish? Cracks grow into walls like tendrils, and bit by bit, as people leave a house, it also leaves them. My now crumbling nineteenth-century home in Shahpur stands devastated by rural outmigration, a phenomenon that affects countless social fabrics across the country. I first conceived of this project during a visit in 2020. Back then, as now, I was struck by how deserted it felt—a ghost town stood where there was once the legacy of elders and the promise of love.

My project highlights this emptiness by giving voice to the unspoken and unspeakable things that grief leaves in its wake.

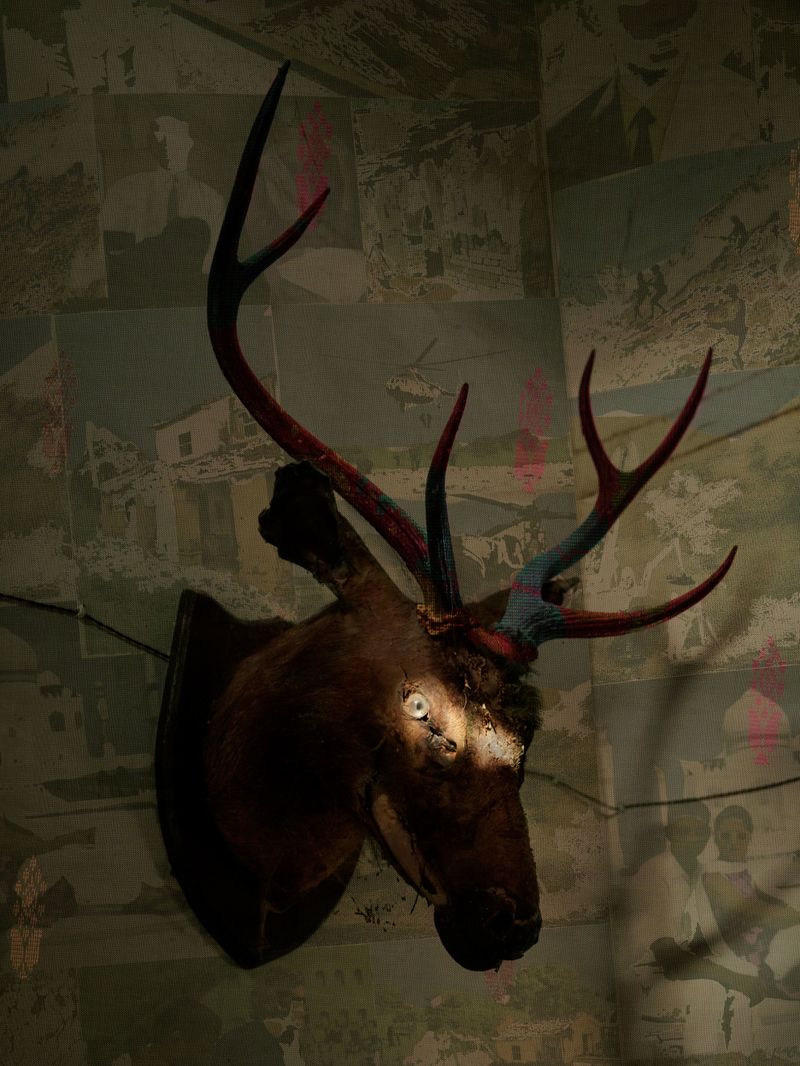

Part II: The Deer

It is not just humans who migrate, flee, desert, or die. The Sambar deer, a large and magnificent animal that once populated the [forests] around Shahpur, is now a rare sight. Victimized by rampant industrial development, it too has found that old haunts have become uninhabitable.

When we do find a glimpse of it, it is mounted on a wall. The taxidermied deer head is not only a vestige of human cruelty but also a symbol of destructive caste-based power. Since hunting was reserved for the upper-caste populations, an endangered deer was a rare and enviable trophy to collect.

Part III: The River

The Yamuna cuts through Shahpur like an artery. A rushing river that once watered crops, fed children, and provided coolness in an arid place is now shrinking back, whether in fear or revulsion. Villages like Shahpur is where toxic run-off gathers, where the heavy displacement of soil causes drastic changes in the landscape. These changes occur slowly—sometimes over centuries—but they do occur.

As generations change hands in the village, they will not inherit the same river. Instead, they get swathes of exposed riverbed where the underbelly of unchecked development shows itself. They must now grapple with the impossible task of finding new entry points to the Yamuna.

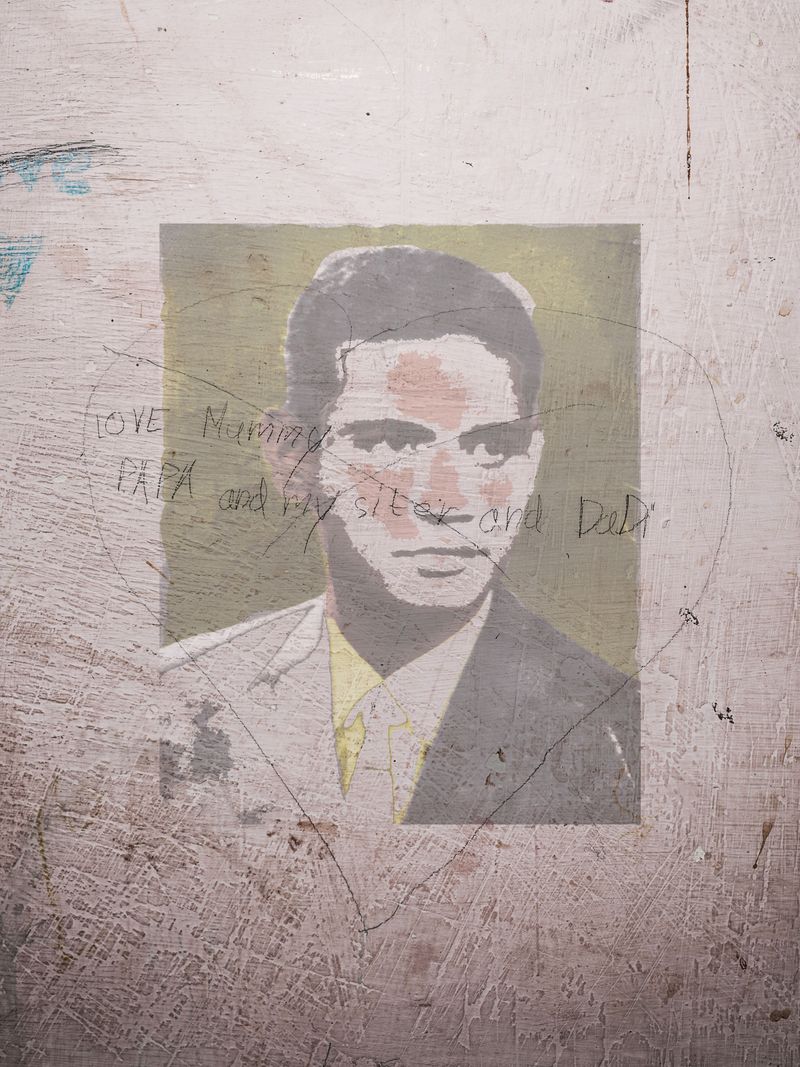

Part IV: Grandfather

At the center of this swirling mass of ideas is one figure, whose memory is becoming increasingly hazy. He anchors this project just as he once anchored our family, and the social structure that they were a part of. His legacy is questionable, militaristic, tinged with violence. However, the more I think about the violence of erasure, of an entire village’s history gradually bulldozed over, the more I believe that it is not our place to pass judgment. Instead, I hope my work can pave the way for a more nuanced, perceptive look at yet place abandoned to time and memory.

Approach:

Visual, mixed-media collages are at the heart of my narrative. The ability to layer together not only images but also materials allowed me to add texture and depth to a project that is rooted in complex human subjectivity. Apart from using images from family albums, I’ve also employed pieces of my grandmother’s clothes. In most family photos I collected over time, she is conspicuously absent. Adding traces of her fabrics is my way of incorporating her legacy, and more importantly, questioning the kind of self-evident representation that archives often rely on. If a woman lived a full life, but left no visual testament behind, was that life never lived? Patriarchy, urbanization, and ecological disaster—all three are united in the fact that they forcefully expel you from a place of rightful safety and joy.

This is a deeply personal project, like any project about metamorphosis should be. It is mediated through the distortions of grief, the conflicting legacy of my landowning progenitors, and the vast silence of lost and irrecoverable stories. By bringing these threads together through alternative printing processes, I’ve attempted to build a layered portrait of history, ecology, politics, and dynamic human life.