The Pregnant Tree

-

Dates2016 - Ongoing

-

Author

- Locations India, Tamil Nadu, Nilgiris

-

Recognition

-

Recognition

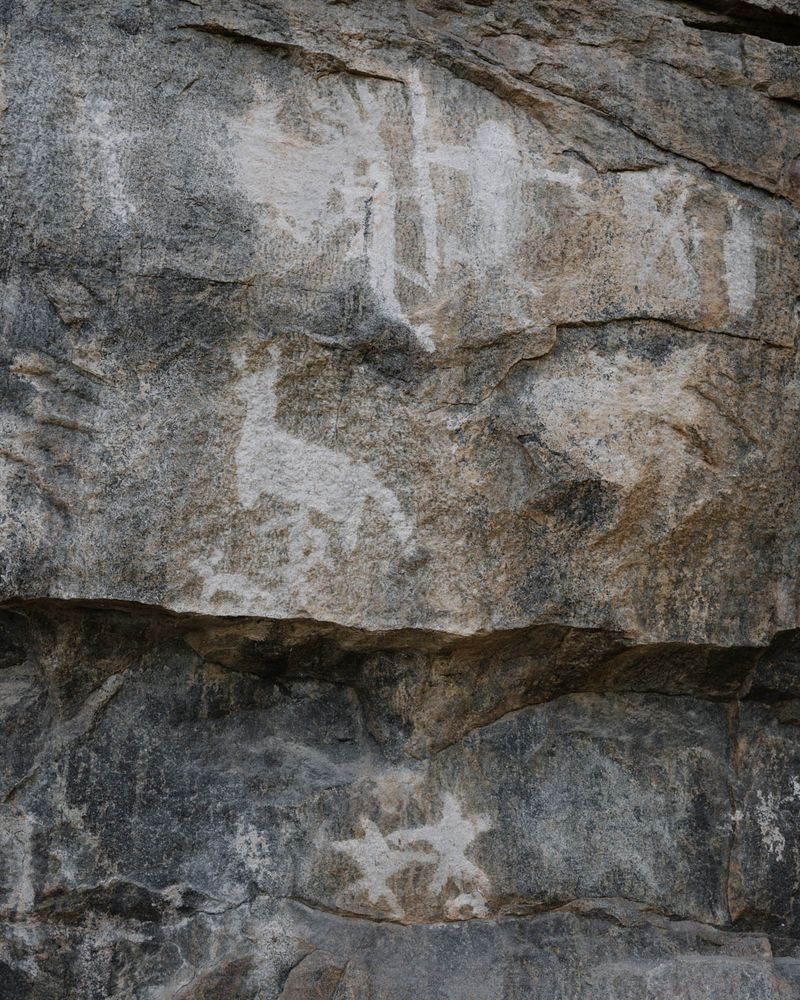

This work looks at the relationship between the Kurumbas and the landscape they belong to, through their mythology. Using their origin stories as a starting point, the work is a collaborative photographic imagining of the future of the forest.

Story-telling is like second breadth to the Kurumbas, who are an indigenous community from South India. They have stories about everything. Especially about the forest.

Sitting outside his house on the edge of a cliff, during one of my first visits to the region in 2016, Kumar, a Kurumba priest, told me about the land we were sitting on - the land his ancestors have called home for millennia. There are special parts of the forest here that are worshipped, which have been carefully protected, with no human having entered them for hundreds of years. These sacred groves are shrouded in folklore and in contrast to their surroundings, are still bursting with life. A minute into our conversation Kumar looked me straight in the eye and said “there’s fire everywhere now and the power in our forests is weakening. Things are no longer in balance.”

The shola (endemic) forests of the Nilgiri mountains in South India, to which the Kurumbas belong, are fast disappearing. Official records have measured a loss of 80% in the last 200 years. With this, entire villages have been pushed out of the forest diminishing their access to food, water, medicine, worship, livelihood and an entire way of life. There is also now, less time for telling stories. Like the shola, these are fast disappearing.

Over the past 8 years, I have been going back to different villages to try find these stories and have been allowed to listen to some. Stories that belong to the community and have been held for generations. Not all stories can be told at any time. Some are like prayers and can be heard only on sacred days or when the gathering has been properly prepared for the occasion.

Here, no story is absolute and it exists many-fold in every version of every telling.

These stories are powerful totems for who the Kurumba are. A way to remember and protect their place in the world.

In this project, I have played primarily with one story. Between 3 different villages with children and elders from Selarai, Sengalpupdur and Mettukkal. This version of the story belongs to Subbu. In each session we would start by sitting in a circle. Subbu’s voice would get lower, almost like it was getting closer to the ground and to us. And he would tell us the story of how the forest was born.

I have been given permission to bring this story outside the community, to share with you. So read carefully.

God makes the world and then gathers a group of birds because he has a task for them. He tells them “There are no trees in this world yet and we need forests so I am going to give you these little seeds that I need you to take back to the world and put into the soil.”

The birds take the little seeds and begin their journey back. But this entire conversation was heard by a naughty giant who decided to intervene because he really didn’t want any trees around. So he stops the birds and tells them ‘ you give me the seeds’ I’ll do this work’.

He takes the seeds from the birds and put them into a big hot pan and begins to roast the seeds so that they die. There’s this one very intelligent little birds called the piriki who realises that something not quite right is happening. She dives into the hot pan, saves some of the seeds. Some of her feathers burn and blacken as she does this but she carries the seeds in her beak and plants them in the land. These seeds turn into huge thriving forests.

The Kurumbas believe that forests are born from the work of birds. There is a little black and white bird called the pirikki that is found in the forest - this story explains how they got their marks.

The Pregnant Tree looks at the relationship between the Kurumbas and the landscape they belong to, through their oral folk stories. This work is essentially about the potency of story-telling. The way stories become like family and pass through people over many generations, how they are held and how they in turn protect a sense of place and community. The work weaves in and out of many of the tales I’ve heard here since 2016, as well as those that have been made up by children in the three villages I’ve been working in - about what the future of the forest could look like.