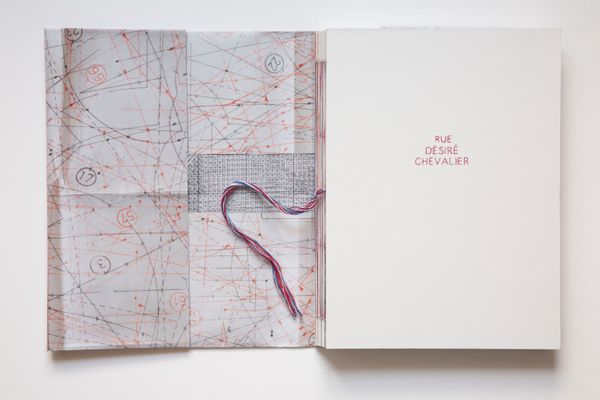

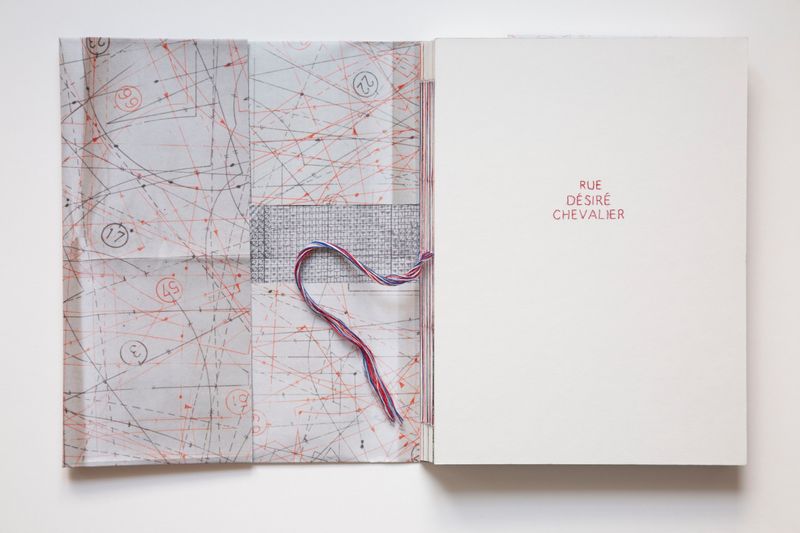

Rue Désiré Chevalier

-

Dates2017 - 2024

-

Author

- Location France, France

-

Recognition

Through fragmented memories, archival documents and my own photographs, I reinterprets my family's connection to a homeland to which they were never able to return, creating a narrative between past and present, home and exile.

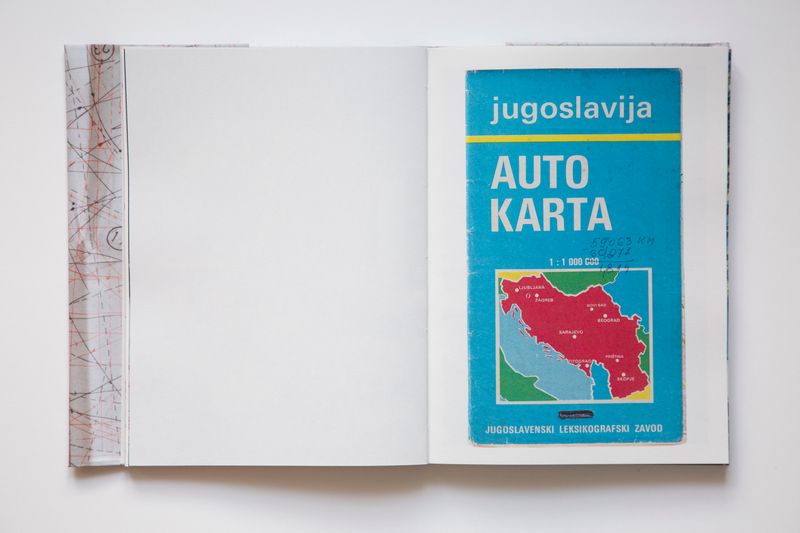

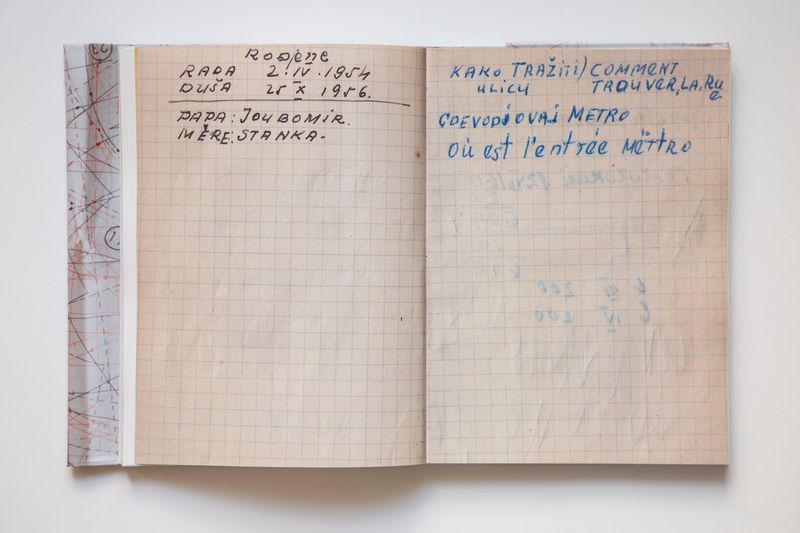

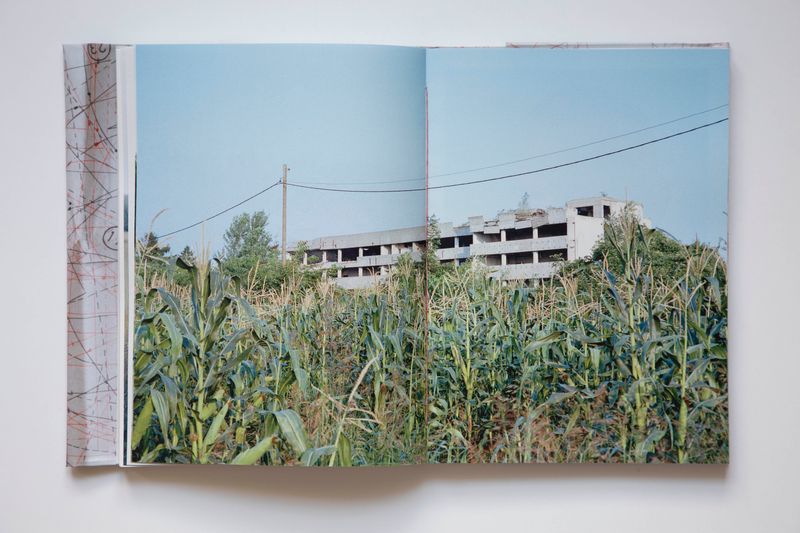

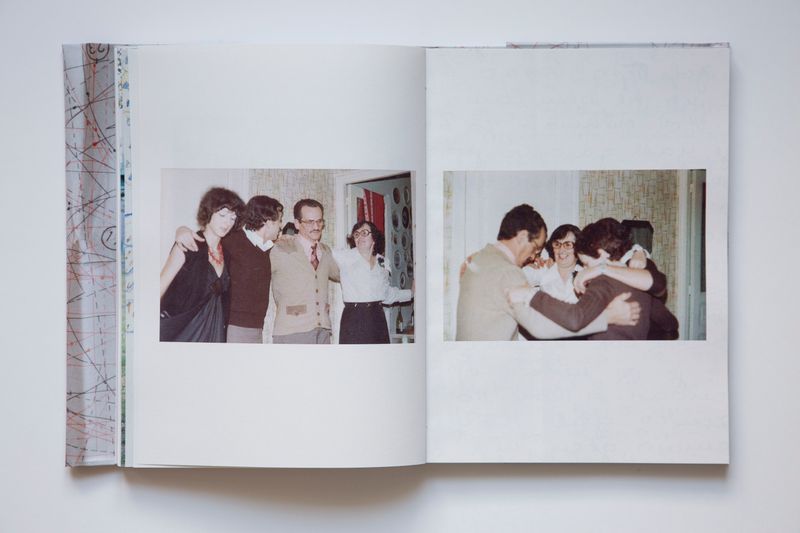

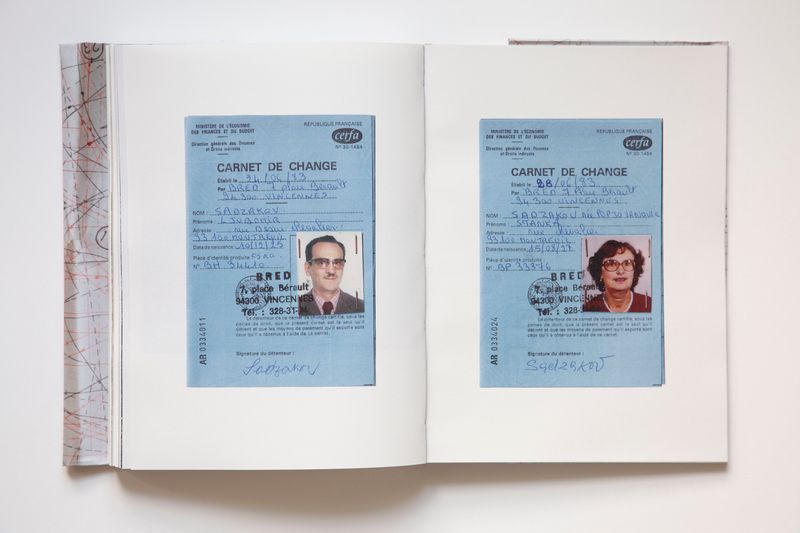

A new country, a new start and the trips back and forth of an entire lifetime. This sentence could sum up the journey my grandparents undertook in the sixties. In 1965, a bilateral agreement between France and the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia marked the opening of borders and the arrival of Yugoslavs in France, an exceptional event for a socialist country. Despite the historical links between the two countries, the contrast was huge. My mother, Dusanka, started primary school at age 7, and was renamed Daniele. My aunt Radmila had her name changed to Régine. If in theory, Yugoslav and French workers were equal, the reality was quite different. Désiré Chevalier is the street where they lived most of their lives. Every summer for the next forty-four years, they drove back to their hometown of Novi Sad.

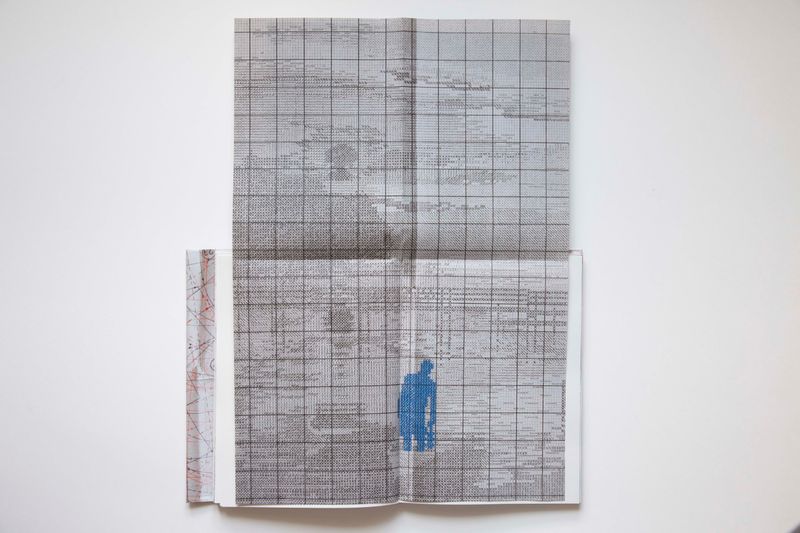

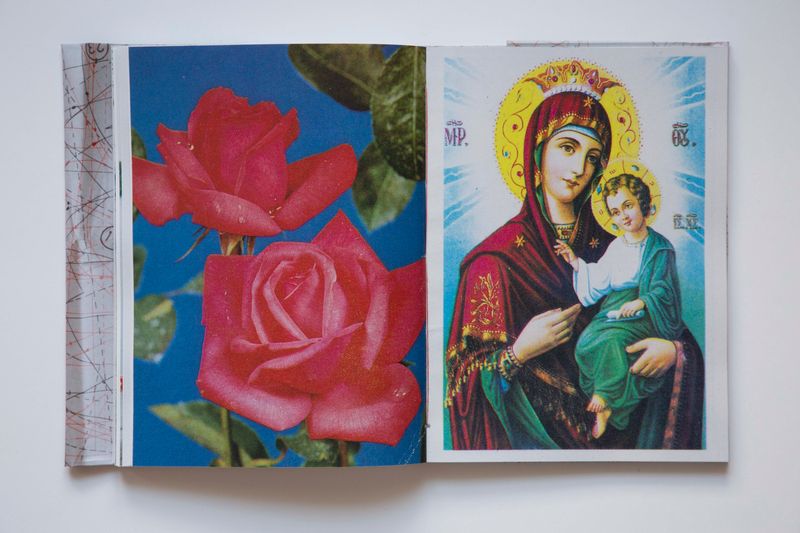

My grandparents lived for many years under the illusion of returning home. Their long-delayed return had become impossible. When the war began in 1991, my grandfather started to scratch out any link he found, leaving scars in books and magazines. As a 9 year-old, I couldn’t understand these issues. Today, I see his anger stemming from being a powerless witness of the violent disintegration of his country which, at the same time, restricted the mobility of an entire population whose lives had oscillated between France and Yugoslavia. For my grandparents, who remained apart from French society, their flat was like their own little country.

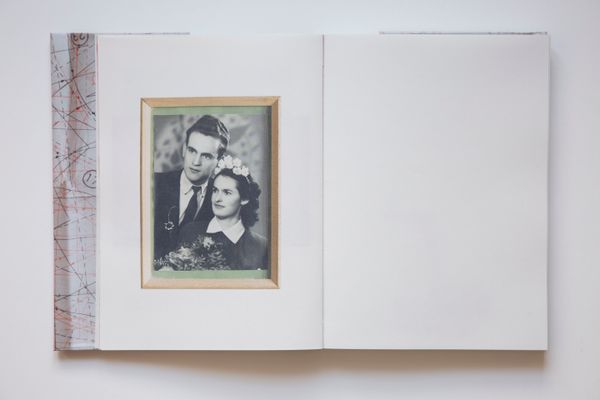

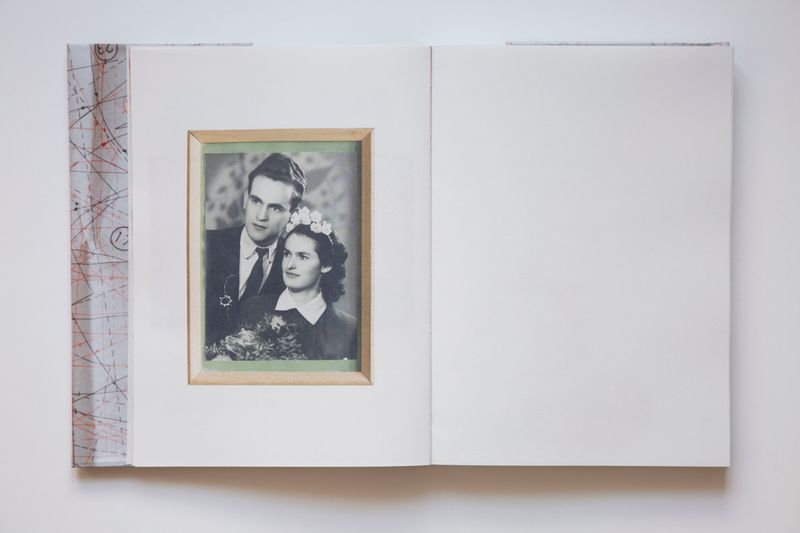

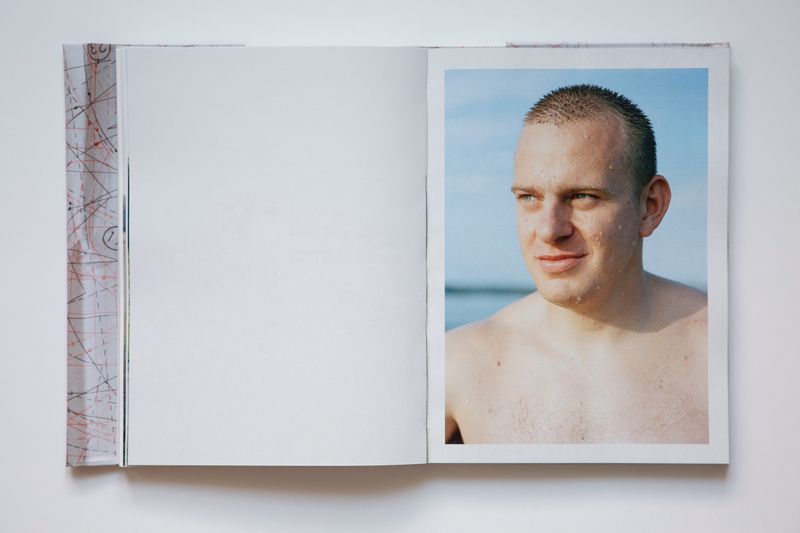

After their death, the flat on Rue Désiré Chevalier was left frozen in time. Before they passed, the language barrier between us made communication very fragmentary, so it is through family albums, archival documents and my own pictures that I’ve been able to reconnect to them, and understand my own connection to a country that no longer exists. From their apartment, behind closed doors, I reinterpreted their memories and archives. Exploring their photo albums, spanning a period of fifty years, I discovered how they would photograph each other, always one after the other, from the same point of view.

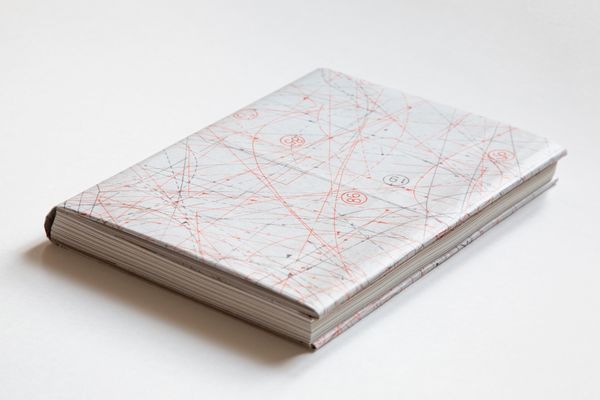

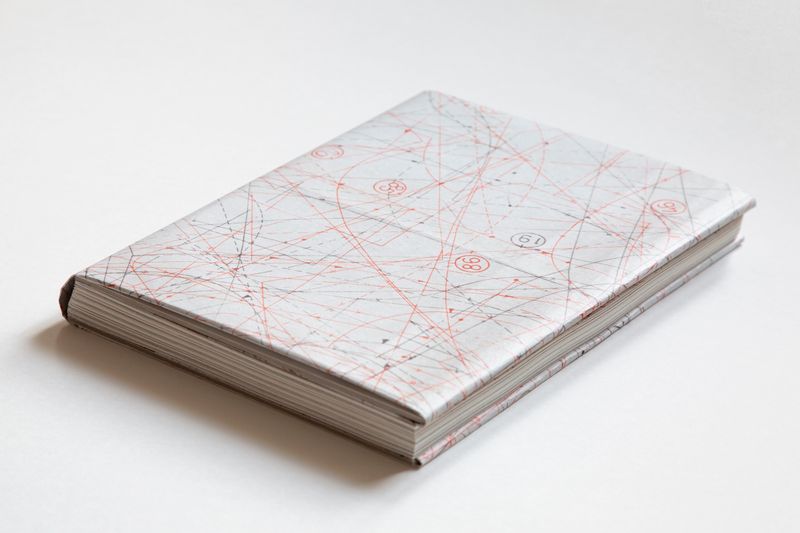

This is a story in which past and present, native home and adoptive home, France and former Yugoslavia, are closely interwoven. Memories are weaved together like the embroidery my grandmother used to sew, a metaphor between the memory of home country, where the heart remains, and the life one builds in a new country, leading to an unachieved emotional landscape drawn from both lack and fulfillment, absence and presence.