If you can read the ocean you will never be lost

-

Dates2013 - Ongoing

-

Author

-

Recognition

"If you can read the ocean you will never be lost" documents the final residents of the last U.S. leprosy settlement, Kalaupapa. This project is a historical reckoning of Native Hawaiian resilience, colonial history, and the contested future of the land.

If you can read the ocean you will never be lost, 2013–ongoing

This expanded documentary project, spanning over a decade, chronicles the final years and enduring legacy of the last registered residents at Kalaupapa. As the sole remaining U.S. leprosy settlement for individuals with Hansen’s disease (known in Hawaiian as Mai Ho'oka'awale, 'the separating sickness'), this work acts as a historical reckoning. It examines disability and environmental activism, documents Native Hawaiian resilience against a colonial past, and investigates the profound question of the land’s contested future. Gaining access to this peninsula requires a difficult, multi-leg passage, underscoring the necessity of external sponsorship to continue this essential documentation.

The geographically unique Kalaupapa Peninsula is a landscape of profound contradiction. From 1866 until isolation laws were lifted in 1969, it functioned as a site of forced exile yet remained a home and a living testament to resilience. Challenging colonial narratives, my project contributes to a reconstructed Kalaupapa history, restoring the narrative of ʻohana (family) and compassion practiced by the original inhabitants who took in the first exiles as kin, a cultural act of care that the Saint Damien narrative obscured.

The peninsula's defining feature is the towering Pali (sea cliffs), which are the world's tallest, plunging nearly 4,000 feet into the Pacific. This dramatic geography was strategically exploited by the Republic of Hawaiʻi, the government established after the 1893 overthrow aided by U.S. forces, that solidified Kalaupapa as a century-long prison and hospital. This regime completed the forcible removal of all original inhabitants (kamaʻāina, 'child of the land') in 1894–95 to protect the economic interests of American-owned plantations. Yet, the Pali and the surrounding sea offered familiar passage, not separation, to Native Hawaiians who lived there for centuries. This history is underscored by over 8,000 graves, a mix of residents and ancient Hawaiian burials, revealing a permanent homeland.

My practice combines photography, moving images, sound, and archival voices, and is organized around three critical integrated thematic areas that capture the past present and contested future.

The first chapter uses the landscape to articulate how the geographical barrier of the Pali (sea cliffs) which enforced the quarantine has ironically resulted in one of Hawaiʻi's most undeveloped and pristine environments. My imagery documents the monumental geography from the aerial "Pali (Sea Cliffs)" and punishing "Winter Surf" to the strenuous "Trail to Kalaupapa." This is juxtaposed with infrastructure like the "Broken Stairs" and the "Former Tour Bus" being reclaimed by vegetation, starkly illustrating the conflict between preservation mandates and the natural forces of abandonment. The visual argument emphasizes that the historical isolation, while tragic, physically froze the peninsula in time, creating a pristine landscape where history is visibly preserved and written into the earth itself.

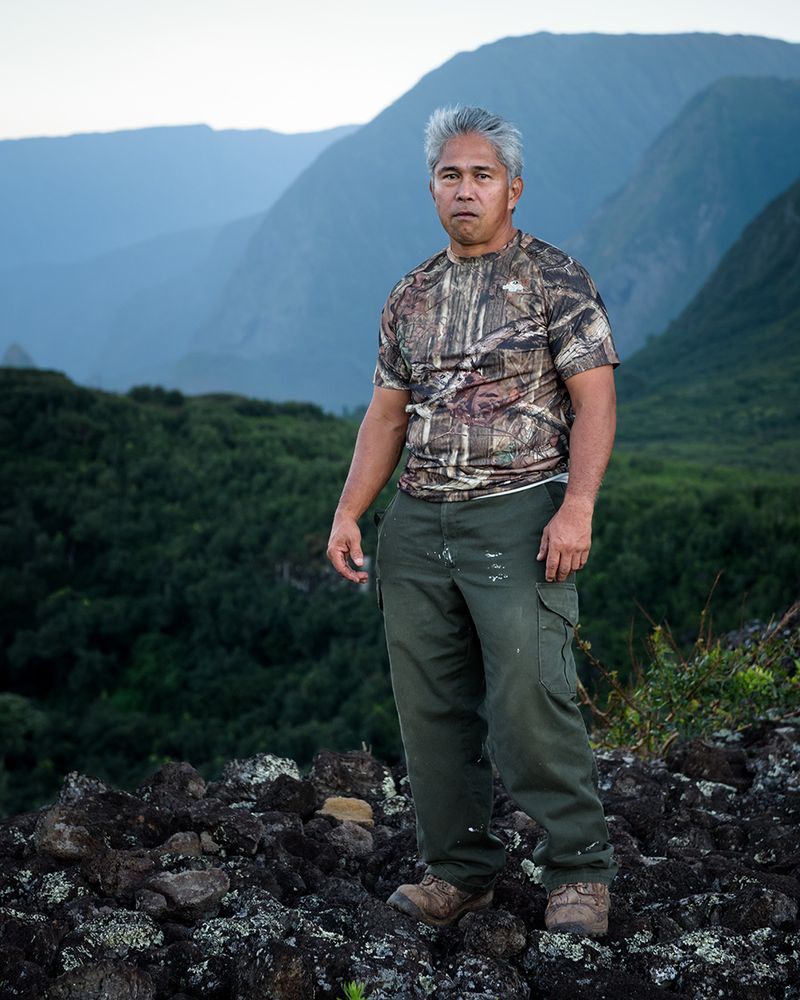

The second chapter centers on the people who give Kalaupapa its meaning, directly challenging colonial narratives by focusing on resilience and agency. The work documents the last generation of residents through sensitive portraits of former residents, including "Uncle Eddie" and "Uncle Boogie" who has since passed, recording the community during this critical period. This human narrative is grounded in place through vital environmental portraits of Native Hawaiian National Park Service staff, such as "Lansen" and "Kirk," highlighting the necessary inclusion of local voices and heritage in the land's management and its future. Images like "Paʻakai (Sea Salt)" and "Fisherman's House" further affirm Native Hawaiian self-reliance and enduring connection to the land and sea.

The final phase of this project focuses on two urgent, time-critical tasks that require immediate funding. The first is documenting the remaining last generation of residents through intimate portraiture, a task that must be completed now due to the advanced age of the surviving population. The second is finalizing the museum and archival materials. This requires returning to the Kalaupapa Museum to complete the archival phase, extensively photographing historical materials like the "Ancient Hawaiian Poi Pounders," the "Former Patients' Foot Molds No. 1–3," and original translated documents to finalize the project’s reconstructed history.

This work entered hiatus when the COVID-19 pandemic enforced an isolation not seen since before the laws were repealed in 1969. Now that the settlement has reopened, funding is urgently required to facilitate my immediate return to complete the final two chapters. With only three patients remaining at the settlement, the project must be completed now to ensure this sensitive history and the portraits of the last generation are fully realized.

The final body of work investigates the peninsula's transition from an indigenous homeland to a prison, a hospital, and now a National Historic Park. The conflict over the land’s future is clearly defined as the National Park Service (NPS) seeks to establish a permanent park while local residents and descendants advocate for a return to homestead land. The final body of work will be presented in a solo exhibition at the Molokaʻi Public Library (Topside) and the Kalaupapa National Historical Park & Museum (Backside), featuring panel talks with local residents. The Women Photograph Grant is vital for funding my immediate return to Kalaupapa, ensuring this critical inquiry is fully realized and allowing me to share this reconstructed history globally with the dignity the last remaining residents deserve.