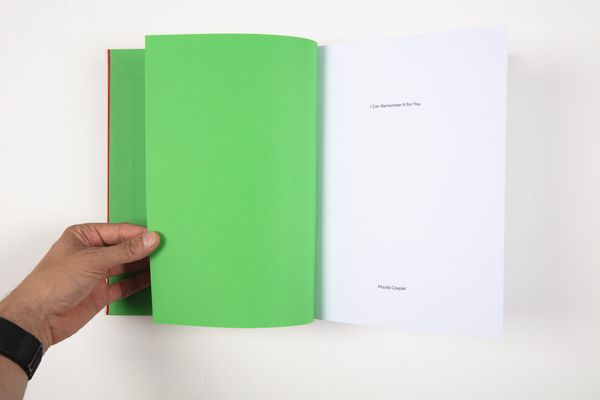

I Can Remember It For You

-

Dates2025 - 2025

-

Author

- Location Switzerland, Switzerland

-

Recognition

A correspondence of letters between my former and present self, which enables a reflection on my family albums in a contexte of migration trying to understand how memory constructs our stories through family pictures that captured a tragic moment in time.

As a child, growing up in Germany, Canada, and then Switzerland, I would spend countless hours looking at the family photo albums my parents had created since I was born in Krakow, Poland. I would imagine my life’s history flipping the plastic sheets full of pictures. My parents and relatives would contribute to building this history in my brain, by telling me a few stories here and there.

When we arrived in Canada, my name was unofficially switched from Maciek to Mathieu, so the Québécois people wouldn’t have too much trouble with the pronunciation of this Polish name. Yes, it was to simplify this aspect of my everyday life, so I wouldn’t have to explain where I was from or how to say my name correctly, but it was probably also not to attract any attention to who we really were: refugees from an Eastern European country. I guess my parents learned to keep a low profile because they grew up in

a country with communist political leaders. You had to be careful whom you told the truth to, even your neighbor could rat you out. In fact, this is exactly what happened to my grandpa. His neighbor, a man he said hello to every single day, ratted him out. After this, both my grandparents ended up in jail for several months.

When I was born, my parents decided to flee the country, which was around 1988. We were lucky to have an aunt in Germany who could « invite us » to spend the holidays at her place. That was the only way we could leave without being harassed by the government. So we packed our bags and left everything behind.

We ended up in refugee camps in Germany. We spent about two and a half years there, sometimes in foster families that would at times treat us

like lesser people: not feeding us properly or enough, turning off the heating system, and cashing in the state-sponsored money for themselves instead. But my parents and other families got tired of this and told the police, so we got moved into double-family apartments.

There we could take part in the lottery, but not the regular lottery where you could win a fortune, no, not that one. I mean we won a fortune, so to say. We won the right to move to Canada because of French lessons my dad took twenty years earlier in high school. Among God knows how many families that applied for this, we were the ones allowed to leave those horrible camps.

The only story my mom told me about these camps growing up was that « the Germans would bring us crates and crates of apples full of pesticides », and that she would get sick eating them.

Canada was a great time for me, it’s only later in life that my parents told me that it wasn’t so fun for them. I was a kid, so I was thinking of kid stuff back then, everything was fine for me. My parents had to figure out a new life for themselves, and it wasn’t easy. My dad studied nursing in Canada, but his Polish high school diploma was not recognized by the state. We had some sort of luck again, and my dad found work in Switzerland. So after a few years in Canada, we moved back to Europe.

I remember it being strange because I was losing all of my friends, things were changing in my mind, I was old enough to understand what was happening to me. We arrived in Switzerland, from a one and a half million-people city to a four-hundred-person hole in the middle of nowhere. I saw cows for the first time in my life.

I spoke French, but it was a French other kids couldn’t understand: Québécois. I could understand them just fine, but I could feel a gap between them and me.

In Switzerland, I started playing around with photography. I would take the family camera and explore this intricate machine.

In my early 20s, my parents casually told me some stories about the reasons why we left my birth country, Poland. This is when I learned all those stories, right around the age of

23. Since then, I’ve been asking them more and more details about some of those stories, which sparked the appearance of new anecdotes about those years and their own past, my grandparents’ and great-grandparents’ past... I started learning a whole lot about my own life’s story. I’ve always known my history, but it was incomplete. It wasn’t false, I wasn’t lied to, but some details of my past had been put aside. And when I discovered them, it felt like I had my « real history » in my hands, so I started to ask people to call me by my real name from there on: Maciek. I remember feeling a little ashamed of telling people my real name up until that point. Fearing they would see me differently, but now I know where this fear comes from. My parents, grandparents, and great-grandparents were constantly afraid of the people leading their cou try, and this stuck.

At that point, I had already investigated one of my memories in a photo- graphic work titled “If I Could Only Remember”, back in 2017, during my photography studies. In it, I questioned the reality of what I consider to be my first memory, which coincided with us leaving the refugee camps in Germany to go to Canada.

Now I’m trying to ask my parents everything I can about the past. But first, I have to understand myself, understand how I saw things back then, back in Germany, Canada, and Switzerland.

In an exchange of letters and postcards, I ask Maciek about my past, and he asks about his future. I remember my past, and the past version of myself remembers his past with a clearer image. I forgot some details of his past but have knowledge of my present. I now need to put the fragments together to have the whole picture in front of me, so both (hi)stories build one and create this space of understanding for each other. In this correspondence of letters between the two fragments of myself: my former self and me as my present self, I reflect on the pictures in my family albums, the stories that were told to me when I

was a child and later on in life. But I also enable a reflection on this part of history, and try to understand how my memory constructs our individual and collective stories through family pictures that captured a somehow tragic moment in time. One of those pictures is a photograph of my mother and me in what, as a child, I didn’t know were refugee camps in Germany. In this picture, I recognize my mother, but some- thing is off. She looks sick. And one thing that’s always been engraved in my mind is that in this picture, I’m holding an apple, or what I’ve always thought to be an apple. All of these family pictures have allowed me to have a different reading of images according to what I know about them.

I don’t want to figure out the truth, that’s not the point of this. I just need to understand that I wasn’t alone in this whole story. History is something shared by everybody, and I think that before I was told my life’s history in my twenties, I thought that I was building my world alone, on my own. But that’s not how it works. This apple I thought I was holding in this picture of my mom and me was just the reflection of my past. Yes, it was something else I was holding in reality, but I thought I was holding the apple, that apple my parents had told me about all of those years since I was a kid.

I grew up with a glimpse of my history, and that’s enough. Today, I can get deeper into what made my past, the past of my family, and the past of my birth country.

This family story comes from suppression, the letter form allows me to have a form to tell history in a different way, based on experiences, contradictions. It allows me to question all of this and create a voice that can speak these stories from different approches. It allows me to question my fragments of memories and find a voice for these fragments to grow.