Down by the Hudson

-

Dates2013 - Ongoing

-

Author

- Location Poughkeepsie, United States

-

Recognition

-

Recognition

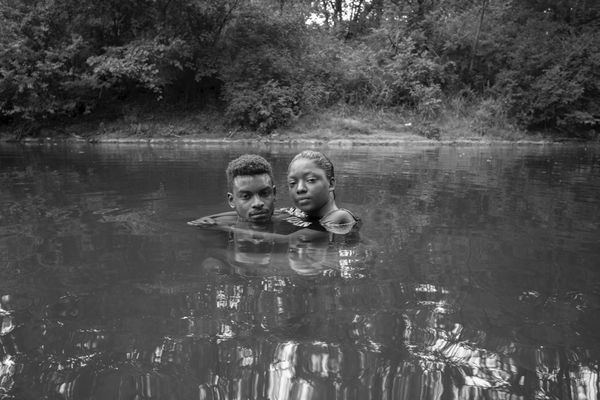

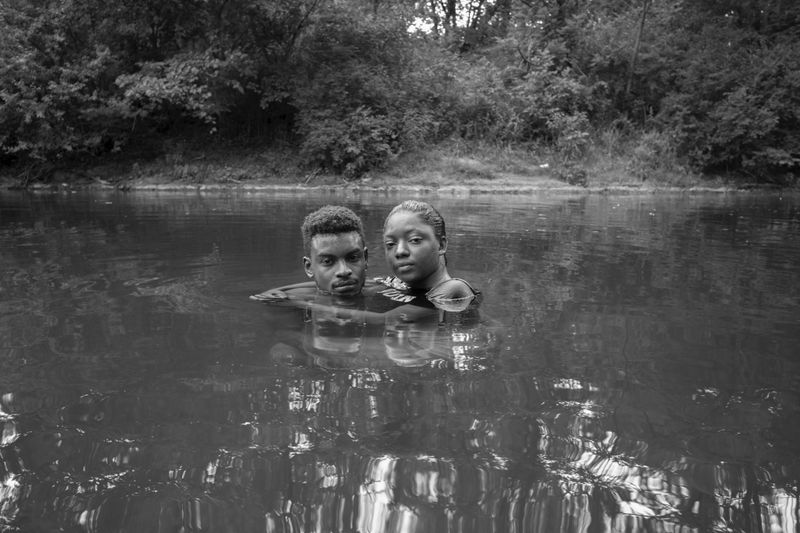

‘Down by the Hudson’ is my personal ode to an Edenic creek in Poughkeepsie, NY, a small town in New York State where I lived, on and off, between 2013 - 2024 and where I continue to make work.

‘Down by the Hudson’ is my personal ode to a creek in Poughkeepsie, NY, a small town in New York State where I lived, on and off, between 2013 - 2024 and where I continue to make work. 'Down by the Hudson' is the product of collaborative relationships with the people I photograph. With each of the photographs I want to convey a lyrical, loving expression of the playful exchanges between me, the photographer, and the people I’m photographing. These photographic exchanges can lead to something that feels like a transcendental clarity, vulnerability, and tenderness.

This work cannot exist apart from its political context. In 2016, the presidential and local elections were almost neck-and-neck between political parties in Poughkeepsie, to the point where you could have fit the difference into a bar on a Saturday night. The day after the election, the sense of tension and conflict became palpable as I walked down Poughkeepsie's Main Street. I learned that in the 1990s, IBM's local headquarters downsized and left thousands unemployed. In many ways, Poughkeepsie is like countless other small American towns grappling with the effects of post-industrialization. This heated political moment marked a turning point for this project. It wasn’t only about understanding this mythologized conception of America, but it was also about grappling with this conflict through photography and its extraordinary capacity to bridge specific moments and details with broader notions of the universal and the collective.

It was during this time that I started going to a local watering hole, a modern-day Eden tucked away behind a drive-in movie theater on the outskirts of town. The watering hole became a central component of my work because it represented an idyllic space where people from all walks of life came together and let their guard down. The more time I spent at the watering hole, the more I wanted to convey the struggles and beauties of this town with care. For several years I have photographed at this watering hole, developing close relationships with many of the people I collaborate with and sharing the work with them as it develops. I am fascinated by the ways in which people carry themselves in this space, how the natural environment brings people together; in fact, county regulations forbid people from gathering in this space, and so the whole experience of simply being at this watering hole is informed by this sense of joyfully illicit activity. Increasingly, I'm interested in the idea of the creek as the protagonist. We are just passing it through it, but what has this space stood witness to? How many people have fallen in love at this creek over the millenia?

For additional reference, please see the below texts by various writers on 'Down by the Hudson', below:

1. Text by Legacy Russell, Director, The Kitchen, New York

I so appreciate the dream-state presented in ‘Down by the Hudson’, and the complex negotiation of boyhood, as it stands in the tension of a gendered binary. The surreality found in mirroring. What water does, and how our bodies can becarried by water as a site of play, pleasure, joy, healing.

2. Text by Matt Carey-Williams. Former Director of Victoria Miro Gallery. Currently running an eponymous gallery based in London.

Caleb Stein’s Watering Hole:

The Baptism of Identity in the Pool of Perpetuity

Tucked away in the Hudson River Valley is the small town of Poughkeepsie. It is located in a landscape so stunning that it inspired an entire school of American painters. Artists such as Thomas Cole or Albert Bierstadt were all eager to evince some of the romance and rebus of the American experience; celebrating those modern dynamics of discovery and establishment through an articulation of the timeless grandeur of geography. For the Hudson River School artists, the architecture of contemporary America – its pillars of belief; its structures of meaning - was, ironically, to be found in the ancient valley’s rolling hills, winding river and lush woodlands. It was there one could truly understand what it meant to be American. What it meant just to be.

Space or, more particularly, place has always been employed by those artists seeking to unravel the intricacies and delicacies of identity. Cole and Bierstadt both used the generic vocabulary of the Pastoral – land, water, sky, setting and rising suns and their majesty of light - to enunciate a quite specific vernacular of Americana. 170 years later, the British artist, Caleb Stein, is writing similar love letters to this region and, specifically, the town of Poughkeepsie to understand the mythos, pathos and bathos of America and Americanness. It is a subject he has explored since 2013, having lived in Poughkeepsie for over several years, and it remains his overarching quest, informing this new body of his work, Down by the Hudson.Poughkeepsie gets its rather unusual name from the Eastern Algonquian-speaking tribe from New York and Connecticut called the Wappinger. It means “the reed- covered lodge by the little-water place” and refers to a stream or spring that feeds into the Hudson River.

Water has fascinated Stein since he was a young boy. He is drawn to its healing properties. It is an ‘environment’ in which humans function differently. Quite literally, we feel less pressure when we’re in water. Less gravity. Less stress. So it is that most of the images from this body of work are taken at a place called The Watering Hole. A little oasis on the outskirts of Poughkeepsie with cool, soothing waters that lead down to the Hudson and which have provided sanctuary for numerous Poughkeepsians from hot summers, stressful elections and pandemics. It’s time for us to take a dip.

Stein’s attraction to water, and his desire to capture others’ delight in and for it, is not new. Any number of comparisons can be made, but one would struggle to find a better one than Thomas Eakins’ The Swimming Hole (1884-85, Fort Worth, Amon Carter Museum). Both artists present their respective natural pools as places of escape or refuge. Eakins amplifies and classicizes that perspective by depicting his protagonists naked. Whilst Stein does not capture any skinny dippers, he, like Eakins, does secure a sense that the pool is a somehow sacred space; one that invites togetherness yet allows for otherness. A communal space where everyone is the same yet allowed to be different. An oasis that is gloriously ordinary, offering safe haven from this most extraordinary world of ours, right now. Stein’s photographs serve to gently push our heads under the water of The Watering Hole, momentarily pausing the endless vicissitudes of life caused by this virus, sharing the calm and quiescence that is etched over the faces of many of The Watering Hole’s visitors.

There is another reason to employ such a juxtaposition and that is both Stein and Eakins’ focus on masculinity. Unlike Eakins, Stein’s contemplation of masculinity is not libidinally or erotically charged. He is interested in capturing moments that problematize the language or codes of masculinity (and, by extension, heterosexuality) and illuminate the innate vulnerability that all men experience. We see it in casual embraces; long gazes into the distance; the baptismal propensities of the water covering these bodies. That examination of masculinity is seen in the journey from adolescence to adulthood; it plays out in various watery vignettes here in The Watering Hole. Solitary figures such as Braily and TaeShawn present one kind of visual trope of masculinity: a certain confidence or truculence that cannot help but elicit the tremulous vulnerability of these young men. That perfume of flux contrasts with Skyler & Malikai or Fred & His Twin; one confrontational, the other cooperative; one youthful, the other experienced. Boys buck like deer as two muscular brothers help one another look for something lost. In turn, these photographs differ fromStein’s depictions of groups of boys or men. Masculinity here feels charged, animated; sometimes frivolous, other times adversarial. Even though they’re just teenagers, Erin & His Friends do not look like people you would mess with. They try hard to look like people you wouldn’t want to mess with. Identity is but a triangulation of inflection, introspection and projection, after all. In a sense, Stein unpicks at the various coats of masculinity worn by his protagonists, observing the difference between a winsome, unburdened Michael, owning his pictorial space, and the two Trump supporters, Brendan & Sean, more guarded and distant, overwhelmed by their environment. The most important point is that, here in The Watering Hole, such differences are openly expressed and embraced; masculinity now as fluid as the waters in which these men and women bathe.

Most people in this little oasis live in Poughkeepsie, but they can be found across the annals of myth and time. They are men and women whose stories – Classical and Biblical - are inextricably tied to the jeopardy and justice water provides, colouring several tropes of identity as a result. So it is that Sanjay is Narcissus. Tales of yore provide parables for us all today. Fables of right over wrong; good over bad; life fending off the jaws of death. I can’t help but spy the restoration of Susannah’s virtue in Summer; see the attack on Actaeon by Diana in those young men with their angry huskie. In all these moments Stein keeps his focus very much on the figure in landscape yet - wittingly or unwittingly - that landscape shifts from geology to politics; from geography to identity. From moment to myth to memory. One cannot help but see Stein’s figures through this kaleidoscopic lens of his. One that deliberately fuses paragons of the past with paradigms of the present. Therein lies the timeless beauty; the delectable déjà vu of these images and Stein’s process.

We have all visited The Watering Hole in Poughkeepsie before. Many times, over many visits, crossing many millennia. It’s down by the Hudson, by the Styx, by the Jordan and the Euphrates. Whilst Stein’s images are contemporary portraits of a time, place and people, they are also those little snippets excavated from the ether of time, sharing and communicating the fears and hopes; loves, lives and dreams of time immemorial. Stein takes us down by the Hudson, at a time when life is full of irresolution. There we seek absolution in solution; hope in history; peace and harmony that only The Watering Hole can provide. Stein’s powerful, achingly beautiful Down by the Hudson is a dip in the waters of serenity, community and solidarity. A dip we all so desperately need today.

3. Text by writer Amitava Kumar, Guggenheim Fellow and Chair of the English

Department at Vassar College.

We are water.

Most of the human body is water. How much of the world is water? Here, from that ocean of common knowledge called Wikipedia, is the response to that question: 71 percent. ‘About 71 percent of the earth’s surface is covered by water, and the oceans hold about 96.5 percent of all the earth’s water. Water also exists in the air as water vapor, in rivers and lakes, in icecaps and glaciers, in the ground as solid moisture and in aquifers, and even in you and your dog.’ (Even in you and your dog—see p. _ of Caleb Stein’s Down by the Hudson.)

And yet, and yet. The fight in the future will not be for land but for water. On some sad nights you have sat at home, sipping a drink maybe, watching a documentary from which you learn that women and children walk for hours to bring back to their shanties a pail of water. Where it is scarce, and even where it is abundant, water calls to us.

I’m talking from experience. The other evening, in a report about Delhi, I heard a man say ‘Even if you try to borrow water from someone, you won’t get it. You can borrow money, but you cannot borrow water.’ And then, on a bumper sticker on the car parked next to mine in the parking lot I saw these words:

WE BELIEVE

LOVE IS LOVE

SCIENCE IS REAL

BLACK LIVES MATTER

WATER IS LIFE

NO HUMAN BEING IS ILLEGAL

FEMINISM IS FOR EVERYONE

KINDNESS IS EVERYTHING

What is the meaning of that line in the middle? Water is life. It is the slogan of the protest at the Standing Rock Indian Reservation against threat posed by the Dakota Access Pipeline to the Missouri River. In Bolivia, in Nicaragua, in Egypt, in Tunisia, in South Africa, there have been movements of social protest against the privatization of water.

In a 2005 commencement speech delivered at Kenyon College, David Foster Wallace tells a story about two young fish coming across an older fish swimming the other way who nodded at them and said, ‘Morning, boys. How’s the water?’ The two young fish kept swimming awhile before one fish turned to the other and asked, ‘What the hell is water?’ In Foster Wallace’s speech, water is a metaphor. He is saying that ‘the most obvious, important realities are often the ones that are the hardest to see and talk about.’ Water is the tedium and frustration of daily life; water is also our default response to it, a response full of anger and impatience and judgment. Against the automatic and unconscious assumptions about our own importance, Foster Wallace wants us to show awareness and pay attention. Once we start doing this—and here I have Caleb Stein’s camera in mind—we transform ourselves and the world.

Foster Wallace says, ‘It will actually be within your power to experience a crowded, hot, slow, consumer-hell type situation as not only meaningful, but sacred, on fire with the same force that made the stars: love, fellowship, the mystical oneness of all things deep down.’ Stein has been attentive and aware and disciplined in his photographic practice, all these are the qualities that Foster Wallace recommends. With his camera in hand, Stein has chanted, ‘This is water. This is water.’

In Stein’s photographs, water flows through an eternal summer of youth. The bodies that we see in a musical dance wear a skin of water and inextinguishable light. We are in nature. We are looking at bodies at play in the public commons. Equally astonishingly, all this refulgence is far away from corporate banners and the glare of advertising. We are away from all the faded walls and broken windows that speak of urban detritus. No closed signs, no abandoned buildings, no arid talk of postindustrial decline. No pandemic, no masks. The creek is flowing but time has stopped still. There is no burden of history here. You are with your friends, afloat in the water. It is not only your body—it appears even your breath is finally weightless.