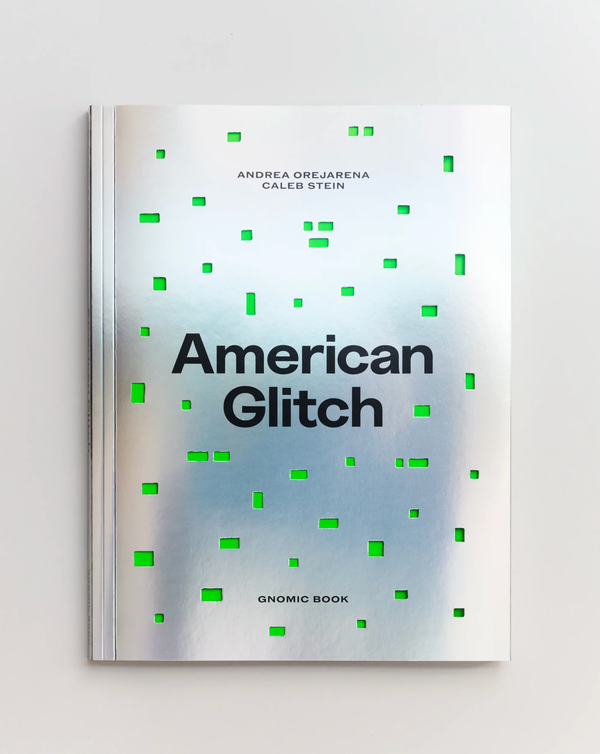

American Glitch

-

Dates2020 - Ongoing

-

Author

- Location United States, United States

-

Recognition

American Glitch (2020-2024) explores the intersection of documentary and fictional elements, examining the connection between AI, mythological narratives, disinformation tactics within the context of our networked present.

Our process was like a deep dive into a labyrinth of imaginative, poetic fragments shared by anonymous people from around the world.

– Orejarena & Stein

The following text was written by curator Nadine Isabelle Henrich for the solo museum exhibition 'Tactics & Mythologies: Viral Hallucinations' at Deichtorhallen, Hamburg:

American Glitch (2020–2024) explores the intersection of documentary and fictional elements, examining the connection between mythological narratives and disinformation tactics within the context of our networked present.

Over the course of four years, Orejarena & Stein have built an unusual archive, amassing over 2,000 photographs and AI-generated images, many of which circulate online within the context of humor as a strategy of cultural resistance, conspiracy theories and the popcultural imaginary of simulation.

This artistic archive reveals a repertoire of image types, codes, patterns, and motifs that form a dynamic typology within the ever-expanding visual world of disinformation. Orejarena & Stein have transformed this examination of images—some of which playfully question our relationship to reality—into their own photographic concept, loosely inspired by an atlas of locations that carry myths of constructions of truth and simulation across the US landscape.

By analyzing the metadata of these image files, such as locations tagged on social media and other contextual information, the artists were able to trace the origins of the archived images. This analysis resulted in the first cartography of conspiracy theory locations in the USA, which serves as the starting point for the exhibition »Tactics & Mythologies.« Following this map, the artists embarked on a journey through the US to document it as a »simulation.«

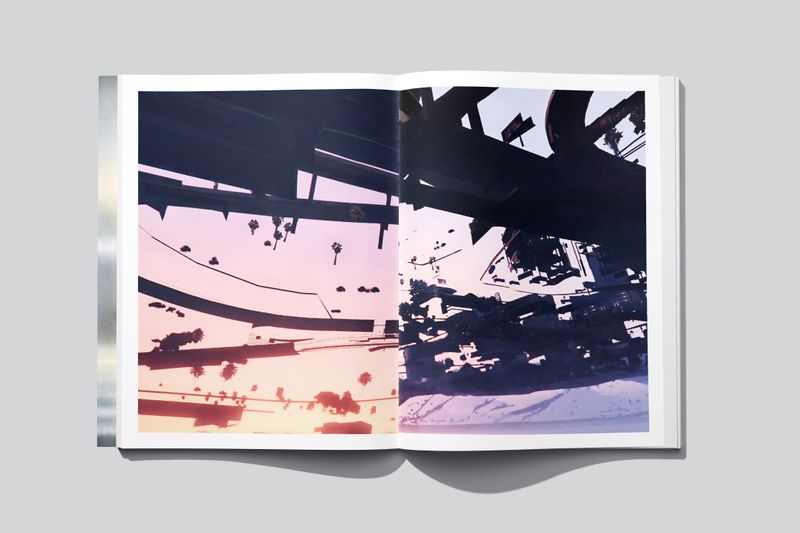

Their symmetrically composed photographs, taken frontally with a Hasselblad medium-format camera, align with the pictorial tradition of canonical conceptual photographers like Ed Ruscha, as well as documentary-driven projects that conduct a photographic topography of the US. In a social present shaped by viral fictional narratives, the project navigates the space between documentation and fiction, physical and virtual realms, and particularly their hybrid intersections that characterize the American landscape—where simulated environments and manifest fictions converge.

The large-format color photographs are presented for the first time in spatial dialogue with an image archive sculpture specifically developed for the exhibition.

The collected images are projected as temporary, choreographed and layered constellations onto transparent cubes, flowing past the expansive landscapes and staged architectures in Orejarena & Stein‘s photographs like swarms of viral hallucinations. The archive sculpture reflects Orejarena & Stein‘s ongoing exploration of visual practices online and their dynamic archives as a collective subconscious.

The following text was written by David Campany to introduce the artist book, American Glitch. Gnomic Book. 2023.

The Glitch is in Us

Andrea Orejarena & Caleb Stein’s American Glitch so brims with its own inventive play and suggestive commentary on its motifs and methods, that it is probably best not to write about it directly. They have made a kind of essay in visual form, and I am thinking of the root of the word ‘essay’ in the French ‘essayer’: to test, to try out. Theirs is an act of creative and intellectual speculation, and as such it invites something similar from us. So instead of any direct writing, it is the root of another word I would like to reflect upon here: glitch.

But first, a story. I was six years-old when, one summer Sunday morning, I awoke and opened my eyes wide. For a disarming second or two, it seemed everything remained completely dark. The sun then rushed to my retinas and I saw my room, bright and clear. With the kind of solipsism that is excusable in a little kid, combined with some mixed-up ideas about God and me, I naturally assumed He had forgotten to send the light my way and it had arrived fractionally late. I was sure God had given himself away with a revealing error, of the kind we might now call a ‘glitch’. I didn’t tell anyone; it was our little secret. Then I grew up. I have no idea what actually happened that morning, but I am pretty sure it had nothing to do with an accident-prone celestial overseer. Perhaps I needed proof and imagined the whole thing. This is not uncommon in children. Or adults, for that matter.

Although the origins of the word ‘glitch’ are somewhat obscure - deep in German and Yiddish - there is plenty of evidence that it was common parlance in North American radio and then TV studios in the 1940s and 50s. Back then, the meaning was quite straightforward. It was used to describe small technical errors. From time to time, on-air announcers would use the word when apologizing to their audiences for such mistakes. But over the last thirty years or so, ‘glitch’ has become part of everyday language, used at first to describe the minor failures of the new digital technologies that were becoming familiar household items in the 1980s and 90s. The way a scratched CD skipped was very different from the way the needle on a scratched vinyl record skipped. Digital camera pixels were different from film grain. The corruption of a floppy disk or hard drive produced kinds of information dropout and distortion that were unlike their analogue predecessors. Digital faults are different because they are outward signs of electronic processes that are essentially invisible and inaudible, locked away in computer chips and circuitry that, even if you opened them up, could reveal nothing to the eye. Slowly, ‘glitch’ came to refer to digital error specifically. Glitch techno music was my favourite creative adoption of digital error. Within two years it went from the underground club scene to a Madonna album. Last year, as if to confirm the populism of the word, it became the title of a Taylor Swift song.

Meanwhile, something darker has happened. ‘Glitch’ has also come to mean not just error, but significant error. A disturbing sign indicating a deception. Nevertheless, this meaning has been there for a while. Back in the late 1990s, the movie The Matrix had used technological glitches in this way, as plot devices. Slippages in everyday perception are taken by the protagonist, played by Keanu Reeves, as signs that his reality is a grand illusion that he must confront. It took a while for the notion of the ‘glitch in the matrix’ to become a kind of conversational shorthand, used ironically by some and seriously by others to indicate the presence of sinister forces that wish to remain hidden but give themselves away haphazardly now and again. But we humans are by nature deceptive, with ourselves and with each other, so the whole idea of the revealing error is really as old as us.

There is a scene in Alfred Hitchcock’s 1940 wartime film Foreign Correspondent in which the hero, played by Joel McCrea, is chasing an assassin. In a remote, flat Dutch landscape dotted with windmills the assassin seems to vanish into thin air. McCrea looks around in panic. He rests up, exhausted and at a loss. Then, he notices the rotating sails of one of the windmills suddenly stop… and begin to rotate the other way. It is an uncanny and disturbing sight. Things are not what they seem. McCrea rushes towards it, unnerved but determined. Inside, he uncovers the truth: the windmill is being used to signal to enemy aircraft in the area. That was over eighty years ago. Today we might describe the nefarious windmill as a kind of glitch. A strange anomaly that marks a tear in the veil of appearance disclosing something menacing. Think of it as a kind of visual equivalent to the Freudian slip – the misspoken word or phrase that lays bare what is really on the speaker’s mind. I will come back to this.

Hitchcock was brilliant with this kind of device, and we find it in many of his movies. It may come as no surprise that he often came up with such scenes first, and would have to structure his films in ways that gave them dramatic meaning. He didn’t always find a way. In his famous book-length interview with Francois Truffaut, Hitchcock tells of a scene in which we follow, in an unbroken tracking shot, a car being put together on an assembly line. First, the wheels are set down, then the chassis, engine, seats, steering wheel and the outer shell. As the car reaches completion, a mechanic opens one of the doors and out tumbles a dead man. “Where has the body come from? The corpse falls out of nowhere, you see!” Hitchcock exclaims to Truffaut. “The real problem was that we couldn't integrate the idea into the story. Even a gratuitous scene must have some justification for being there, you know.” In a way, the revelation that the situation comes first, that it is meaningless until it is given context and significance, is itself a kind of reality reversal. A movie’s pivotal moment, the one upon which the whole narrative will turn, may not be part of a narrative at all, until one is created to justify it. Jokes are often written like this. The punchline comes first.

The revealing glitch was taken up by many more filmmakers, particularly in the genre that came to be called the paranoia thriller. The hero - or anti-hero, usually either a naïve or disillusioned outsider - stumbles across something that seems innocently banal but which, upon closer inspection, becomes a key to unlock a covert plot or evil organisation. The hero is at first confused, has doubts about their ability to figure it out, and even doubts even about their own sanity, but their hunch is eventually proved correct. (As the strapline of the 1998 movie Enemy of the State put it, “It’s not paranoia if they’re really after you!”). The genre intensified in 1960s and 70s, coming to a head with Alan J. Pakula’s era-defining ‘paranoia trilogy’, Klute, The Parallax View and All the President’s Men. The first two were fiction but the third was based on the realities of President Richard Nixon’s devious Watergate conspiracy, the discovery of which was pure Hitchcock. Frank Wills was a security guard at the Watergate complex in Washington DC, patrolling the offices of the Democratic National Committee. One night, Wills noticed duct tape on one of the door locks. It was covering a latch bolt to prevent the door from latching shut. Wills took off the tape, and continued on his round. But later that same evening he saw the tape had been replaced. Immediately he reported it. The police arrived and searched the building with Willis. Five men were discovered, plotting to bug the place.

An innocent piece of duct tape unlocks not just a door, but a massive plot. Whatever trust there had been in government was, if not lost, then at least compromised, and perhaps for good. Up to that point nearly all paranoia thrillers had contained one such moment, in which the mask of appearance slips and the unpleasant reality is glimpsed. Looking back, it is pretty clear these films were a symptom of a dying optimism for an American democracy where politicians are presumed to represent the interests of the constituents who elect them. But once the public learns to expect the worst of government, rather than the best, the need for covert conspiracy recedes. Since the Nixon era, paranoia thrillers have continued to be made but it is striking that they are either formulaic updates, knowingly retro movies, or even comedies. Peter Weir’s The Truman Show 1998, like The Matrix the following year, was made right on the cusp of the mass take-up of the information sprawl that is the Internet. The Matrix attempted not to be futuristic per se, but to evoke cinema’s past attempts at being futuristic. By contrast, the setting of The Truman Show is a pastiche of a post-Second World War small town. Truman (Jim Carrey) is born and raised unknowingly in a giant TV studio the size of a large county, and is filmed by hidden cameras his entire life, for a worldwide audience. His world has been a 1950s-inspired picket fenced suburbia (the reference point being McCarthyist paranoia). When a huge electrical lamp fitting drops right out of the sky, Truman begins to sense all is not what it seems. Eventually he sets sail in a bid to escape, until his little boat bumps into a painted sky backdrop. It is literally the edge of his world. Nothing has been authentic, apart from Truman himself. He climbs a staircase to exit the set, and enter a reality for which he is utterly unprepared. For viewers, the film is a gloriously narcissistic fantasy in which we are permitted to identify with Truman and imagine a world in which everything evolves around just us (a little like six-year-old me imagining God had forgotten to send the light my way). The Truman Show and The Matrix, like all movies structured around paranoia or conspiracy, makes us feel both important and duped; and important because we are duped. We are the reason for the vast conspiracy. The world appears to revolve around us, and it is from us that the dark forces must withhold their truth.

Last night I watched the comedian Dave Chappelle host Saturday Night Live. At one point, he made a suggestive account of Donald Trump’s appeal to American voters:

“He's what I call an honest liar. And I'm not joking right now, he's an honest liar. That first debate, I'd never seen anything like it. I'd never seen a white male billionaire screaming at the top of his lungs. 'This whole system is rigged!' he said. And across the stage was a white woman, Hillary Clinton and Barack Obama sitting there looking at him like, 'No it's not.' […] And the moderator said, 'Well Mr. Trump if, in fact, the system is rigged as you suggest, what would be your evidence?' Remember what he said, bro? He said, 'I know the system is rigged because I use it.' […] No-one ever heard someone say something so true and then Hillary Clinton tried to punch him in the taxes. She said, 'This man doesn't pay his taxes!’. He said, 'That makes me smart!' And then he said, 'If you want me to pay my taxes, then change the tax code. But I know you won't because your friends and your donors enjoy the same tax breaks that I do.' And with that, my friends, a star was born. No one had ever seen anything like that. No one had ever seen somebody come from inside of that house outside and tell all the commoners ‘We are doing everything that you think we are doing inside of that house’. And he just went right back in the house and started playing the game again.”

In other words, while there may be petty deceptions, there is no grand cover-up. Trump’s gambit has been to hide in plain sight, to play into popular cynicism, and simply say it is not he who is crooked so much as the system that benefits all who have power and money. (Hiding in plain sight was also another classic Hitchcockian device). In a way, Chappelle’s take, told with dark humour and schadenfreude, echoes another comedian, the late George Carlin: “They’re out in the open now. They are not even trying to conceal it anymore […] You don’t need a formal conspiracy when interests converge. These people went to the same universities, the same country clubs, they have like interests and they know what is good for them.”

The real conspiracy, so Chappelle, Carlin, and Trump all suggest, is that essentially there isn’t one. The world is run not by conspirators, but by ‘honest liars’, which is to say by selfish cynicism that leads to exhausted acceptance. No surprise there. They are doing everything that you think they are doing inside of that house. The real trick is not anything that is hidden so much as how this open situation, abetted by a culture of distraction and ever-shorter news cycles, dissipates outrage and encourages complicity. “The rigged system is the only game in town, so play it best you can,” it seems to say. It is what the British writer Mark Fisher called Capitalist Realism. The constructed belief that there is no alternative.

The appeal of conspiracy then, and the appeal of its revealing glitch, is that it centres us, in our exclusion and in our moment of special discovery. We feel valued and find value in the same way the paranoia thriller allows us to identify with the underdog who stumbles upon the secret. But the true horror of the cynical world is that all it wants is to recruit us into its unimaginative way, without conspiracy. Conspiracy flatters us with presumed attention, when the reality is that the prevailing order does not flatter us, nor centre us, nor even care to deceive us. In the face of indifference, the desire for conspiracy is a desire to feel one matters, that one is worth deceiving. To hold on to any ‘glitch’ in the hope that it is the key to a hidden order is to miss the point.

I am reminded of the notorious, self-deluding statement made in 2002 by Donald Rumsfeld, President George W. Bush’s secretary of defense at the time of the Iraq War. In response to a question from a journalist about the possible role of Saddam’s Iraqi regime in supplying terrorist groups with weapons of mass destruction, Rumsfeld said:

“As we know, there are known knowns; there are things we know we know. We also know there are known unknowns; that is to say we know there are some things we do not know. But there are also unknown unknowns—the ones we don’t know we don’t know.”

What Rumsfeld meant was that ‘unknown unknowns’ should be taken as authority to take pre-emptive military action. Tellingly, as the writer Slavoj Zizek soon noted, Rumsfeld missed out the fourth term: the unknown knowns, the things we know but cannot admit to ourselves that we know; the repressed or disavowed things that allow us to continue with our fantasy of how we would like to believe the world is ordered. If the glitch is anywhere, it is here, within us, in the unconscious, in the things we will not accept that we know.

Rumsfeld’s omission of the unknown knowns was itself a repression. Of what? Of the very idea of the unconscious; of the idea that we are always at least partly governed by mental forces and wishes beyond our knowledge and conscious intention. Repressed and disavowed thoughts, the unknown knowns, fester and wait to make their unpredictable appearance. They may wait years but the unconscious, as Freud so often indicated, has no sense of time. Twenty years on, and one year after Rumsfeld’s own death. George W. Bush was making a public statement about Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine. "Russian elections are rigged. Political opponents are imprisoned or otherwise eliminated from participating in the electoral process. The result is an absence of checks and balances in Russia, and the decision of one man to launch a wholly unjustified and brutal invasion of Iraq…I mean… of Ukraine." Glitch. Bush winced self-mockingly, then shrugged, "Iraq too." (In any case, Iraq had used a lot of chemical weapons of mass destruction against the Kurds in the late 1980s. This is well documented, but political memory is short, and selective.)

The acute moment of the glitch seems to suspend time and intensify vision. Bush paused when he realised his slip, staring intently into nothingness until he regained some shaky composure and deferred to thinly ironic humour. When a glitch is recognised, the world appears to stop, and we stare, feeling a gap has suddenly opened up between the given world and its meaning. Hitchcock holds the shot of the reversing windmill. Pakula holds the shot of the taped latch. Weir holds the shot of Truman touching the painted sky backdrop. These suspensions are moments of recalibration, of mental scrambling to find a new explanation to fill the void, a new account of appearance, which appearance itself cannot supply.

In this sense, the still photographic image could well be the ideal way not just to represent the glitch but to fix and contemplate it. A photograph freezes and stares, offering no obvious explanation of what it shows, but an occasion for making appearance thinkable, contemplatable. Providing, of course, the glitch is not the photograph itself.

The following text was written by Taco Hidde Bakker for Foam Magazine Issue 65

The digital and virtual realms may bear the promise of perfection, of a seamless and flawless world, yet the opposite is true. Behind veils of perfection, and more often as part of the veil, imperfections show up. Technology is human, after all, and so is all its ‘glitches’.

Before I learned about the project American Glitch by artist duo Andrea Orejarena and Caleb Stein, I’d never even pondered the dictionary meaning and origin of the term glitch. Surprisingly, the word is rather young and comes from astronauts’ slang describing a malfunction (first registered in 1962 according to the Oxford English Dictionary). It’s a hitch or snag. As an intransitive verb ‘to experience a glitch’ means a setback, a malfunction, or for things to go wrong. A glitch is not unlike a bug, yet is rather something more mysterious, alluding to the unexpected and unprogrammable (glitch is sometimes described as an acronym for ‘Gremlins Lurking In The Computer Hardware’).

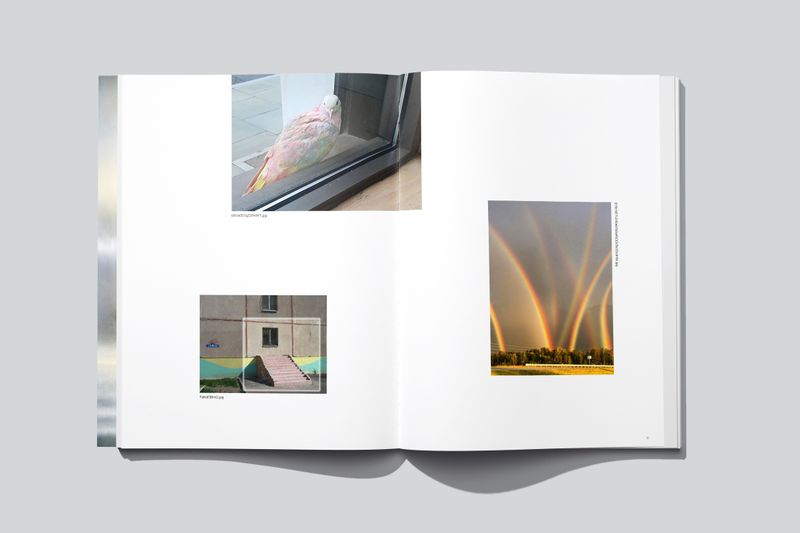

For Orejarena and Stein, the notion of glitch proves a fruitful framework for reflecting on many questions, not least on the ubiquitous medium of photography and its changing meaning and purpose in the screen age — where the ‘poor image’, in Hito Steyerl’s term, circulates in unfathomable quantities. They also wondered as to what registers as a glitch in a still image compared to the moving image? (In an essay in their eponymous book, David Campany reflects on glitches in relation to the virtual in American cinema.).

In a statement on American Glitch, the artists refer to the ‘ocean of information’ in which we’re living now, leaving us “perpetually asking what’s real and what’s fake”. The idea that we’re living in a simulation is becoming more popular. This notion “appears online where images are posted as personal evidence of spotting a ‘‘glitch in real life’’’”. Such ideas have been explored in popular films like The Matrix (1999) and The Truman Show (1998), as Orejarena and Stein point out.

For many years, several of them during Covid-19 -lockdowns, the artists have been exploring the World Wide Web (akin to ‘our collective subconscious’) in search of evidence of real-life glitches on social media posts and in Reddit -conversations. This search led to a large archive on the artists’ computers of threads and images, which became ‘“a place for a new form of community and connection across time and space’.

Are Americans living in a simulation and can proof to the contrary be found in the land (of mountains, deserts, forests, and farmlands) that ultimately delivers the raw materials that fuel our virtualities? As a way of placemaking — —adapting to their new homeland— the duo set out to travel by car the vast United States, to which Orejarena immigrated from Colombia and Stein from the United Kingdom, to photograph sites reminding them (or the conspiracists on the internet) of glitches in real settings. Could the artists find proof of all the wild theories they’d encountered in the virtual rabbit holes?

Some of the photographs they took on the road appeal to the tradition and grandeur of American landscape photography. Others are as surreal and mysterious as the imagery collected in Larry Sultan and& Mike Mandel’s Evidence (1977), which through its interweaving of science fiction, technological experiments, and catastrophe, questions conventional wisdom about photographic truth in the same manner as American Glitch, albeit before the internet and social media began complicating this even further.

The project continues the string of intriguing photographic-artistic views on the United States by outsiders (often duos as well), such as quite recently, for example, The Great Unreal (2009) by the Swiss duo Taiyo Onorato and Nico Krebs, whose comical and daring approach to the American landscape turned things upside down in their collages, in a satirical wink to the earnestness which often characterises domestic American landscape photography (think of the New Topographics).

Orejarena and Stein step into this venerable tradition (already by the plain grandeur of their title American Glitch, eighty-five years after Walker Evans’ American Photographs),as relative insiders, but coming to the landscape with their heads filled with glitches unimaginable to earlier photographic explorers of a United States that seems to become weirder by the decade., not least by virtue of all the (military) secrecy playing out in the backlands, visible parts, or remnants of which fuel an entire conspiracy business (such as speculation about visiting extra-terrestrials).

One telling image in American Glitch shows a pattern of roads in the desert in the shape of some Martian computer motherboard, as seen from the sky. Here, real estate speculation went awry, as the prospected suburbs never got built, and perhaps never will. The artists call it ‘the perfect suburban cul-de-sac’. I’m left to wonder as to what constitute the glitches here?

The following text is by Rica Cerbarano for the artist book, American Glitch, Gnomic Book. 2023.

I am not sure I should begin this text by quoting Jean Baudrillard. My argument might come across as predictable, obsolete, and hardly original. Yet, there is something that compels me to keep my eyes open to the connection between Andrea and Caleb’s photographic project and the words Baudrillard spent on the role of the image throughout his life. Like an opalescent reflection that lures and invites me to observe it with intensity, I can’t resist.

Is there still, on the edges of hypervisibility, of virtuality, room for an image?

Baudrillard wondered in The Conspiracy of Art, in 2005. In this age of fast-growing AI-generated images, developing metaverse and pervasive computational graphics, this is still perhaps one of the most formulated questions in the minds of those who are confronted—for work, passion or necessity—with visual aesthetics and its manifestations. Whether it is possible today to generate a vision where mystery, seduction and magic come together to trigger a jolt of energy, awakening a slumbering curiosity about the world in which we find ourselves living, is a question undoubtedly still relevant in our age.

For the French philosopher, the desire to photograph comes from the realization that the world, from the standpoint of reason, is a great disappointment; but taken by surprise, observed in detail and reconstructed from its fracture lines, the world reveals itself in its clearest clarity. It is the fragments that fit poorly into the construction of the simulation that make it stand out. The wrong piece in the puzzle is the one that makes us realize we are holding an object and not simply looking at an image made up of many pieces that fit together and dissolve.

I wonder: what are glitches, if not fragments of inconsistencies that break away from the conventional pattern of a representation? Imperfections that stand out to the eye, children of an unfettered rebellion that instills in the mind the possibility that what we observe is not exactly what it is?

But it is not only this, which leads me to associate American Glitch with the enlightening theories of Baudrillard. There is another curious commonality: in 1986, he published a book titled America, a sort of travelog that mixes together his journey aboard a Chrysler with sociological speculations on twentieth-century American society, told as the cradle of modernism and stage of appearances, the land where the hyperreality he so much theorized stood at its highest.

In Baudrillard’s recounting, America is rendered as that place where it’s no longer possible to trace a distinction between fiction and reality. There, the hyper-real world of simulacrum, where signs of the real have replaced the real, won the battle. Yet, Americans do not seem to recognize themselves truly as playing the leading role in the spectacle of simulation. The shop windows that mirror themselves show them exactly the image they aspire, reflecting completely the idea of how they should walk the street. The simulacrum is grafted onto them. They live the simulation with no glitch affecting their everyday acting.

In American Glitch, what emerges from the images taken by Andrea and Caleb is precisely that rift that makes the narrative of the truth shaky, on the verge of giving way. A crack that becomes an unbridgeable rut. As Baudrillard did, Andrea and Caleb embarked on a road trip across America and, as if to follow up the philosopher’s words, they went in search of those fragments of inconsistency that reveal the presence of a dominant system, [the] mismatches that make reality all the more real as bizarre and unusual. Magical and alive. Who ever said that reality is a rational thing?

Looking for cracks in the holographic wall of hyperreality, Andrea and Caleb ventured out on a journey that magnificently routed them in what is still considered today to be one of the major roles of the artist: collecting the interference of the magical in the real. Through American Glitch they are creating an inventory of metamorphic imperfections, [the] seductive simulations that are more real than real precisely because they do not adhere to the conventional rules of realness. Today, there is something more incredible than dreams: the possibility of shaping reality based on imagery that transcends the limits of reality itself. Andrea and Caleb have undeniably sensed it.