You told me I was beautiful

-

Dates2021 - Ongoing

-

Author

- Locations France, Spain, Lebanon, Egypt

This project explores the struggles of womanhood in the Arab world, focusing on the challenges that women—and I—face in defining our identity and femininity within a society where personal choices are shaped by external opinions and pressures.

Hello, my name is Laura Menassa, I am a photographer based in Beirut, and I am part of WomenPhotograph.

Over time, my camera has become a tool to discover and apprehend the world around me, while being able to maintain a certain distance. Being behind my camera makes it easier for me to interact with others — my way of questioning society and its disruptions.

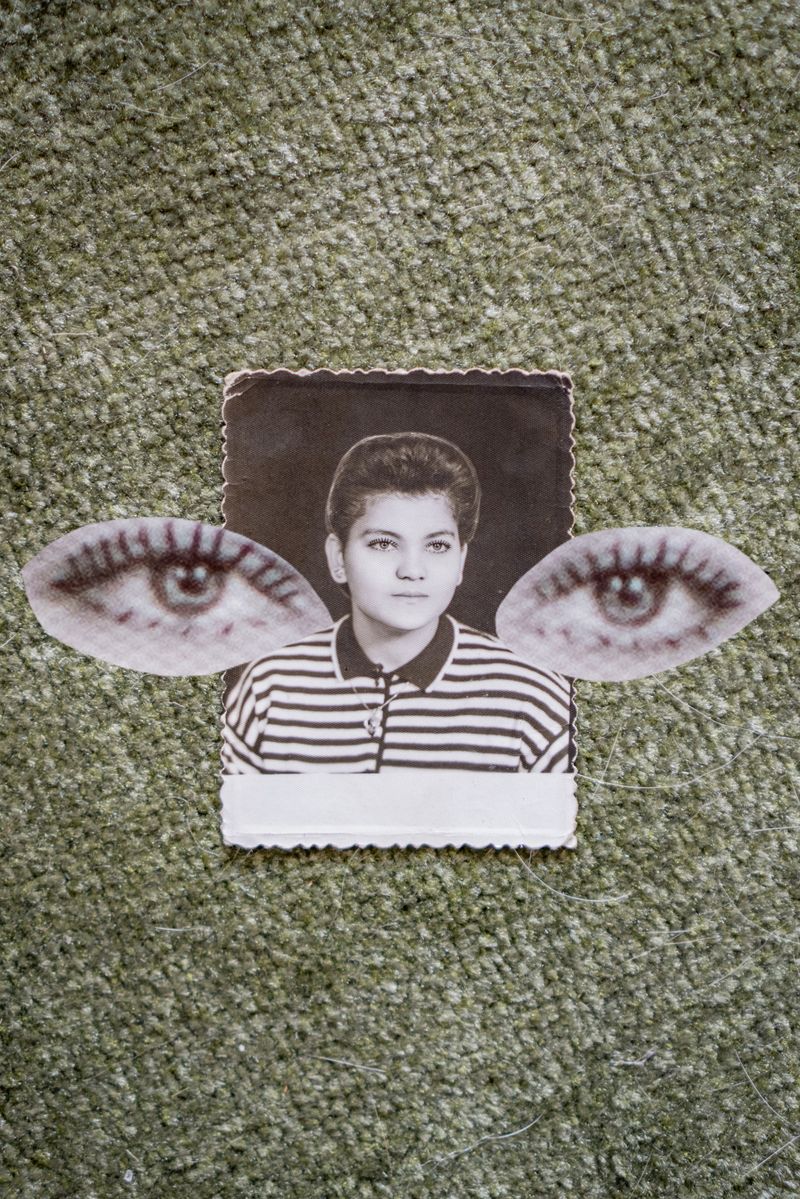

At first, I was documenting my personal life, my intimacy, or the one I shared with those around me. But I turned it toward the outside, expanding my field of discovery, navigating between personal and public spheres. And I liked to challenge taboos and perceptions around me, by examining the city more closely, my culture, but also my own body. The unseen or unspoken, are where I believe vulnerability becoming a strength. Then, quite a few questions began to surface, about identity, the body, territory, but also time.

------

If I had to define myself as a woman, I wouldn’t know where to start, as I don’t know where I belong, as I don’t know where I fit. From an Italian mother and a Lebanese father, I was born and grew up in the suburb of Paris, constantly questioning my identity as a Western-Arab—one who doesn’t look Arab enough, one who is considered French in Lebanon, one who is seen as the Lebanese girl in France.

These questions left me uncomfortable in my own body, as I was the opposite of the perfectly groomed Lebanese woman I had created in my head, and as I inherited features that didn’t associate me with a Western girl. So I decided to live in Lebanon in 2018.

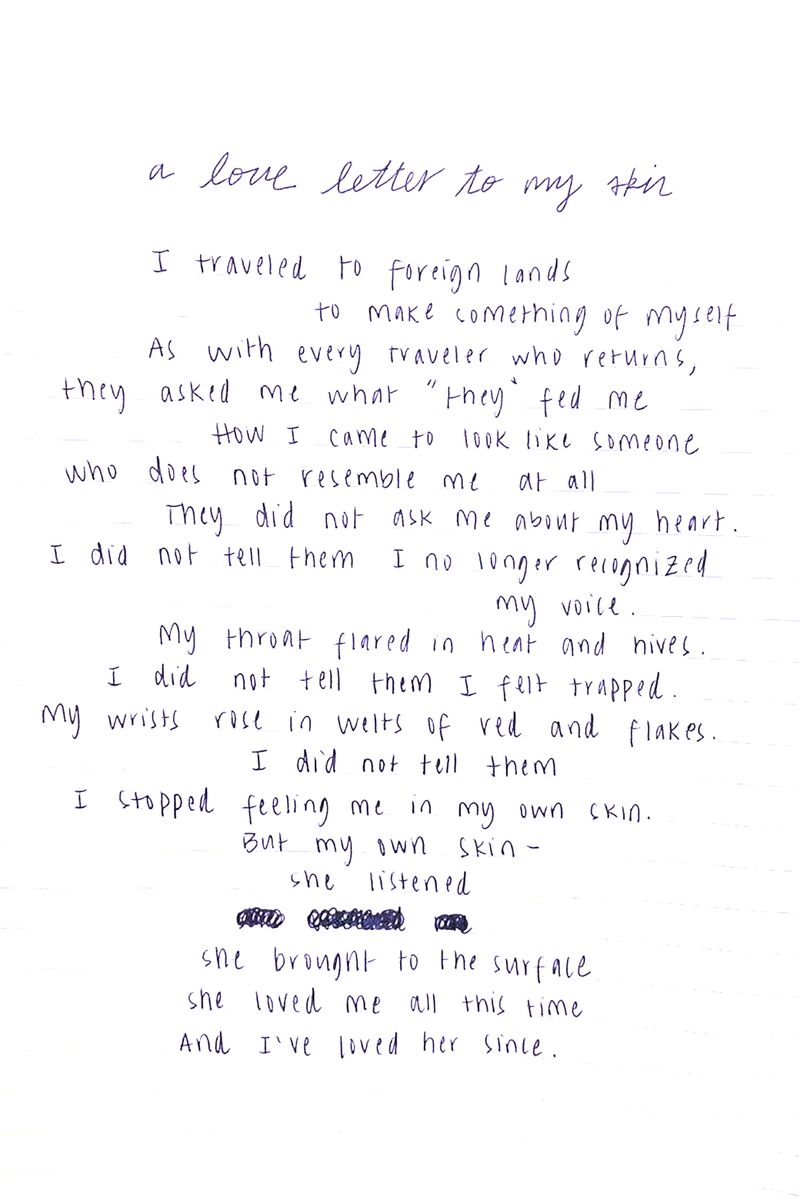

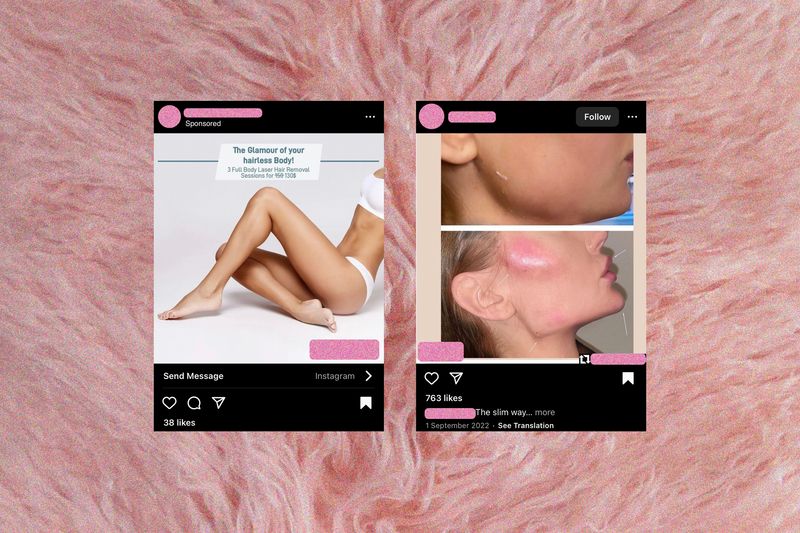

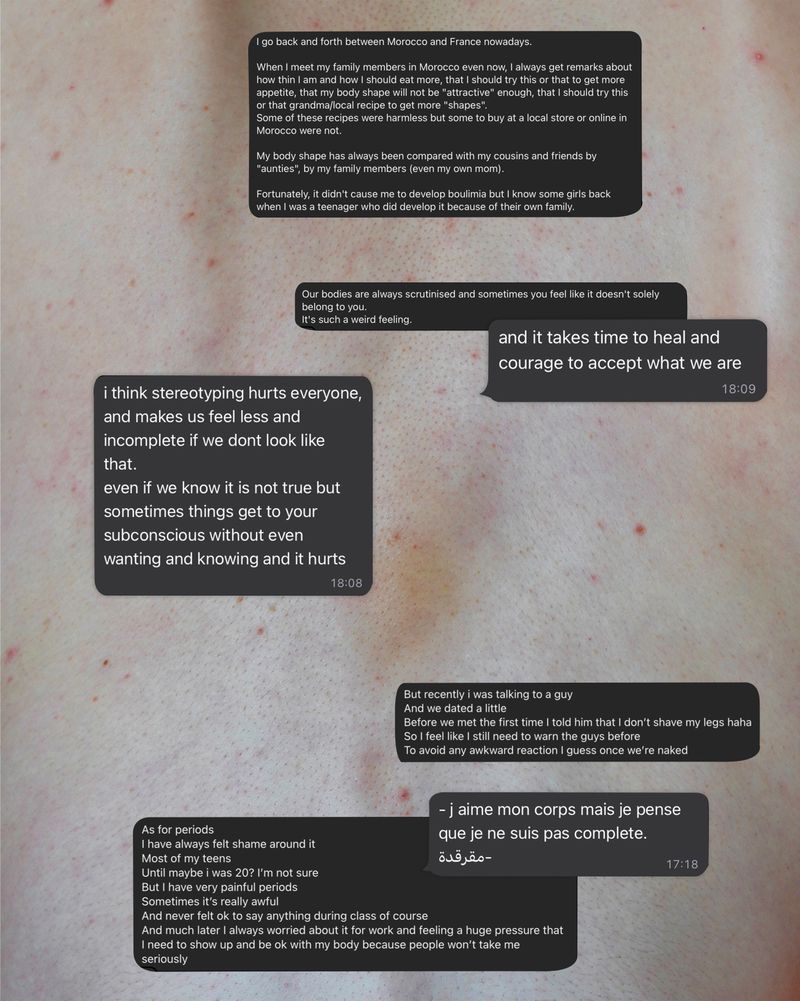

In 2021, while facing challenges in defining my sense of identity and femininity, I began questioning Arab women across Europe and the SWANA region on how they perceive themselves and their bodies, how they navigate beauty standards, and the influence of norms around them. Through many conversations, certain recurring and unspoken themes kept surfacing: judgment, shame around body hair, menstruation, discrimination based on skin color, intimacy, experiences of love, desire, and bodily violence, eating disorders, and a deep longing to feel at home in one's body.

The more women I met, the more I understood that the issue was never just about body stigma—it was the shame ingrained in our culture(s). What should be a personal relationship with our bodies had become a contested space, where external opinions dictated how we should look and be, where the male gaze dominates.

Coming from different countries, cultures, and backgrounds, sometimes with mixed origins, those women and I share common struggles in finding our place and fully embracing our identity as Arab women, while navigating expectations shaped by familial, cultural, and societal pressures.

Three years later, I realised this was not only about observing these women from afar, but about searching for myself through their stories. I had always had the privilege of living outside those rigid social structures, yet never fully escaped the shame they carried. Though I experienced life through a European lens, the wounds were still familiar, as if they were planted deep in our DNA. This project also became my way to reconnect with the roots I was born away from, shaped by my father’s migration during the Lebanese civil war. To hold the shame alongside these women, to understand it, deconstruct it, and slowly let it go.

From hidden wounds to quiet rebellions that shape womanhood, this project serves as a space where the act of being seen becomes a form of healing and resistance, a collective way to fight the rigid expectations and dismantle the taboos and shame around Arab women. Confronting the silence imposed on us and choosing to show, and to exist without compromising ourselves, is our way to reclaim our space and our bodies. To feel, even just a little, that we are not the problem, but rather the ones redefining what should have never been questioned in the first place.

Chronology:

My project began in Madrid in 2021, when I visited my friend Paula, who had suffered from anorexia and once lived with me in Beirut. We shared similar struggles and always encouraged each other to take care of ourselves. In Madrid, for the first time, we were able to share a real and nourishing meal together. Even though Paula has no Arabic roots, she became the starting point of this project.

Back in Lebanon, I began collaborating with Lebanese women, and later received a grant from the Goethe Institute in Lebanon and a Masterclass support from World Press Photo and Samir Kassir Foundation. As the war erupted at the end of 2024, I was only able to travel after the ceasefire, first to Egypt and then to France. In 2025, I repeated the same trajectory.

I have met in total, photographed, or gathered the testimonies of approximately 14 women. Mainly photography (portraits and urban environments, such as graffiti or billboards promoting botox or laser treatments), personal testimonies, writing, and collages. The collages are created from documentation I collect: old advertisements, archival material, and screenshots of social media ads that push women toward body consumption. The photographs were taken in France, Spain, Lebanon, and Egypt.

Every time I meet a new woman, a new topic shows up but my process remains the same: they have freedom over what they want to wear, where they want to be photographed, and how they want to be represented. For their testimonies, they are encouraged to write them down themselves to maintain complete control over their stories. I am currently only able to work in Lebanon, in the hope of receiving further support to meet the women I am already in contact with in Jordan, Morocco, Algeria, Saudi Arabia, and Europe.

In the long term, I wish for this project to become an educational book, mixing contemporary photography, personal testimonies, and historical and cultural components about the societal and political aspects of the diverse societies I am exploring, as well as the themes encountered. Two Lebanese women—a psychologist, and a writer, feminist, and activist—will also contribute to the writing.

Thank you!