Yoluja

-

Dates2019 - Ongoing

-

Author

- Location La Guajira, Colombia

A train comes and goes. It loads and it unloads. A loud sound announces the moment it arrives, it resounds and vibrates as if drilling into the memory of a promise. It’s roar is a symbol of a promise of progress that the residents of Medialuna are still waiting for.

The Pushaina family is from the indigenous community Wayuu, in the far reaches of northern Colombia. It’s one of the 15 families in the Medialuna territory affected by the company Cerrejón.

The mining company arrived here in __ cual ano__ with a plan to mine the bounty of coal families like Pushainas live on, and ship their bounty off to Europe. With them, they brought promises of change, work, and a better life.

But “progress” always meant something different for Cerrejón and the native people who have lived here for centuries.

The language the mining company speaks isn’t one that understands ancestry, spirituality and the importance of land for the people here.

And 35 years later, accepting the promises of Cerrejón have come to haunt the Wayuu.

On average, the company mines 6,300 tons per hour, sometimes reaching 11,000 tons per hour, which has gone on uninterrupted for decades.

These families know coal because they have lived with it. The dust is part of their skins, it cloaks their clothes that hang on lines under the scorching suns. It speckles the roofs of their houses and coats their lungs. Three families have been forcibly displaced from their native land, Puerto Bolívar, the very same place where coal arrives from the mine and is loaded onto ships.

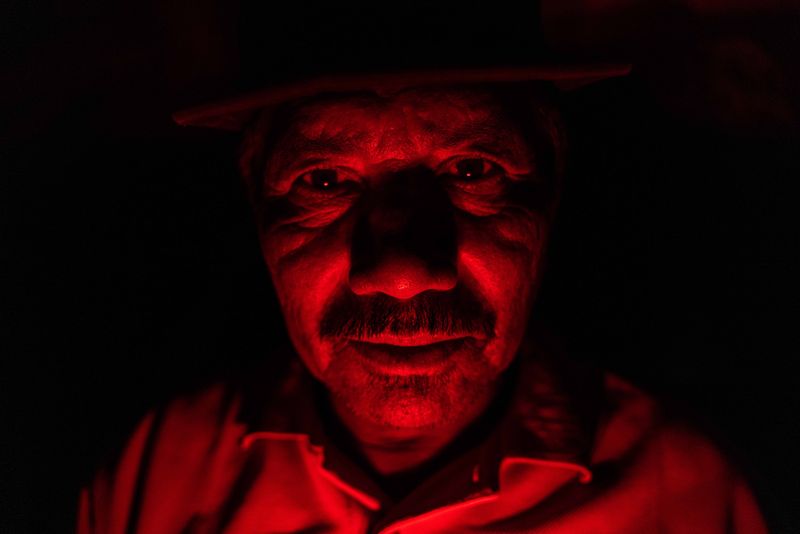

Today, that mine sits in a legal limbo in Colombia’s courts. And when the Wayuu people speak of Cerrejón, of the train, and the coal and the extraction in their native language, they use different word. Yoluja: devil, shadows, demon, and malice.

"The train that transports coal, in its cargo also carries spirits, they get off and torment us. They steal our sleep and a Wayuu who does not dream is because he has died. "It still hurts us, it is a general thought, what will happen when he leaves, we will be much better off without his contamination, the trees will grow again, even if it is bare for some time, the cactus will bloom again."