Valle

-

Dates2022 - Ongoing

-

Author

- Topics Nature & Environment, Social Issues

- Location Atacama, Chile

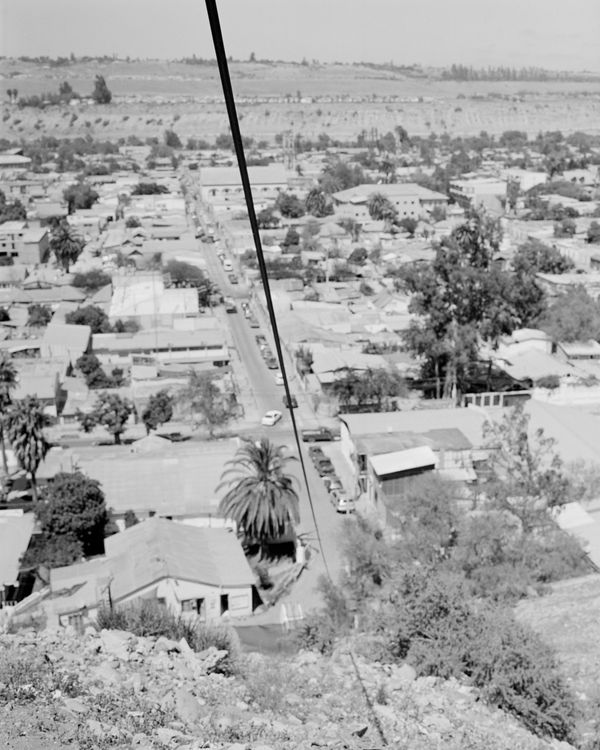

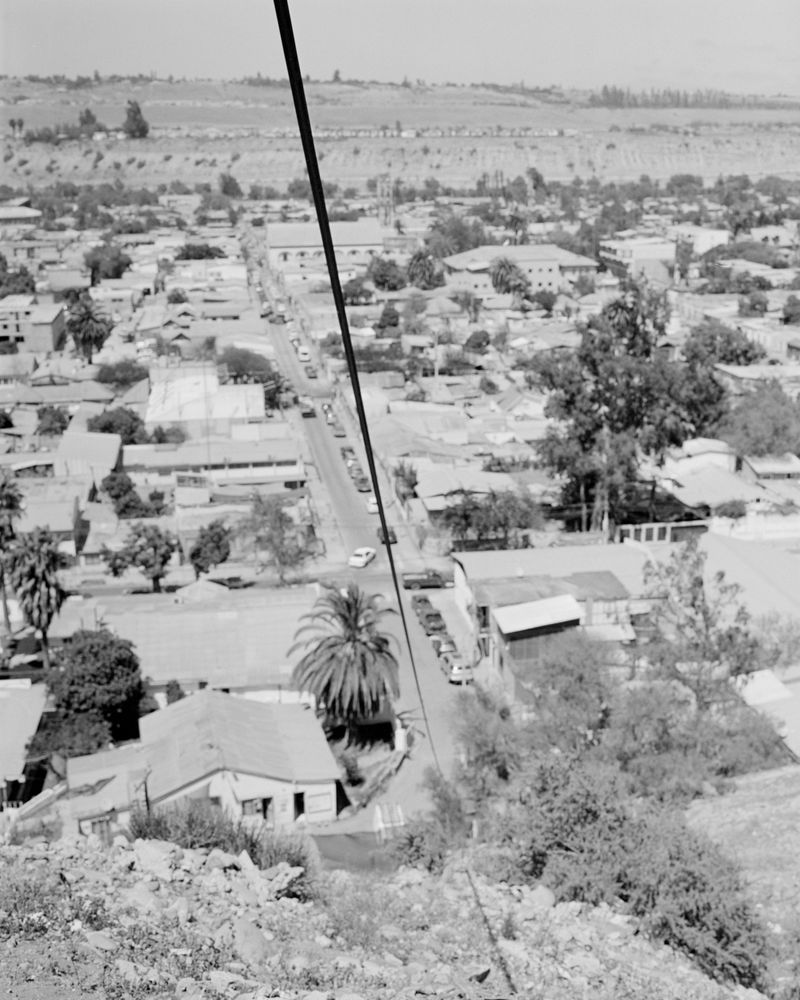

Valle is a project created in the Huasco Valley, in the Atacama Region of Chile. The work is an initial chapter of reflections on the different concerns of the communities in relation to their territories.

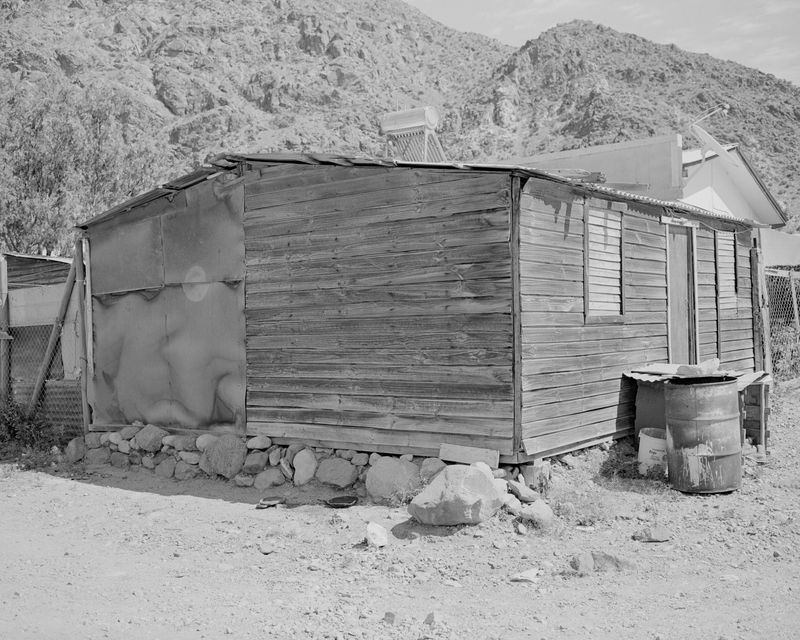

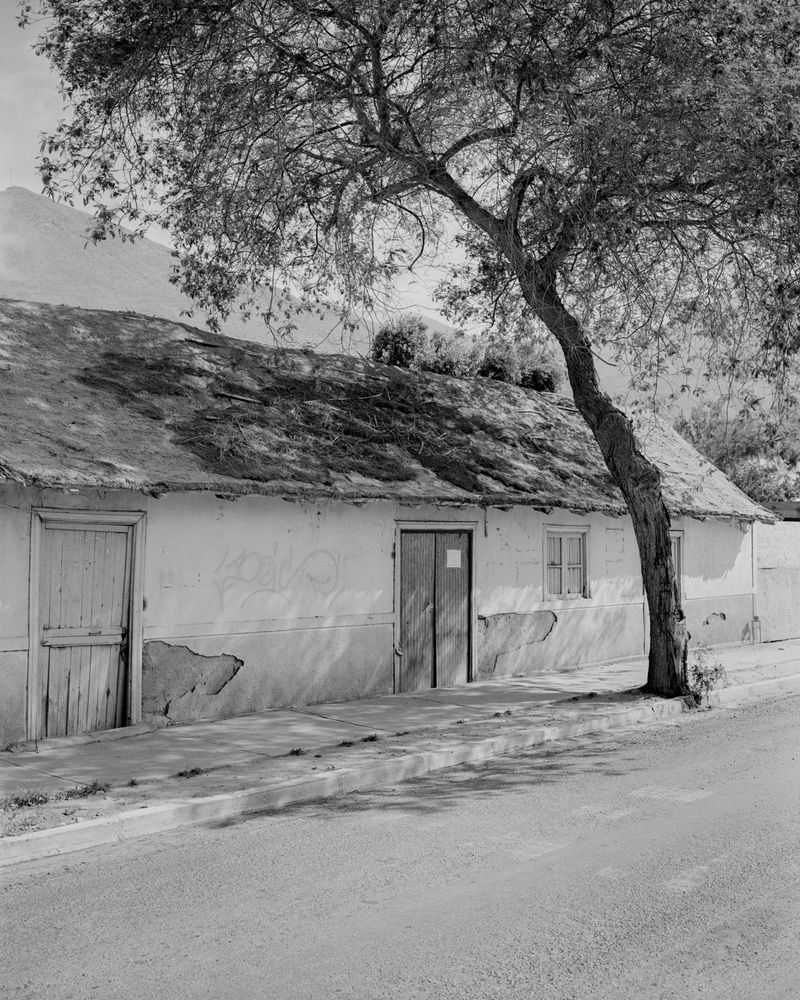

Valle was created as part of a research project in collaboration with Associate Professor, Eduardo Ordonez-Ponce, from Athabasca University (Canada). These photographs are part of a larger body of work that focuses on communities and their territories throughout the Huasco Valley, located in the southern Atacama Desert, Chile. Huasco is the last active valley before the world's driest desert begins, and a place which has been dealing with a variety of environmental, economic and health concerns for more than 30 years. The pictures reflect on concerns that have affected and continue to affect (for better or worse, depending on how you look at it) the life of the communities, the access to basic and universal services, the relationship with what development and the environment mean and represent in the use of this territory.

Accompanying the research team in a process of interviews and surveys throughout the valley, the work created from an author's point of view, also borrows techniques of documentary photographic practice. These black and white photographs are a record with a subjective perspective that was inspired by the studied data, the conversations with the locals, the beauty of the landscape, and human intervention in the territory as it has evolved over time.

—

Once Chile recovered its democracy in 1990, a remarkable process of western-style development (Moore, 1966) started based on an economic model that delivered macroeconomic progress (The World Bank, 2021), but which has left behind many communities across the country (Benedikter & Zlosilo, 2017; Fábrega, 2019; Siavelis, 2010). Just like many other of the so-called high-income countries, there are still communities in Chile living in poor conditions, despite the incorporation of Chile to the OECD in 2010 and the international recognition of the Chilean model of development (Richards, 1997).

The Huasco Valley is one of those places still left behind. Located in the south of the Atacama Desert and known as the last valley before entering the driest desert on earth, the Huasco river gives life to the valley, its people and their ways of living. The Valley is formed by four main communities (namely Huasco, Freirina, Vallenar, and Alto del Carmen) reaching a population of about 72,000 people distributed along 150 km from the Pacific Ocean up to more than 4,000 m.a.s.l. in The Andes. The main economic activities of the region, other than services, are by far mining (41% of the regional GDP) with one of the highest GDP per capita among regions in Chile (Instituto Nacional de Estadísticas, n.d.) but still with many unsolved socio-environmental issues (Environmental Justice Atlas, n.d.; Instituto Nacional de Derechos Humanos, n.d.), reflecting the inequality Chile still suffers . Although the Valley has been subject to the development of industrial and mining projects for years (Bolados-García et al., 2021), emblematic developments have been cancelled due to public pressure and the companies’ poor socio-environmental practices, despite being approved by authorities. These include mining, agroindustry and energy projects. Some of the identified impacts of these projects include high levels of heavy metals in children and local produce, intolerable odours from pig carcasses, pollution of the local sea by mining tailings and long-lasting sediments in the Huasco river (Insunza, 2015; Myllyvirta et al., 2020; Vargas Aceituno, 2014). As seen, academic literature, as well as NGO research, show vast evidence of the social and environmental impact of these projects in the communities of the Valley.

Under this troubling scenario of development, investment, justice and distrust, conflicts appear due to the unfair distribution of social and environmental ‘goods’ and ‘bads’ that threaten the health, livelihood and social identities of these communities (Scheidel et al., 2020). Industrial territorial interventions, while creating employment, paying taxes and benefitting the local economy, also bring negative externalities that affect people’s ways of living, they hardly distribute economic benefits equally, and governments usually behave unilaterally (Amengual, 2018).

This work focuses on those communities and their territories with the aim of understanding the rationale of development and the potential role that multinationals play in it. After visiting the Valley, talking to its citizens and photographing its diverse landscape from the ocean to the mountain, we found a sensation of uncertainty and abandonment, and our work reflects the visible and invisible, the ephemeral and permanent, the transformations, adaptations, relationships and the intertwined conflicts existing across the valley.

Text by Eduardo Ordonez-Ponce, PhD.Associate Professor, Athabasca University

Photographs by Cristian Ordóñez