To Lose A River

-

Dates2021 - Ongoing

-

Author

- Location Shahpur, India

The most frightening stage in any metamorphosis is when an obsolete form has eroded, but the new one is still a chaotic, pupal mess. Shahpur lies on that cusp. Shedding its past it faces a crisis of identity and loss.

“To Lose A River” is an intimate study of how time has enacted itself upon Shahpur, my village in Uttar Pradesh. This metamorphosis is most visibly recorded—and most deeply felt—through four entities: my decaying ancestral home, the dwindling Sambar population in this belt, the shifting course of the Yamuna, and my memories of my deceased grandfather.

The most unsettling stage of any metamorphosis is when an obsolete form has eroded, but the new one is still a chaotic, pupal mess. In many ways, Shahpur lies on that cusp. Shedding its past of riverine agriculture and a once-thriving ecology, it faces a crisis of identity and loss.

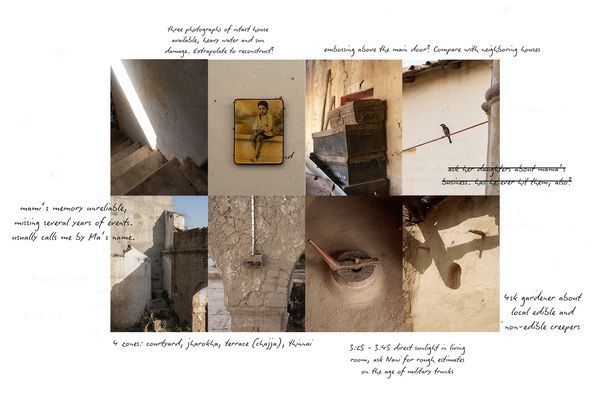

Part I: The Ancestral Home

How do two centuries of lived life vanish? Cracks creep into walls like tendrils, and bit by bit, as people leave a house, the house also leaves them. My crumbling nineteenth-century home in Shahpur stands as a casualty of rural outmigration, a phenomenon unraveling many social fabrics.

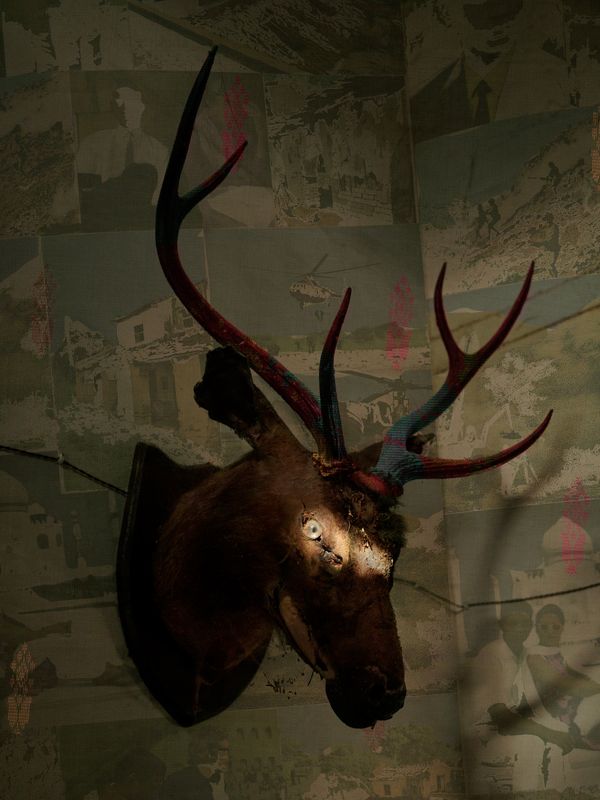

Part II: The Deer

It is not just humans who migrate, flee, desert, or die. The Sambar deer, a large and magnificent animal that once roamed the forests around Shahpur, is now a rare sight. Victimized by rampant industrial development, it too has found its old haunts uninhabitable.

When we do catch a glimpse of it, it is often mounted on a wall. The taxidermied deer head is not just a vestige of human cruelty but a relic of caste-based power. Since hunting was once reserved for the upper castes, an endangered deer became both a coveted trophy and a marker of privilege.

Part III: The River

The Yamuna cuts through Shahpur like an artery. A river that once watered crops, fed children, and offered cool respite in an arid place is now retreating—whether in fear or exhaustion. Villages like Shahpur have become repositories for toxic runoff, where the heavy displacement of soil reshapes the landscape in slow but undeniable ways.

As generations change hands in the village, they will not inherit the same river. Instead, they will inherit swathes of the exposed riverbed—evidence of unchecked development and an altered ecology. They must now grapple with the impossible task of finding new ways to enter the Yamuna, both physically and metaphorically.

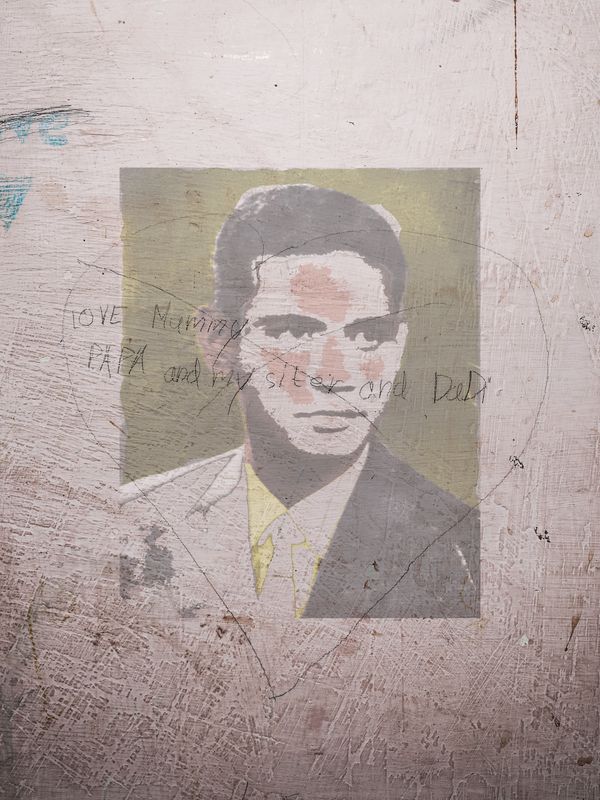

Part IV: Grandfather

At the center of this shifting landscape stands one figure, his memory becoming increasingly hazy. He anchors this project just as he once anchored our family and the social structure that held us in place. His legacy is militaristic, tinged with violence.

This is a deeply personal project—like any project about metamorphosis should be. It is mediated through the distortions of grief and the silence of lost stories, teetering between history and erasure.