Tiger's Blood

-

Dates2024 - Ongoing

-

Author

- Location Fayetteville, United States

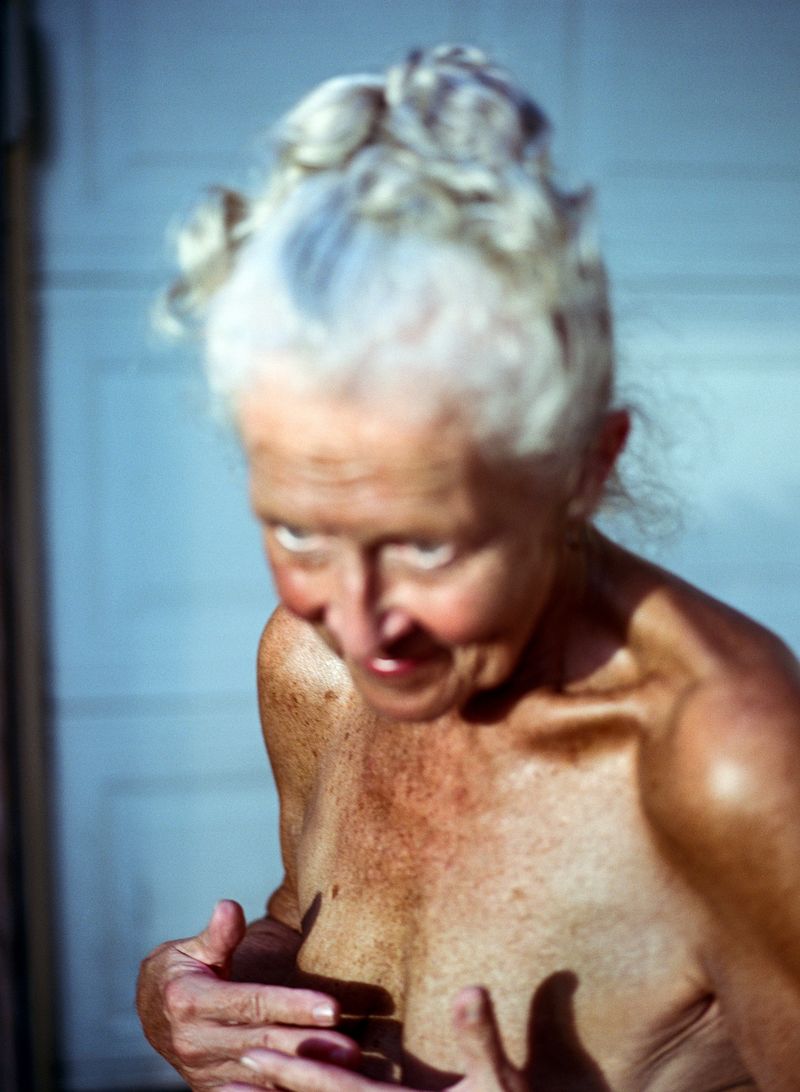

After training my accent into nowhere on a professor’s advice, I returned to Arkansas to photograph what assimilation costs: three generations of women, Snickers bar sermons on virtue, and Tiger’s Blood stains that won’t wash from white uniforms.

At a Waxahatchee concert in Red Hook, a band named for a creek in Alabama, I stood in a room full of people who had been grandfathered into taste. Friends of friends of the band. Fluent in references I didn’t catch. My ex had brought me along with his group, and I was trying to fit in, the way I sometimes did.

His best friend Skye was perched on an industrial trash can, drunk and swaying. When she started to slip, I caught her. Muscle memory from years of spotting, arms forming an automatic cradle. She laughed as I set her upright.

“Oh my god, you guys, did I tell you Chloe was a high school cheerleader?”

She drew out the last word like it explained everything about me, like it was the only thing worth knowing. I didn’t think it was a good punchline but everyone laughed, including him. Not cruel laughter, but the kind that draws a line, us and them, ironic and earnest, knowing and naïve.

Later, walking home, I played Waxahatchee through one earbud and asked if anyone knew what the album title Tiger’s Blood meant. No one bit, so I filled the silence, “It’s a snow-cone flavor. Orangey-red. The kind that stains everything. You only order it once.”

They didn’t know what I meant, and they didn’t ask. They’d never had to scrub that orange stain out of a white uniform in August. I was the one who felt like the punchline for having actually lived it.

\

My first semester at Georgetown, a professor pulled me aside after class. “You’d sound more intelligent if you dropped the accent,” he said, smiling like he was doing me a favor. “More dynamic. You’ll go farther.” I thanked him. I had only just learned what Vineyard Vines was, and I knew there was more to fix.

So I trained myself out of it. Clipped my vowels short. Swallowed the softness. Made my voice sound like it came from nowhere in particular. It worked. People stopped asking where I was from, but now I don’t sound like my Mimi or my Poppa, and I think about that every day.

Even with the accent gone, when I mention Arkansas, the follow-up is still sometimes about cousins, whether I plan to marry one, or if someone I know already has. The last time was at a baby shower in Manhattan a few months ago.

\

At another venue in Red Hook, the kind with church pews for seating, I found a Bible tucked behind a bench. I did what I always do when I find one, flipped to 1 Corinthians 1:11 and underlined my name. I had to read the whole thing twice to find it, years ago. You wouldn’t think Chloe was in the Bible, but she is.

I underline it because I don’t know what I believe, only what I don’t want to forget.

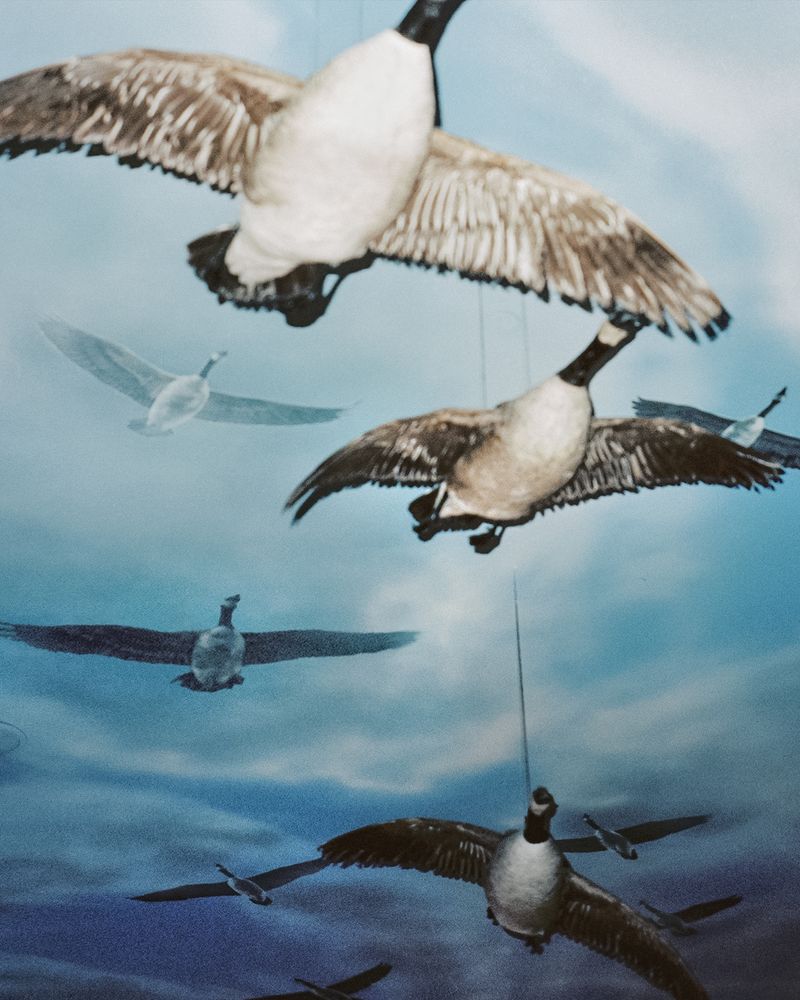

Since returning to Arkansas, I’ve been thinking about inheritance, about what gets passed down and what doesn’t. How some people inherit taste while others inherit stories and stains.

How easy it is to spend your twenties sanding down everything that makes you legible to yourself and the people who raised you, only to realize too late you’ve sanded off the meaning, too.

Memory works the same. Buff it too much and it becomes pretty and useless. Keep it rough and you get splinters, but at least it feels right.

At fifteen, a youth pastor told a room full of girls that our virtue was like a Snickers bar. “Nobody wants a candy bar someone else already took a bite out of,” he said.

“So why would your future husband?”

We sat silent, thighs stuck to metal folding chairs, while the boys played laser tag in the next room. I almost forgot that story until I started writing this. I almost lost the absurdity, the danger, the weird specificity.

But the Snickers bar? That’s mine. I earned it.

\

I didn’t start photographing my family because I thought it was important. I started because I was scared I might forget; the way my Poppa’s undershirts clung to him in humidity, the concrete turtle sculpture we always ran over with our cars, undercooked triple-berry cobblers we ate anyway.

I didn’t know yet that remembering itself could be subversive. That the possums, the pie crusts, the half-told superstitions could be proof enough. Proof that domestic life cuts deep. That memory distorts, but it doesn’t lie.

The places we’re from aren’t soft. They’re sticky and specific and sharp. They don’t wash out.

Maybe that’s the point. Maybe the stain is the story, the way Tiger’s Blood marks your mouth whether you want it to or not.