The Verdict: The Christina Boyer Case

-

Dates2013 - 2022

-

Author

- Locations Georgia, Utrecht

On 14 April 1992, shortly after 12 noon, 22-year-old Christina Boyer drove off to work in Caroll County, just west of Atlanta, Georgia.

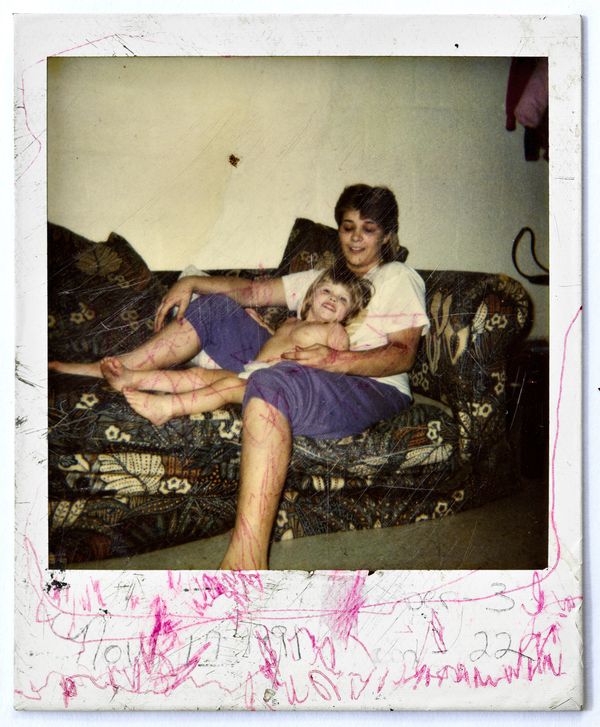

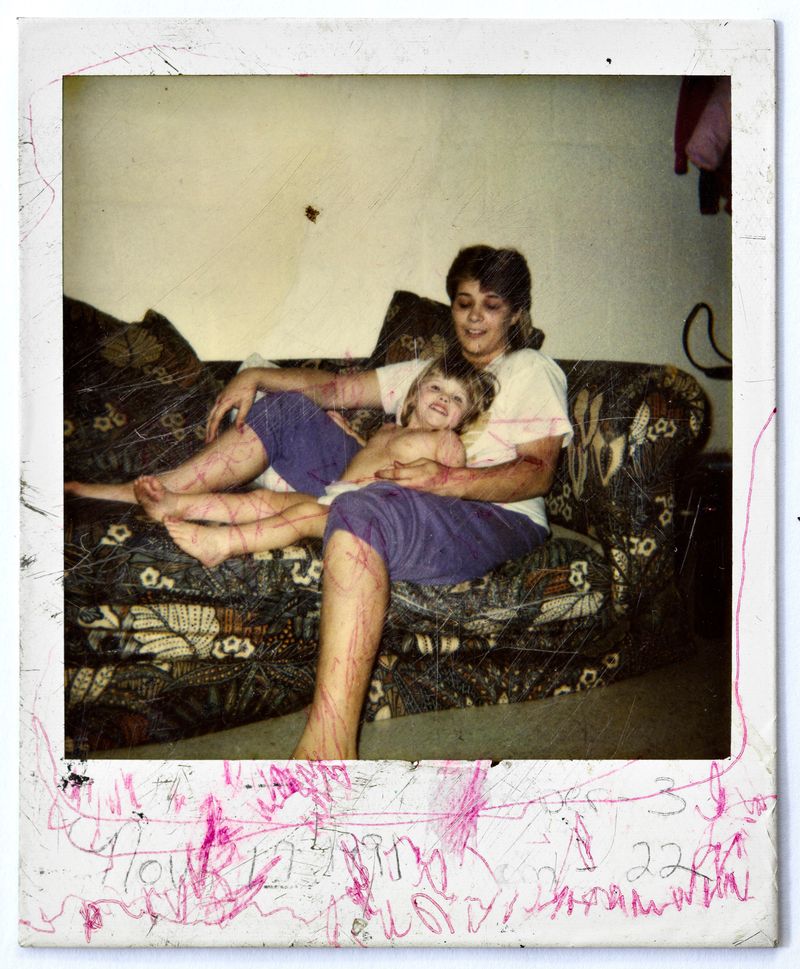

She left her three-year-old daughter Amber with her new boyfriend David, in his trailer. When she returned some six hours later, Amber was in bed – moribund. The three of them raced to the hospital, where Amber was pronounced dead an hour later. She had died of “blunt-force trauma of the head and abdomen” (and in particular the pancreas): according to the medical examiner, the result of severe abuse. David was arrested on the spot; Christina a day later. In the days before Amber's death, , the girl had suffered bruises and bumps. According to David, these were caused by falls. Amber had confirmed this, but it now turned against Christina as its was considered proof of her having abused her daughter.

As a recent transplant from Ohio, one who was a single mother and had appeared in a local, amateur porn video, Boyer could not count on much local sympathy or an unbiased jury.

Manipulation of facts and findings by law enforcement and contradictory statements by a forensic pathologist tainted the case. Several officials involved were of dubious character, as their later convictions for activities unrelated to the Boyer case showed.

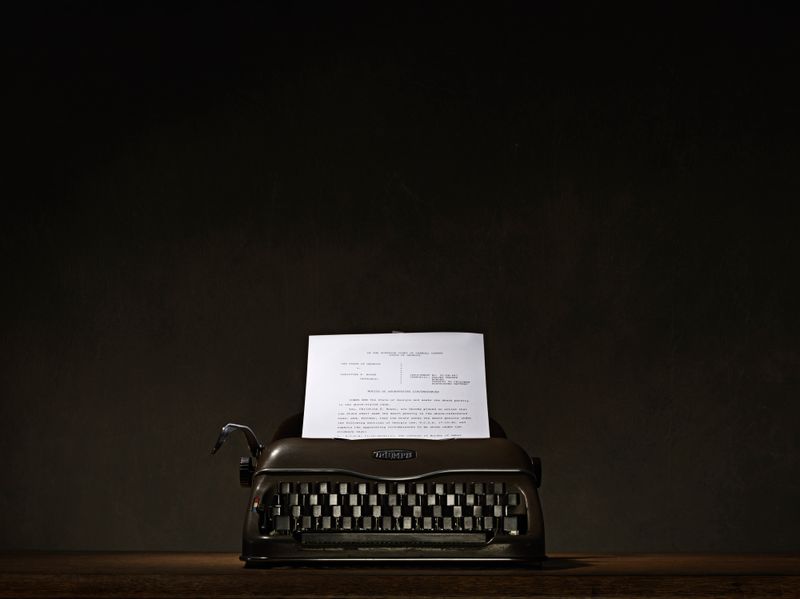

The prosecutor stated that he would be seeking the death penalty for both defendants, in spite of Christina passing a polygraph test answering “no” to the question of whether she had inflicted the injuries that caused Amber’s death. With this sentence hanging over her head and with little confidence in her court-appointed lawyer, as well as being under the influence of incorrectly prescribed antipsychotic drugs, Christina didn’t dare leave the case for a jury to decide, and therefore accepted an ‘Alford Plea’: a little-used form of plea deal which allowed her to maintain her innocence while accepting her sentence. The judge sentenced her to life imprisonment for murder, with an additional 20 years for severe abuse causing the injuries to Amber’s pancreas.

During David’s trial, a few months after Christina was sentenced, new information came to light that cast serious doubt on her guilt. First, testimony by the forensic pathologist in combination with David’s testimony, implied that if Amber had been hit on the head, it almost certainly would have happened during the last six hours (approximately) of Amber’s life – when only David was in the child’s presence. Many years later several European medical experts came to the same conclusion. On the basis of the autopsy report, the post-mortem photographs and the relevant witness statements, they confirmed that the fatal abuse could only have taken place after Christina had left for work.

In addition, during David’s trial, the forensic pathologist testified – contradicting his original autopsy report – that the injuries to Amber’s pancreas were not fatal and probably would have healed even without treatment.

David’s trial resulted in a conviction and a 20-year prison sentence for aggravated child abuse. He was released in November 2011.

In 2013, Jan Banning was allowed to spend three days photographing the inmates of Pulaski State Prison. While searching the internet for more information about the 80+ women he portrayed, he came across the story of Christina Boyer. Over several years, via email, a friendship developed.

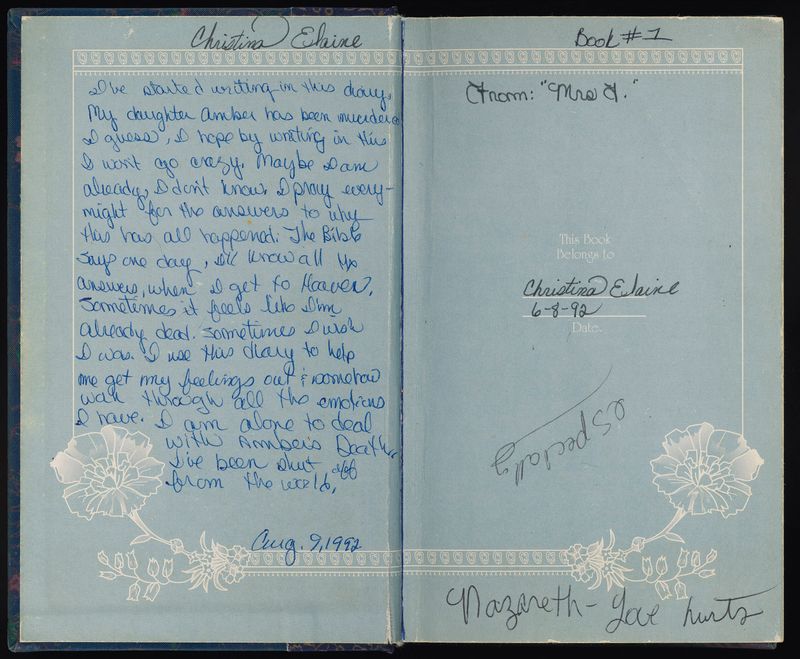

Assisted by Christina, Banning – who trained as a historian – gradually built up an exhaustive archive, including autopsy reports, post-mortem photos, police interview reports, court transcripts, psychiatric reports, Christina’s diaries and letters, et cetera. The deeper he dug, the greater his doubts about Christina’s conviction became. He got others involved, such as students in Marc M. Howard’s ‘Making an Exoneree’ course at Georgetown University. They concluded that a police inspector had created a web of untruths and wild exaggerations to ‘prove’ that Christina had displayed a pattern of child abuse; an accusation dismissed as unsubstantiated by child protective services in Ohio.

In spite of the strong indications of her innocence, Christina is still in prison, more than 30 years after her daughter’s death.

This case contains many ingredients typical of the criminal justice system in the USA, world leader in incarceration, with some 700 prisoners per 100,000 inhabitants (the figure in Banning’s home country, the Netherlands, is around 60).

In the state of Georgia, one in thirteen adults is under the supervision of the justice department, in one way or another. Some important aspects of the mass incarceration: (often elected) prosecutors and judges are under great pressure to be tough on crime, on the basis of a belief – long discredited by criminological research – that severe sentences act as a deterrent to crime. In addition, trials, particularly those where the death sentence is on the table, are expensive. They are a big drain on government funds. Indigent defendants often avoid the confrontation with a jury owing to a lack of faith in their (usually overworked and often miserable or unmotivated) attorneys. The result of such pressures is that 95% of criminal cases in the USA do not end up in front of a jury, but in a plea deal. The most reliable estimates conclude that at least tens of thousands of the prisoners are innocent.

The Verdict: The Christina Boyer Case is the results of Banning’s extensive and years-long research. In it, he combines documentary and staged photos, and makes use of light used in film noir, which he considers appropriate because of the moral ambiguity so common in that film style. Banning offers an intense account of the events surrounding Christina Boyer’s conviction following the death of her young daughter.

In his book “The Verdict: The Christina Boyer Case”, Artivist Banning also describes the critical interpretations of renowned medical experts, severely criticizes the role played by the media, and gives his own visual interpretation of elements of the story. The book is given extra breadth and depth through Banning’s decision to invite the ‘subject’ of the project, Christina Boyer, to make her own contribution by, for example, allowing him to share pages from her diaries.

Besides the book, Banning also made an exhibition. It was shown in the Dutch national photo museum NFM in Rotterdam and garnered much acclaim.

He now tries to use book and exhibition to influence decision makers and is presently involved in talks about exhibiting the work in the US. In the Spring of 2023, a three-part documentary about Christina Boyer and Banning and other supporters will be streamed by Hulu.