The Navel of the Dream

-

Dates2023 - Ongoing

-

Author

- Locations New Paltz, Sweden, Rhode Island

“The Navel of the Dream” describes a state of groundlessness. In this body of work photographs act as thresholds between what is seen and what is felt, between daydreams and nightmares, and between memories and myths.

In these images I have returned to the countryside of southern Sweden where I spent my childhood summers in order to investigate notions of belonging and rupture. From Sundsvall to Skurup my matrilineal family has occupied this land for generations. I lay claim to these groves of birch, spruce and pine, the brackish water of the Baltic, and the real and imagined landscapes that have contributed to my ideas of homeland.

By photographing my mother’s motherland, I hope to contribute to a developing lineage of mothers and daughters navigating grief and aging. In these images I honor my impulse to return while acceding that there is no way back. The landmarks remain, but the terrain has shifted and I have changed. Do I belong to this land too? Who possesses the landscape that is embedded in my dreams?

In this body of work, the landscape functions as a stage for engaging with loss; as well as a refuge, a backdrop for my subconscious, a mirror, and a body. I am interested in how emotions (and grief in particular) are implicated in people’s relationships with landscape. In these images I am looking at an exterior, but pointing to something buried within.

I began this project in earnest in December of 2023 while home on winter break and visiting my mother in Southern Sweden. I came equipped with a list of mental images that had risen to the surface of my consciousness, waiting to be realized. In a 2005 red Volkswagen Polo with my mother and sister, I set out in search of these compositions. We drove through the winding country roads with my gaze fixed on the horizon. Every so often pulling off onto the road’s thin overgrown shoulder so that I could photograph the bleak winter landscape.

In these images, the fields lay in anticipation. Sowed, tilled and harvested, the clay-heavy soil is densely compacted by rain. Only the occasional hollow stalk of last summer’s harvest remains. Seas of wheat, barley and safflower are at once a memory and a premonition. I see myself reflected in the dormant landscape, waiting for life to return. In my images ‘winter’ represents both the coldest, darkest season of the year and as a season of prolonged interiority.

Our bodies, and the land are timekeepers with their own circadian rhythms. I grew up measuring time by harvests in the center of an agricultural community. My summers were bookmarked by fertilizing seasons when the house would fill with the pungent scent of manure, which lingered for several days until the winds shifted. In late July tractors would slowly snake their way through the fields towards the house, stirring up clouds of chaff and bone dry top soil. By the end of August colossal mounds of sugar beets would pile up on the roadsides and the fields were dotted with bales of shrink wrapped hay.

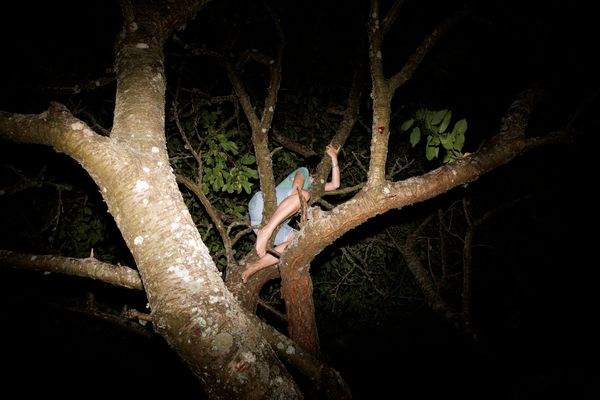

In my photograph “In the Cherry Tree” I am a faceless figure with sticky palms, gripping the craggy bark of a cherry tree. My knuckles whiten as I cling to its branches. In the dark, the flash and the facelessness of the figure make the image unsettling. It is incomplete - something half there. The spiny tree reaching wildly into oblivion is a ship in the night, a mast or a mooring for the untethered figure. A rich reddish amber sap pools and runs down the tree in the harsh white light. One summer my father sent me up the tree with a paring knife and a glass jar to dig nodules of the hardened, syrupy resin out of the branches. It oozed like blood from the bark’s gnarly crevasses and I remember how the residue clung to my fingers for days afterwards.

What is between me and the performance, what is that thing? Usually it is sadness. In this composition, the tree is more self-aware than the person in its branches, the cherry tree looks back at itself under the bright light of the flash, as the figure shields her face. In these landscapes, as well as in my interiors and portraits, I have used photography as a means to explore absence and an attempt to resituate myself in an environment that once knew me. In my own depictions of the land, feelings of fracture and unease bleed into the compositions. My gaze makes the landscape strange. By imaging the fertile, agricultural fields of Skåne in a state of dormancy, I upend the expectations and mythologies of the land. Pointing to surfaces of slowness I suspend my encounter in time.

What happens after a rupture? What is remade and what is undone? Where does the dust settle? Everything is different and I am responding to the shifting tide by searching for a place to stand. I use photography to reenact the mythos of childhood, and the deep waters of my subconscious. As I make the image, the image in turn makes me. My images are simultaneously mythmaking, and truth-seeking. I am actively attempting to define, and locate myself within their periphery.