the massif

-

Dates2015 - 2016

-

Author

- Topics Landscape, Documentary

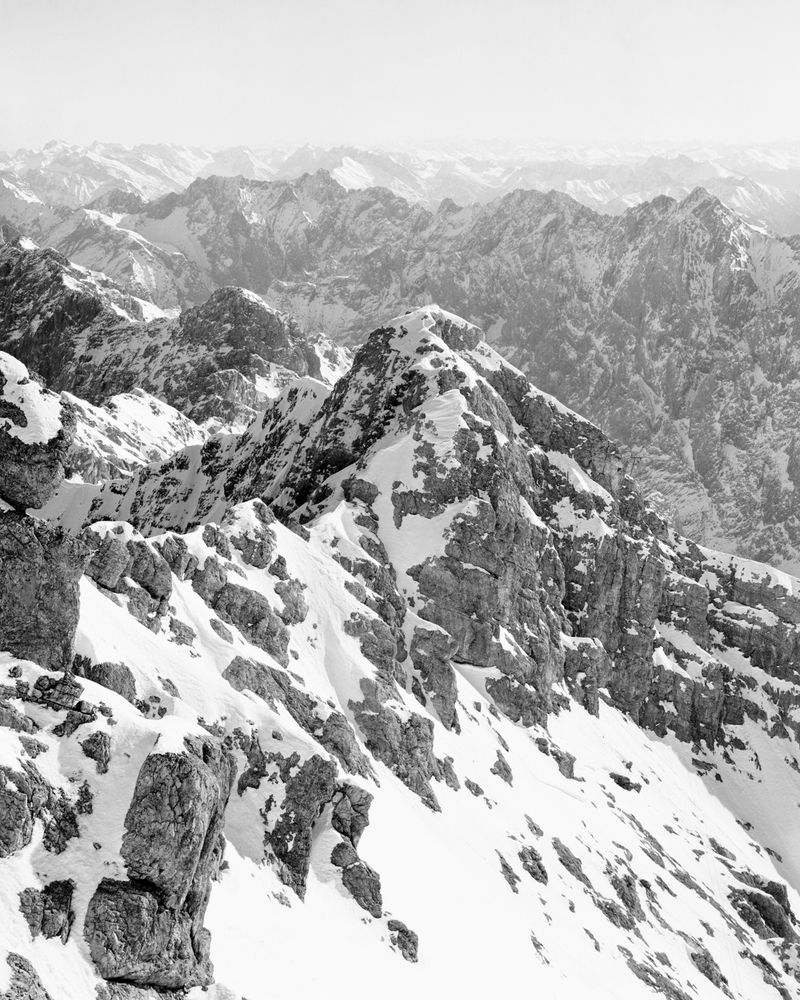

The experience of landscape has, for a long time, been nourished by an aesthetic view and an idea of landscape, storing up images, which are not pictures of nature, but figures of our imaginative construction. "The massif" shows landscapes of the anthropocene and questions our faculty of perception.

Exposé: "the massif"

Head for the mountains, into the wild! The primordial, limitless majesty. Seekers of the relentless forces of nature, pure and pristine - can be found there. Will they find what they sought?

Nature is “that, that exists by itself”, wrote german philosopher Gernot Böhme. Indeed nature itself created the mountains' unfolding, shifting and eroding. These are conditioned by the elements, plate tectonics, wind, rain, coldness and sun. The elements seem to have warred against the mountain; rains have washed, lightening torn, and the winds make it the constant object of their fury.

As beholders we yearn to experience nature unmodified, to leave civilization behind. Yet with every encounter the natural state and our perception of its naturalness is altered, transformed and even eradicated. That artificiality – deplored as a loss or glorified as a win – provides the condition for new myths – the myth of the civilization as the antagonist of nature. But a new myth not only takes the place of the old one, the old concept of nature nests like a residue in the modern comprehension, and landscape turns into an image, into a sign.

We do yearn for limitless freedom but only if it is safe. One acclimatizes to seeing the mountains with their artificial additions. Our image of a summit includes a summit cross, our slopes are framed by avalanche barriers.

Do we even consider these additions to be invasive? Are they not an integral part of our natural surroundings?

The experience of landscape has, for a long time, been nourished and formed by an aesthetic view. The idea of landscape, storing up images, which are not pictures of nature, but figures of exoticism. The appearance, especially the aesthetic component of landscape, is attached to a physical entity of which we are a part.

Do we emphasize the barrenness and wilderness of the landscape? We might glorify mountains or doom them. Parallels of the imaginative construction and actual representation of landscape blurs. Perhaps it unsettles us to stand before the unmoving mountain side, bare rocks without man-made memorials.

Nature is no longer just naturally occurring, rather it is formed,leveled and stabilized. These interventions influence how we perceive the natural state of the mountains. Its aura is diminished, transformed and redefined. Man-made devices supplement the natural order, changing and to some extent overruling it.

These images depict a general conception of the mountains' aesthetics and how human impact affects them. Observed discerningly the disparity between the natural-born mountains and the overextended civilization becomes apparent. As well as the need for a new word that encompasses the artificial, technical alterations.

Wilderness and unreveleshed nature are an essential part of the European history of civilization. Greek philosophers acclaimed natures beauty – a divine world order. The concept of landscape emerged within the beginning of the 15th century and culminated in paintings and literature of the Romantic period as the epitome of glorification and longing. Determining aesthetic norms shifted: from constant, typical and regular to variable, individual and irregular. Beholders contemplated nature in «delight and disorder», establishing an idea of nature that lasted until today – primordial nature opposing secure civilization.

«The massif» questions our ideals and ideas of nature. There is the bivouac, the shelter which serves as a refuge in the event of a sudden storm. The mountain pass that opens up formerly impenetrable terrain. Dams and barrages are built to utilize the power of the mountains, to tame the torrential streams and harness their energy. Barriers are erected to protect from avalanches and rockfall, the unforeseeable fragility and brutality of the massif's incline. What we see is a new form of landscape and era – the anthropocene.

The deliberate decision to use large format black and white 4x5 inch negatives derived from being forced to work slowly and consciously of my surroundings. Documenting landscapes, hence documenting the current reality is a subjective process, influenced by social, cultural, political and environmental factors. Changing between panoramic sceneries and close ups is supposed to demand and bewilder, to question ideas and ideals of nature. Nature appears in divers ramifications: human tracks in form of imperceptible paths through snow, as harsh incisions – graphically shown als sharp lines and straight edges. Formations and figures of nature, emphasized through the black and white of the photographs, questions yet again the remembered perception of the beholder. Spotting 'errors' in that monumental landscape, since Petrarca has described and John Ruskin has photographed it. «The massif» depicts a subtle though critical point of view aligning in the tradition of the New Topography movement.