The burden of freedom

-

Dates2023 - 2023

-

Author

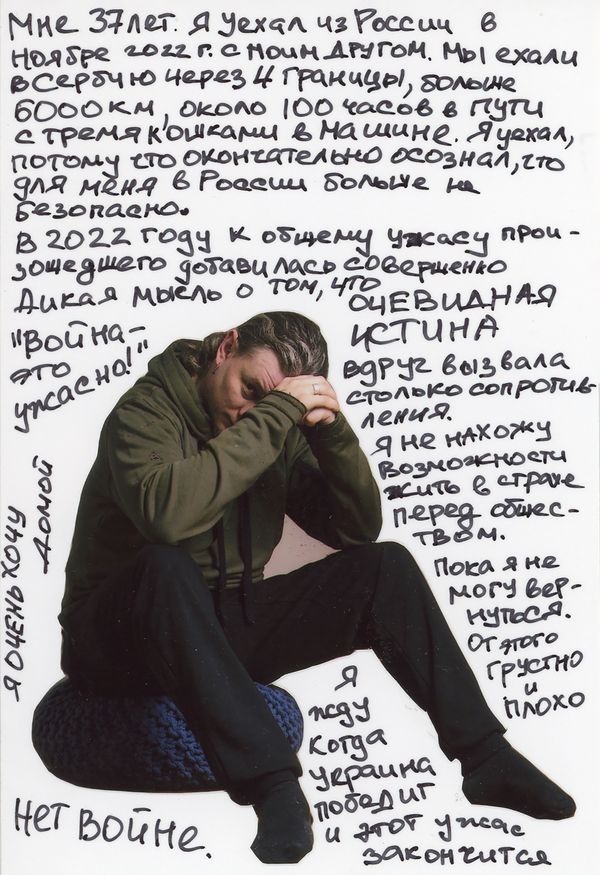

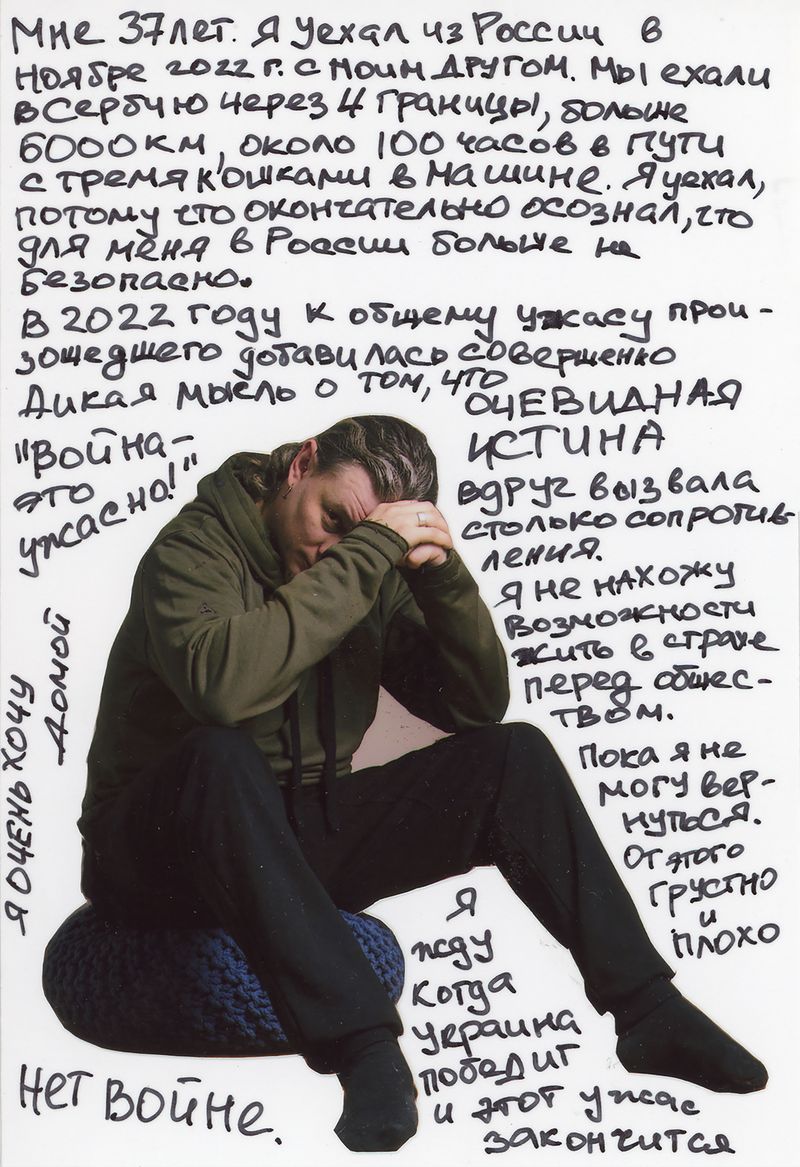

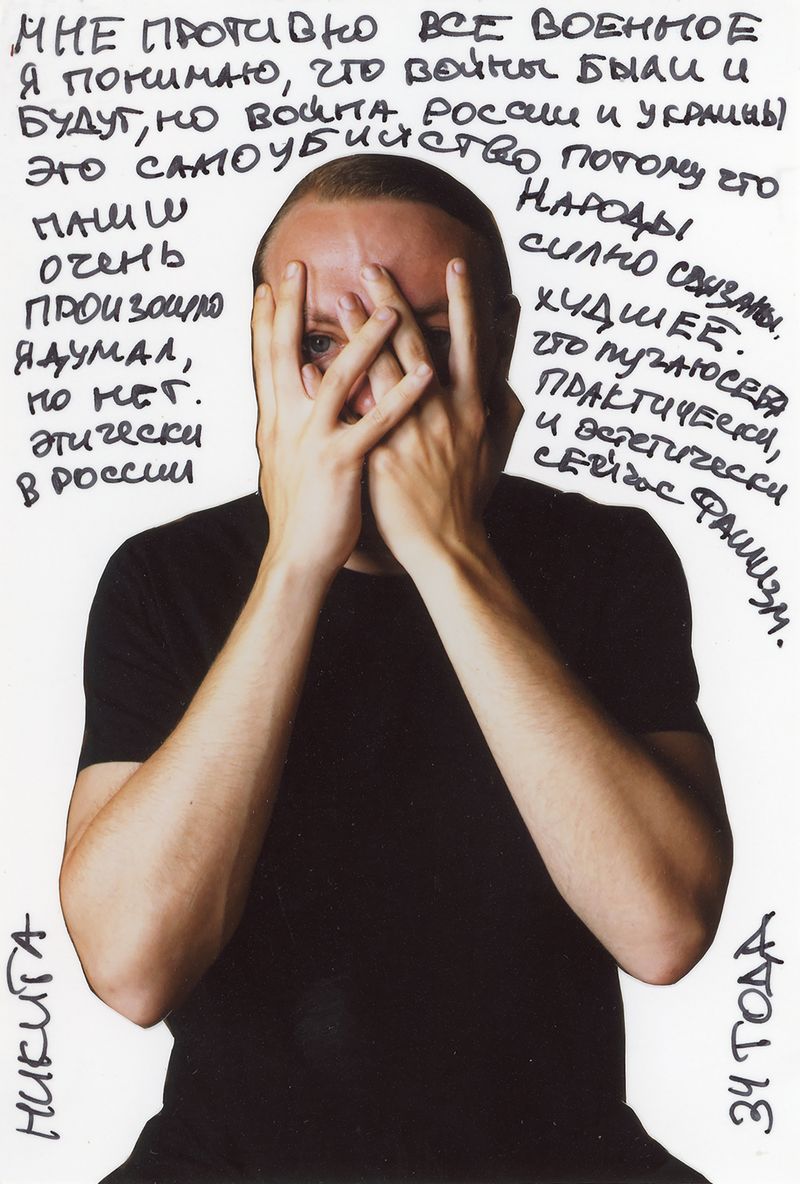

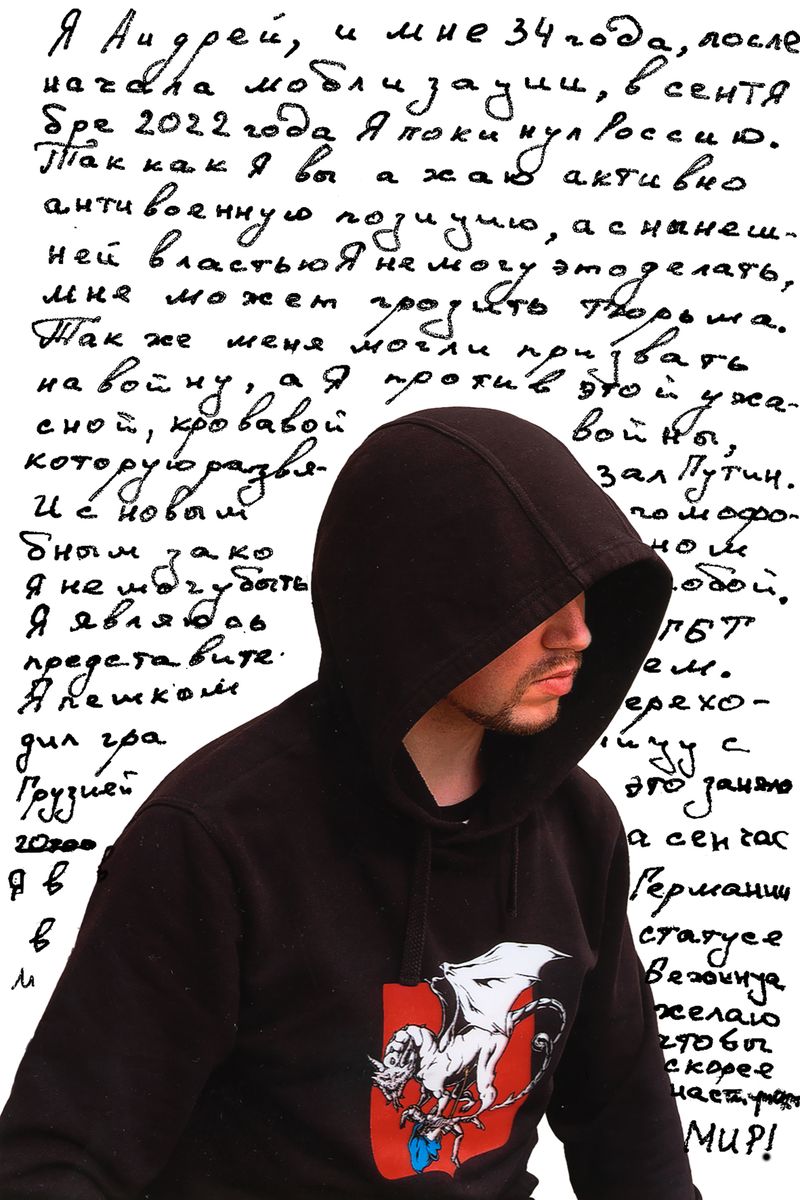

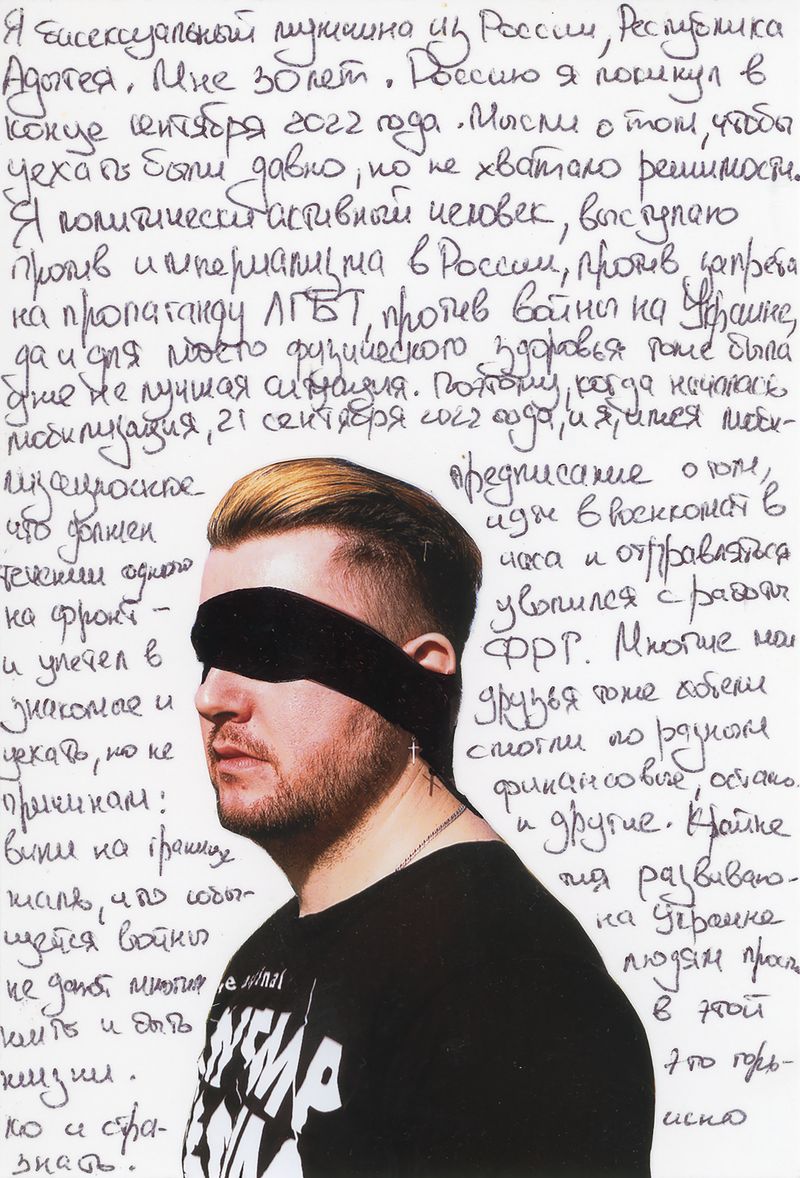

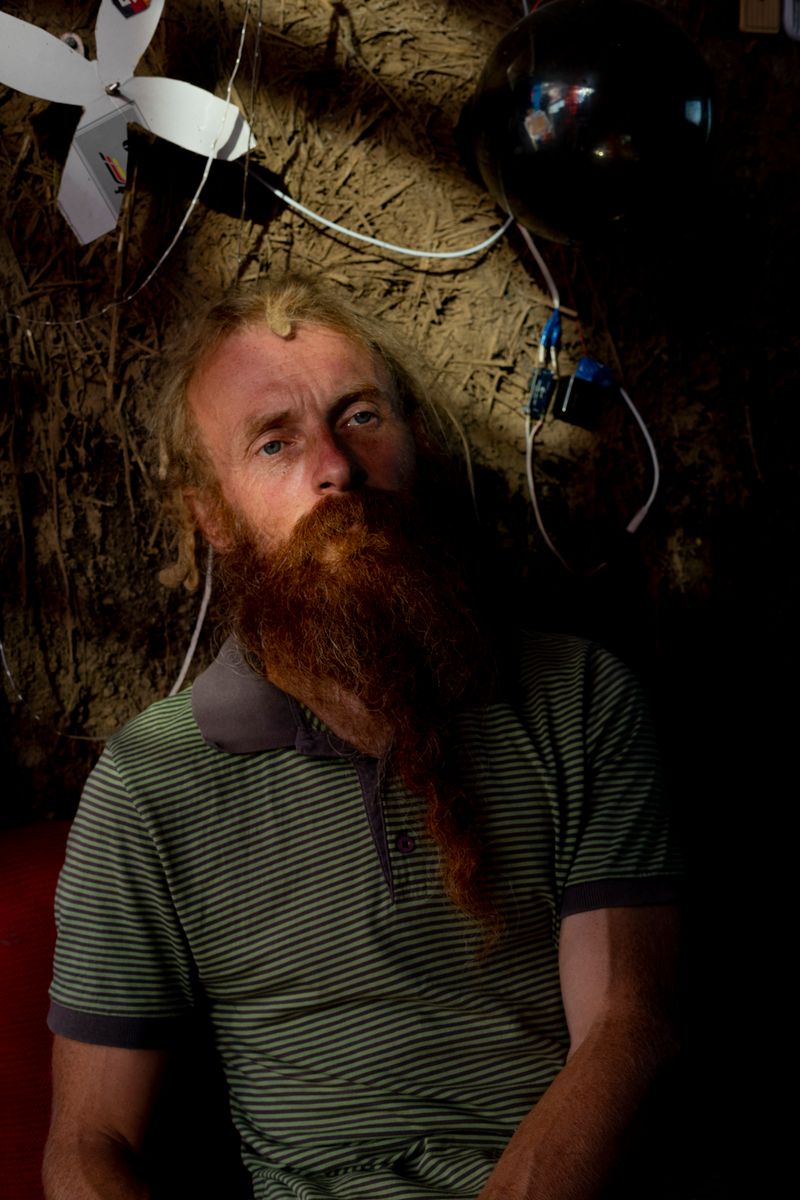

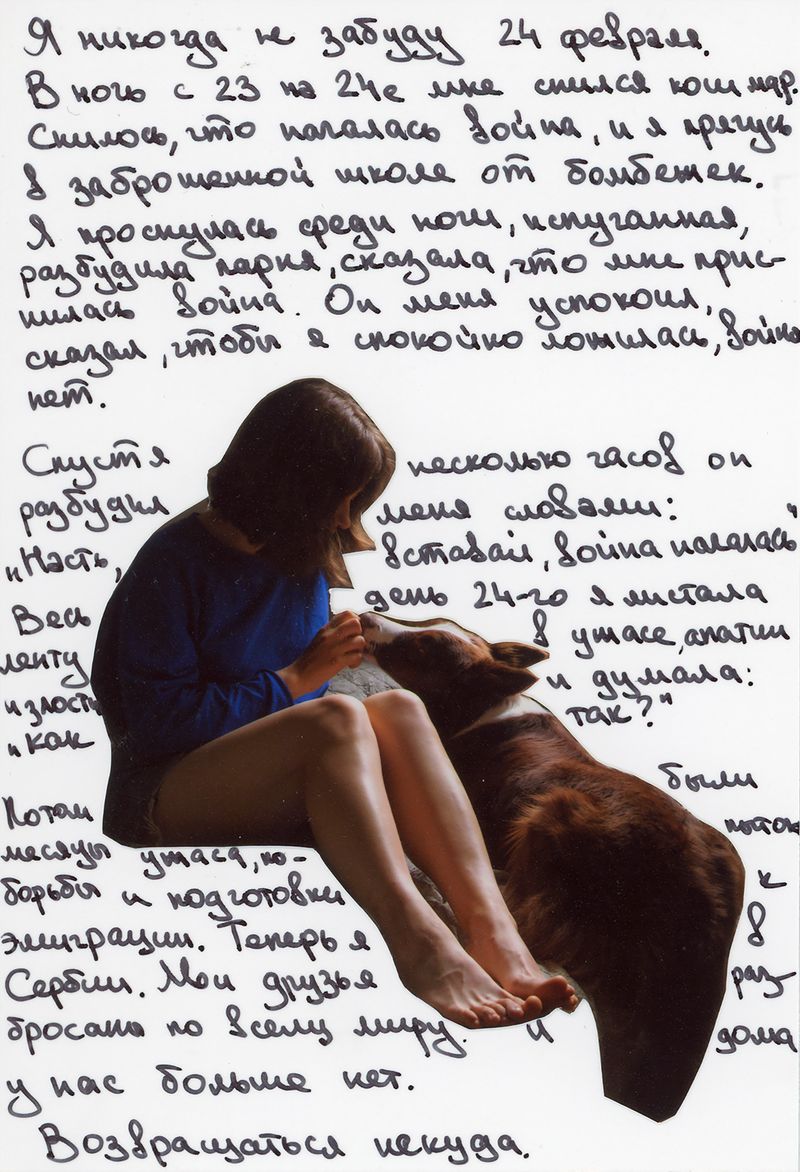

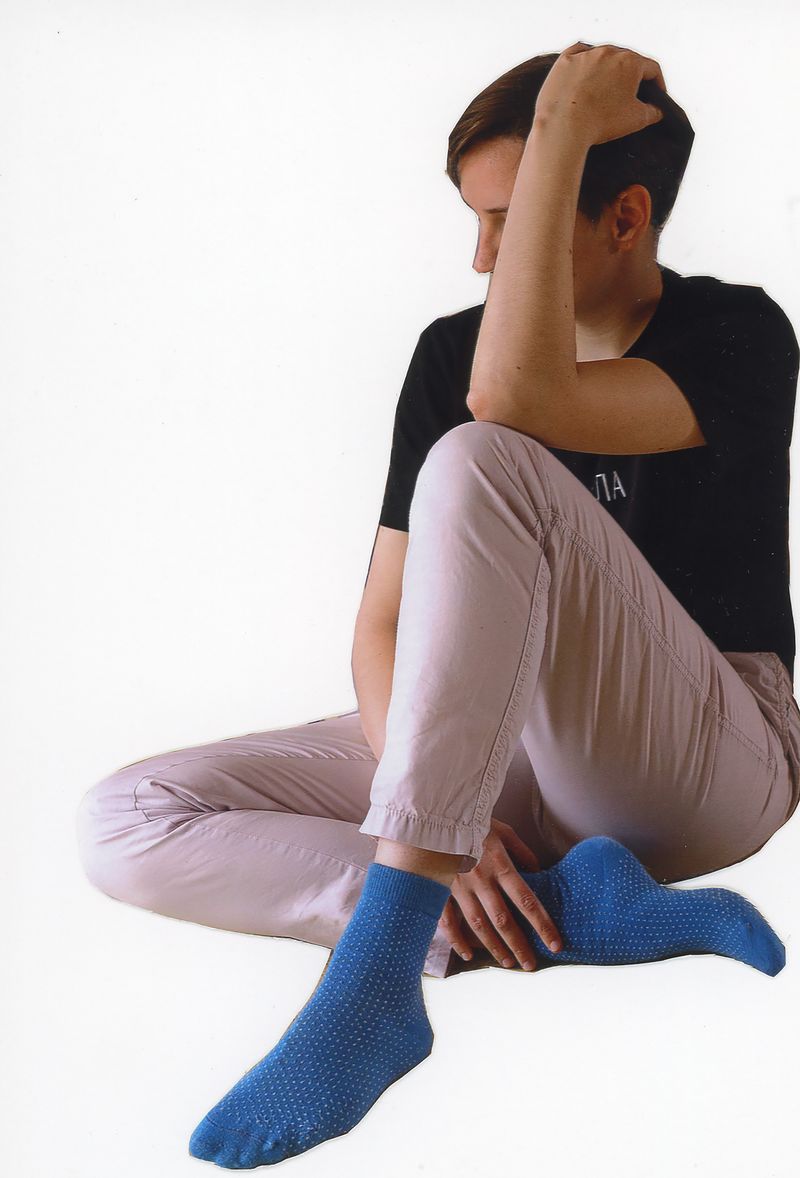

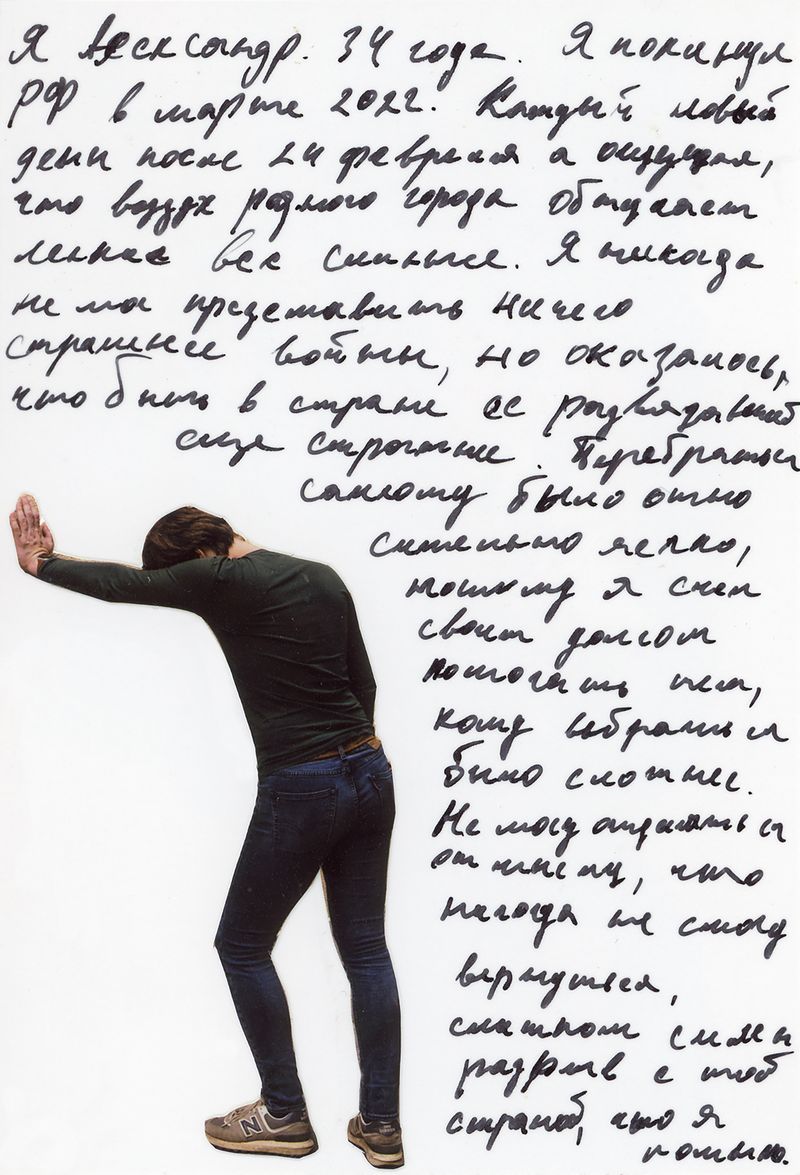

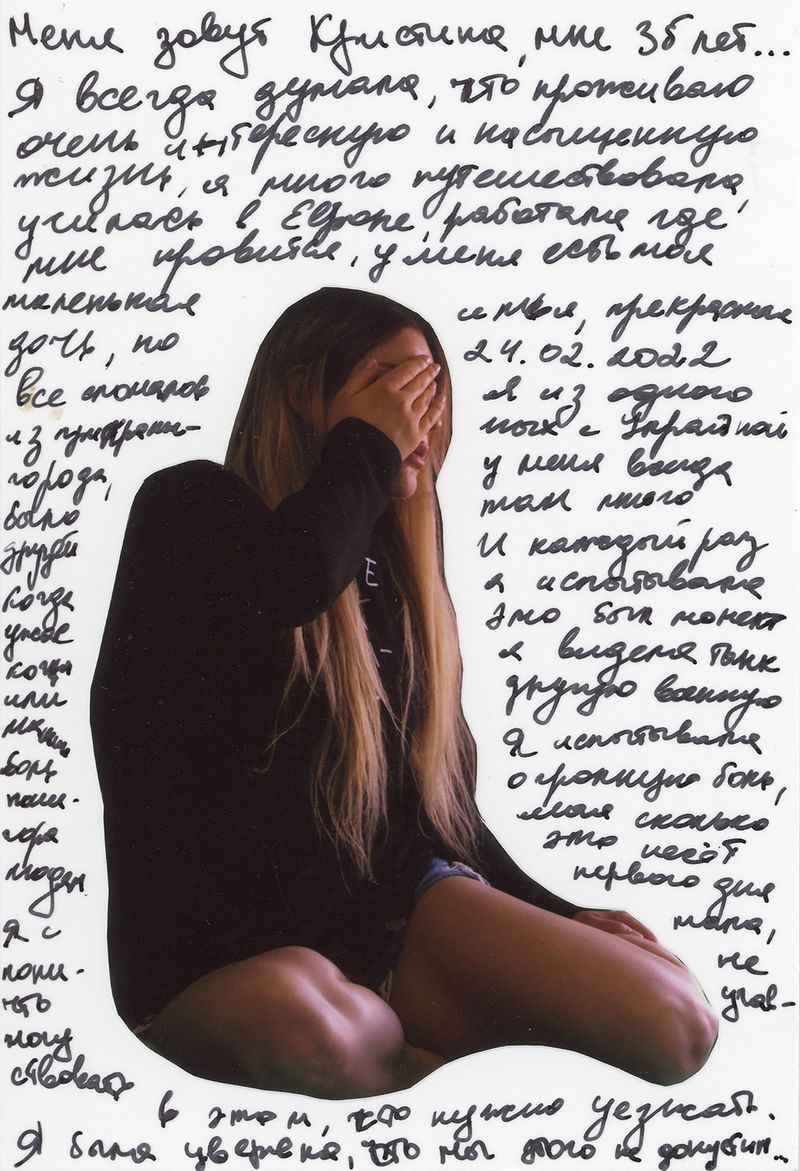

Between April and September 2023, I traveled through Italy, Germany, Serbia, Georgia, and Armenia to meet with young Russian activists and dissidents who, after the invasion of Ukraine, decided to leave their country to preserve their freedom and safety.

On February 24th, 2022, troops of the Russian Federation invaded Ukrainian territory, starting what would later be called by Putin and all his supporters a "special operation."

The war waged by the Russian president, which sowed and continues to sow death and destruction in Ukraine, has not only caused serious international imbalances, but also a drastic and irrevocable change in Russian civil society. Included in this change is the historic exodus of Russian citizens.

While there is no hard data, it is estimated that more than one million Russians have left the country without going back, so much so that the Russian Ministry of Communications itself has complained of a 10 percent shortage of IT workers.

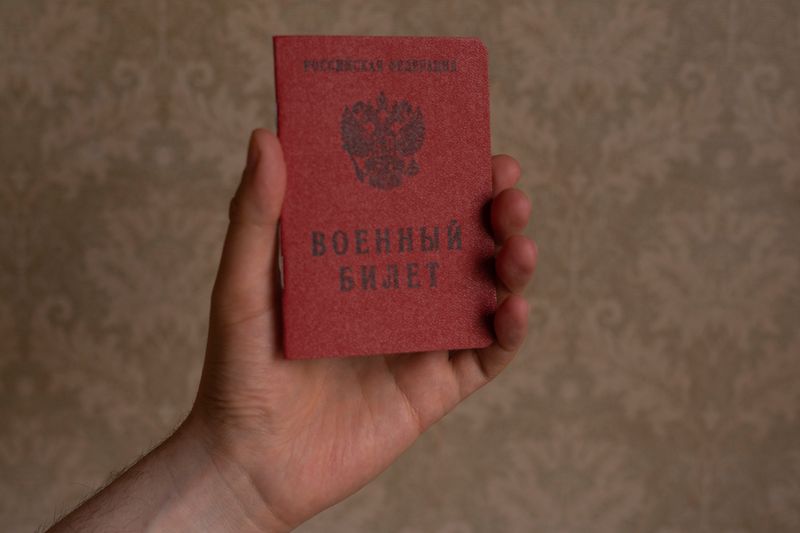

In addition to the ideological reasons related to the invasion of Ukraine, what drove such a large number of people to leave their homes was the increasingly authoritarian turn of the Russian state, which left no choice to anyone who showed opposition to Russian military actions on Ukrainian territory.

According to the OVD-Info organization, 19,735 people were arrested in Russia from February 24th , 2022 to April 21st , 2023, thanks in part to the use of facial recognition cameras installed in subways.

The count of arrests includes people stopped as a result of participating in protests or publicly broadcasting dissent against the war in Ukraine, either through social media or by displaying peace symbols, blue-yellow ribbons or objects, green ribbons, stickers in support of Ukraine. Immediately, repression came through censorship. Foreign socials such as Facebook and Twitter were blocked, human rights associations and independent news outlets were put on the foreign agent list, forced to close down and move abroad along with all those journalists who did not agree to disseminate state-controlled information. State propaganda has spread to every aspect of society, through television, on the Internet, on the streets, in schools and universities.

Over the course of these months in Italy, Germany, Serbia, Georgia and Armenia, I have met young Russian dissidents who left the country after the start of the war. Those of them who are in Europe have sought political asylum.

Some of them were arrested during the protests that erupted in the first days after the invasion of Ukraine. Others managed to escape military conscription.

They include activists and people from the LGBTQ+ community who, following the tightening of the law against homosexual propaganda, were no longer safe in their own country. I decided to have them tell their stories by their own hand, writing them on the photos. Some of them preferred not to do so because of the difficulty of summarizing in a few lines the complexity of their thoughts about this tragic page of world history and their own condition.