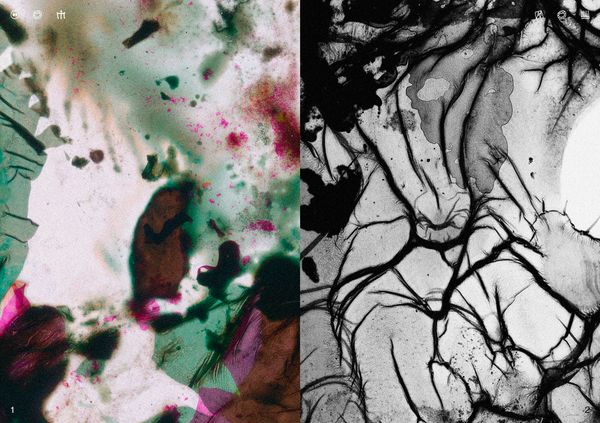

Specimen 1-101

-

Dates2024 - Ongoing

-

Author

- Topics Awards, Contemporary Issues, Documentary, Fine Art, Nature & Environment, Photobooks

- Locations Dresden, Berlin, Hamburg

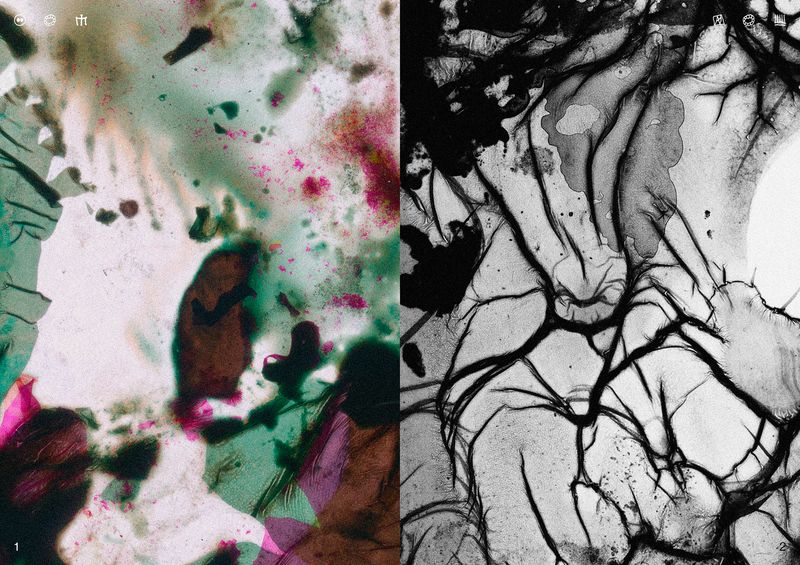

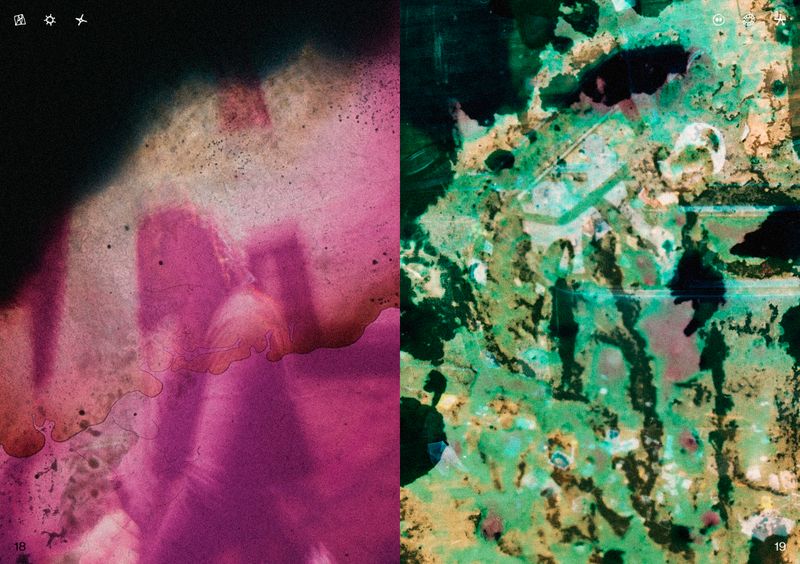

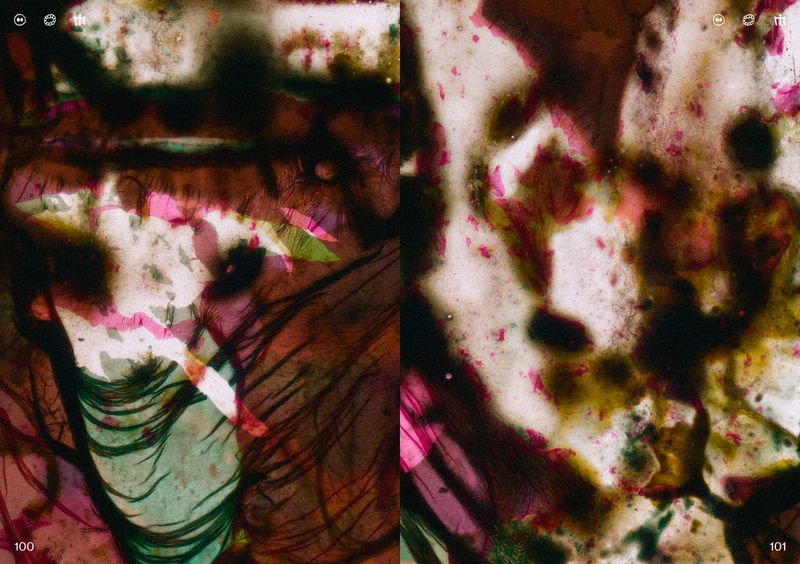

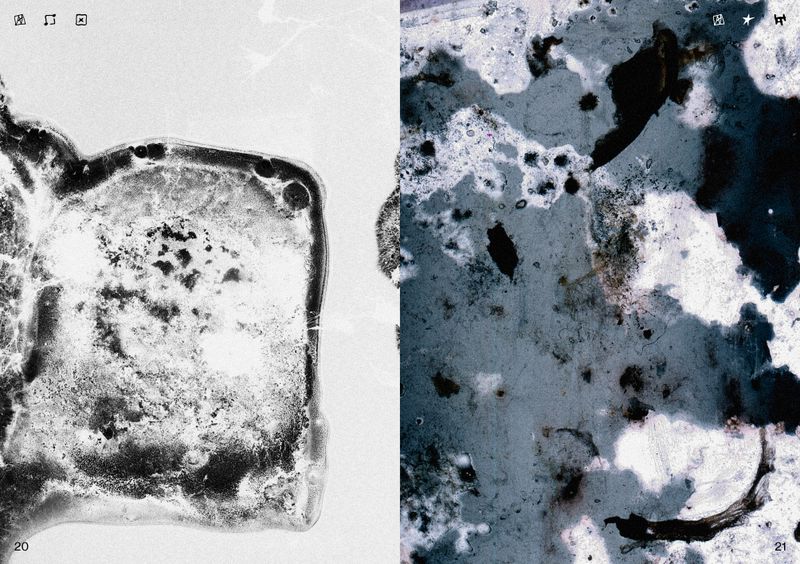

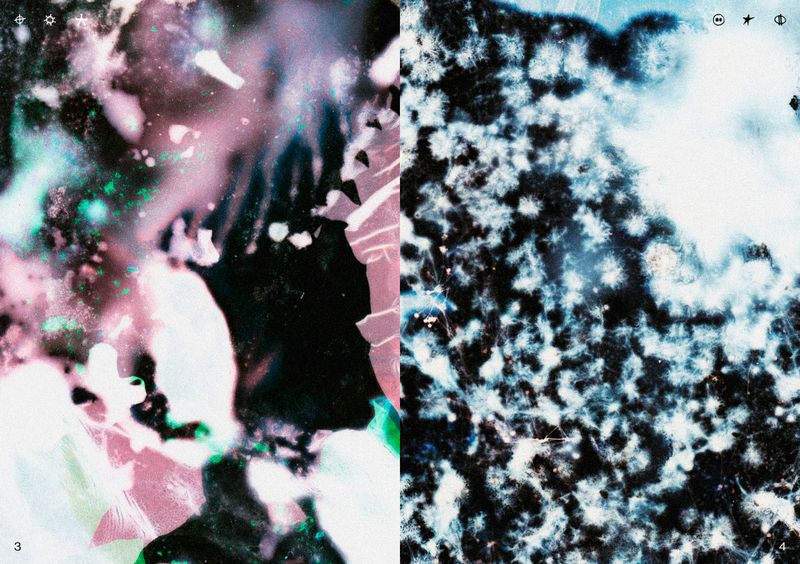

This photobook contains decayed/molded analog image carriers, the borderline of materiality and image is dissolved . It explores decay, transformation, and the physical reality of the medium, between light, chemistry, decomposition & emerging of new life.

Material Becoming : Becoming Material (Specimen 1-101)

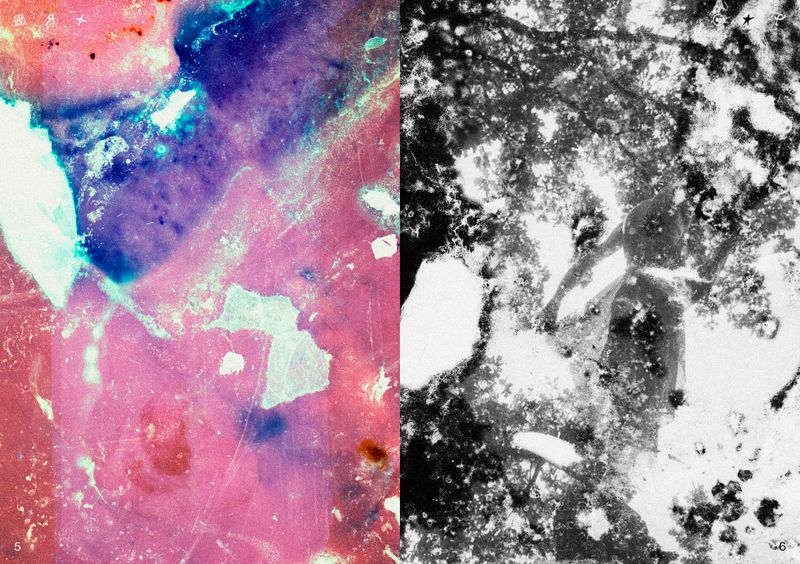

The images presented in this book are starkly different from conventional photographs. While photography has long pursued the goal of capturing and representing reality, no image can ever fully embody the reality it portrays. This quest for realism produces a paradoxical distance: the closer an image gets to the moment, the more its materiality recedes into the background. The demand for maximum realism becomes paramount, while the traces of the image’s becoming are concealed beneath a dome of supposed irrelevance. Retouching and digital editing attempt to erase the last signs of the image as a medium. The Symbols on the top corners of each Page are tied to an Atlas legend, which unbosoms the heritage of the change the Material witnessed. Germs and Organic Material were consciously bred in petri-dishes before the analogue material (negatives, slides, handprints) were exposed to them.

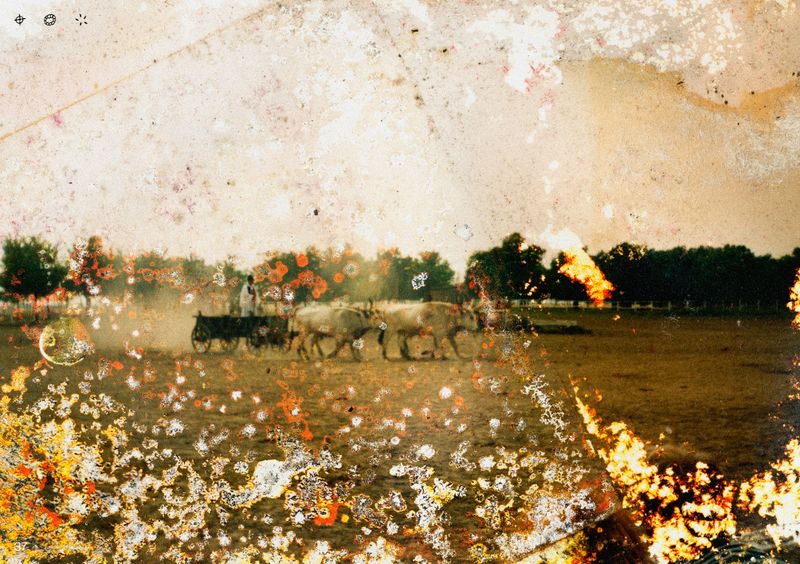

Reality and fiction blur as modern tools allow for highly realistic representations—whether through hyperrealistic photography or computer-generated imagery. In contrast, analog photography has turned away from this aim. Precisely through its artifacts and slight deviations from objective realism, it offers an alternative form of expression. It merges the captured moment with the physical trace of the material that holds it. The side effects of analog photography tell their own story: the story of the material and its life.

How far should the materiality of film enter the image? What distortions of reality occur when the medium of depiction injects a piece of itself into the picture?

Analog photography is inseparably tied to the physical world. It works with substances that were once part of nature—like the ink forming these letters (or the screen displaying them), or the toast you once ate. A gelatin-coated emulsion of silver halide crystals reacts to light: an electron migrates, a silver cation receives it, and chemical processes produce visible marks—the image. Light becomes matter. The moment becomes tangible.

Motifs only depict reality to the extent that the material allows it—the material that captures the light reflected by objects. This is the life of the analog image.

Physical processes reveal one material by transforming it into another, giving it form. Light becomes image, toast becomes body, sand becomes screen.

This process is not limited to traditional film development. When film comes into contact with other materials, the image changes—it grows more abstract, moves away from realism, and opens a space for new forms of expression.

In this body of works, the material itself becomes image. Captured reality enters into a dialogue with the life of the material after exposure—a phase that often remains hidden.

This connection between objects and their physical foundation is fascinating. Yet in our digitalized world, it is lost. The material information of film is transformed into pixel graphics. Digitization severs the image from its physical origin. Nevertheless, we can still make these processes visible—before the material loses its tangible nature. The film scanner, originally built to create digital images of the analogue Captured reality, becomes a microscope—revealing worlds of patterns, shapes, and stories that emerge from the film’s interaction with other materials and Organisms.

This interaction generates new facts, a new objecthood. Not only the reality captured by light, but also the reality born in the material itself, converge—creating compositions, dialogues, and moments that result from the incarnation of multiple components into a new form.

What was once painstakingly removed from the image now steps forward and becomes the image itself. Materiality, once sacrificed entirely to the representation of the captured moment, now takes center stage—revealing its life, its character, its properties.

These processes tell stories that go beyond the motif. They reveal the journey of the material. The introspection once found within the depicted subject is now embodied by the material itself, which becomes the protagonist. The sacredness of the materials used becomes the sacredness of the image.

These works offer abstract windows into worlds born from natural processes—worlds more closely related to our physical existence than digitally generated images.

The tools once invented to capture reality, now liberated from their subordination to the image, reveal their potential. The film interacts with other materials and becomes fertile ground for new life.

Mold becomes a companion. A decomposer, a natural agent of decay, mold returns matter to the cycle of life. Its traces remind us of the material’s mortality and its duty to return to the earth.

The dissolution of material form and its reintegration into nature is death—an inevitable end that clashes with the longing for eternal, immortal matter. In classical memento mori or still life images, death was depicted—but always through the objects shown, not through the material that shaped them.

This fragility—the physical bond with nature—is central. The film that once captured light now serves as soil for new life. In this interaction of light, chemistry, and organic growth, images emerge that go far beyond representation.

The inert, industrially processed material serves life again, the image-holding gelatine is transforming into a nurturing ground for mold. This everyday antagonist, often seen as a parasite devouring our objects, becomes the protagonist. It opens the door to visible deformation and material history. Mold leaves scars that reveal the image’s past and its material body—between the moment light was captured and the image was scanned.

It exposes the vulnerability of the material and its intertwinement with the physical world. It reveals the fragility of the image and the fact that it is subject to natural decay.

In analog image-making, physical material becomes an actor—giving tangible form to an immaterial value.

Together with light, captured reality, emotions, sentiments, life, thoughts, and other human traces enter the film’s surface. The material outcome of a physical transformation is thus emotionally charged. By adding materials that also carry signs of humanity, this emotional charge becomes more direct and tangible. Both imprint themselves onto the resulting image.

The emotional value of the represented reality is so intimate and personal that it cannot be expressed in economic terms. Feelings, life, death—this is not about monetary value but about the individual and spiritual meaning embedded in the image. The photograph becomes a bridge pointing toward individualized spirituality.

How can we recognize the significance, relevance, and emotional charge of the depicted? Does it lie in the motif’s emotional weight? In the silver embedded in the film? How does our perception shift when tears or water from a cemetery are part of the process? Do these materials carry equal emotional weight to the image’s content? What role is played by the material value of silver—or by the urine or saliva used in its de/formation?

What relationship can we enter into with the image when familiar views are overlaid with abstract distortions of a material nature? What feelings and memories does it evoke? What connections can we form between the image and our surroundings—our natural world and reality?

The answers lie solely in the eye of the beholder.