Sisyphus' Waste

-

Dates2024 - 2024

-

Author

- Topics Contemporary Issues, Documentary, Nature & Environment

- Location Nepal, Nepal

Cameras made from mountain waste reflect our impact on the environment, observing future archaeologies we will leave behind.

After four days of trekking, my brother and I made it to the base camp of Mardi Himal. It was the first time since we were children that we had hung out as ‘friends’. Each of us had grown into such different people, despite having come from the same place. How had we ended up so far apart?

There had been a couple of small arguments on the ascent, more bickering than anything else, though they were punctuated by reflective conversations, grounded in growth and a more mature look back on our youth and who we had become. This shifted sharply on the final morning of our trek. In order to get as much time as possible at the base camp, surrounded by the 8000m peaks, you had to leave the high camp well before sunrise. Ever a night owl, this wasn’t exactly conducive with my established rhythm. He woke me early, and suddenly it was like he had become our father. In his mannerisms and tone, it was as though he was channeling how he had seen him treat me all those years ago. I hated him for it. That morning, I very nearly didn’t make it to the base camp with him.

Pushing through, after a fair amount of pre-coffee early morning effort, we made it. There weren’t nearly as many of us at this point as had started early in the morning. Many people turned back at the final viewpoint, perceiving it as not worth the extra effort for such an incremental increase in nature’s wonder. But in that, the relative solitude where others had not continued added something else entirely: a sense of magic and awe that heightened the spectacle around us.

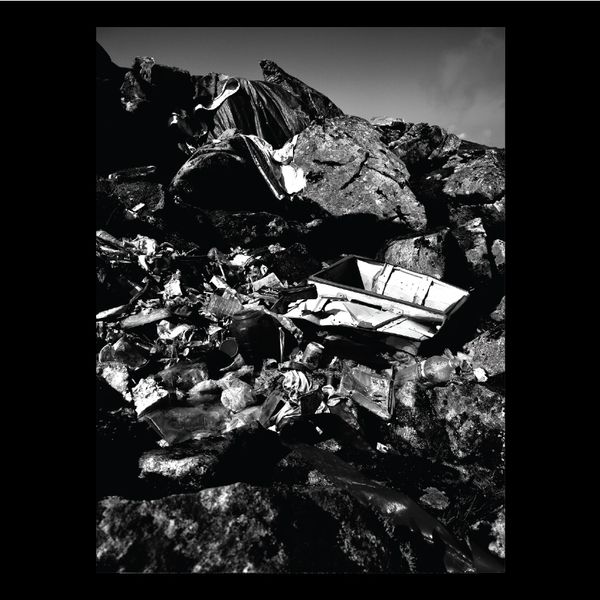

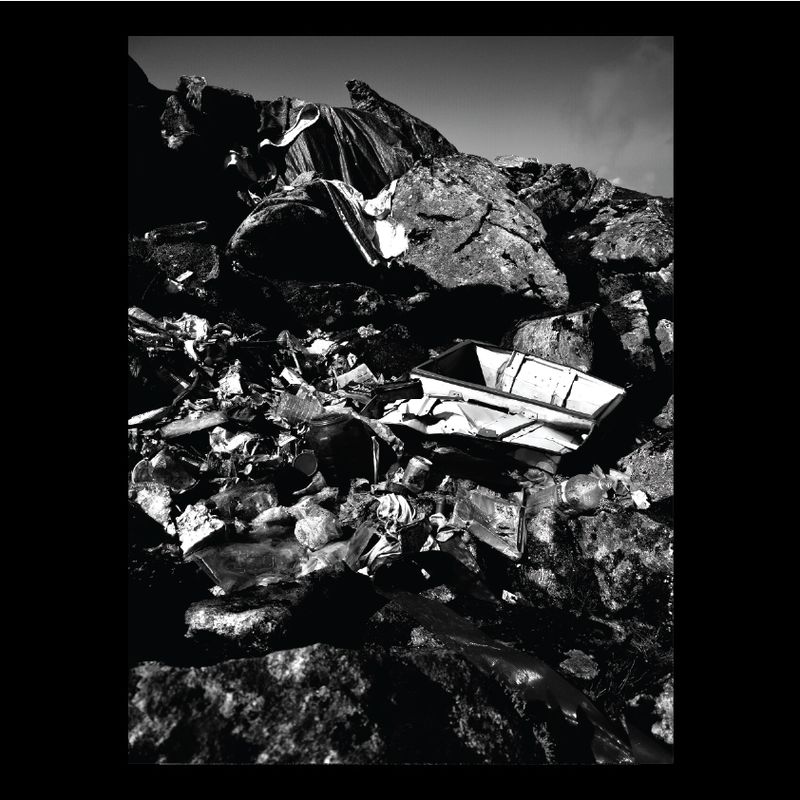

Everyone was taking in the majesty of the mountain range, breathing the clean but thin air, when I suddenly noticed it. A waste dump. There, at 4500m, where we humans had trekked for a minimum of two days to reach (we took it very slowly). An environment inhospitable, where after a certain altitude you should not even leave an apple core because it does not belong to the biome you are entering, and yet here was a waste dump. Trekkers had seen fit to abandon the contents of their bags: the wrappers and cladding of their commercially made and packed fuel, consumed then discarded. How do we think it’s acceptable to act with such entitlement toward our environment?

Once, this place was unmoved for millennia, except by tectonic forces below. Scarred only by time, weather, and the passing of seasons clinging to the slopes in shifting cycles. Temporality made plain through the change of colour and form.

Humans changed that. With our presence on the slopes, we began shaping them into an ergonomic playground for our desires, carving steps and building huts: making accessible those places once seen only by the wild.

With this came the waste. Remnants of our presence. Marks of our fall. Remaining on the mountains as though a part of her form.

Compelled to respond, on the descent I collected 2.5kg of metal waste, which I affixed to the outside of my large trekking bag. I clinked and clanged like a mountain goat. This white noise almost calmed my tinnitus, serving too as a constant reminder of the truth of our presence, hidden in plain sight. My brother, somewhat politely, asked me to find another way of attaching the metal after the second day. It was driving him mad and ruining his peace in the space. I acquiesced with a sense of regret. Later, when I asked to see his photos from the mountain, I noticed that in all of them he had framed out the waste that was ever-present. Funny how we make these things and yet refuse to record them for how they truly are.

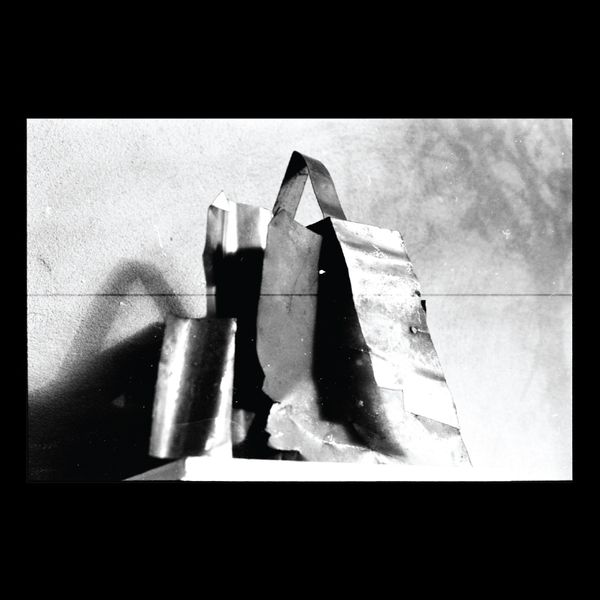

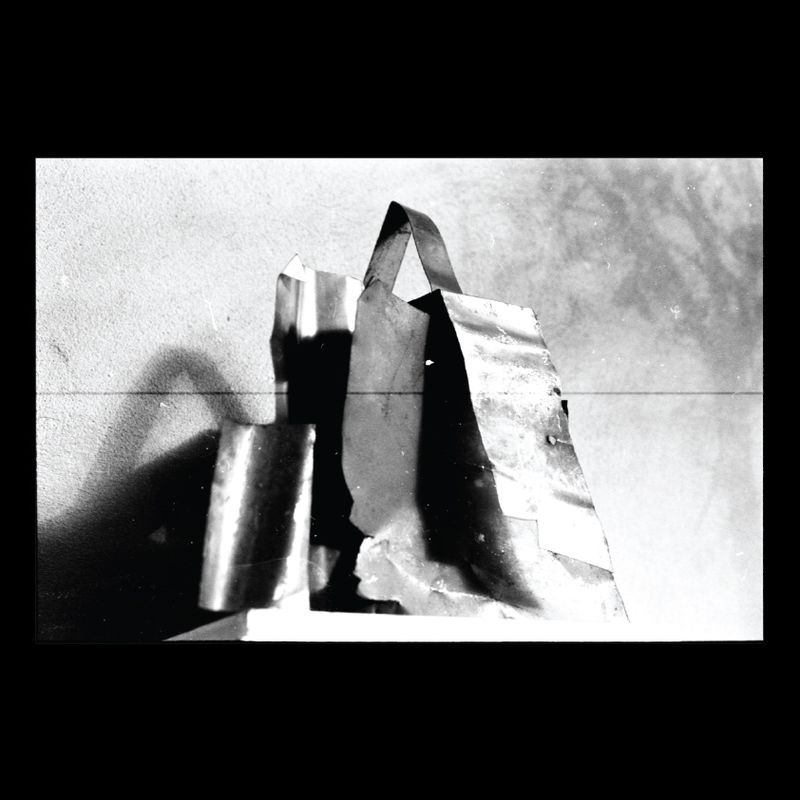

Back in Pokhara, after a week or so of back and forth, miscommunications mostly due to my lack of Nepalese, I had two cameras fabricated with the help of a local metalworker, using the mountain waste.

I then went back up the mountain. Twice. Documenting the waste on the slopes with the camera made from that very waste, looking at the marks we had left through the very marks we had left.

One thing I had not accounted for during my test exposures in Pokhara was how the heightened light intensity and UV levels, due to the thinner ozone, might affect the final images. The negatives came out overexposed. Often, the only recognisable mark was that of my own fingerprint, left behind as I sweatily and stressfully changed film in a dark bag at 4500m. Initially disappointed, after all the time and effort to get this far, I later realised during quiet reflection in the dark that it served instead as a metaphor: the mountain's overexposure to humans, left printed as a fingerprint on her surface.

By bringing elements of this waste down from altitude and turning it into a camera, then taking the re-contextualised material (for that is all waste really is, material that has lost its assigned purpose) back up to height, I aim to share in a view not just of the mountains, but of what we’ve done to them. A vision of the ‘permanent’, now changed. Sharing in sight with the mountain itself, so we might begin to see through its eyes, a glimpse into the truth we so often avoid when documenting our time there. Not the sublime or the untouched, but the mark we leave behind.

There is something Sisyphean in it all, hauling what was cast off back up the slopes, trying to make meaning from what was discarded, as though repetition might reveal a truth we keep refusing to learn.

Another strange revelation from the project was the presence of moths crushed all along the steps we had carved for ourselves. I became quite obsessed with these quietly beautiful, white and black striped winged beasts that seemed so intentionally littered along the path. Documenting them, I made a small portfolio of their broken forms.

Then, at a tea house on that first ascent with my brother, I found a huge pile all brushed together. Some of them were still fluttering in a strange, disembodied way. I jumped to it and began photographing the sad-looking mass, before a local ran out and pushed me away. He pointed at the moths, then at his eyes. Confused, I stopped, unsure if I had somehow offended him.

It was only later, further up the mountain, that another tea house owner explained: the moths make you go blind.

I didn’t believe him at first. I thought he was joking. But after some research I discovered that it was a well-documented phenomenon, known as SHAPU (Seasonal Hyper Acute Pan-Uveitis) an under-researched condition first recorded in the Himalayas in the 1970s. When the moths land in your eyes, they leave behind tiny hairs carried on their backs, which in turn carry some kind of histamine our bodies react to. A week later, without warning, it can cause irreversible blindness in the affected eye or eyes.

Almost as though, in response to us ruining the site of nature, she has decided to take our sight in return…