People Of Clay

-

Dates2016 - 2023

-

Author

- Location Assam, India

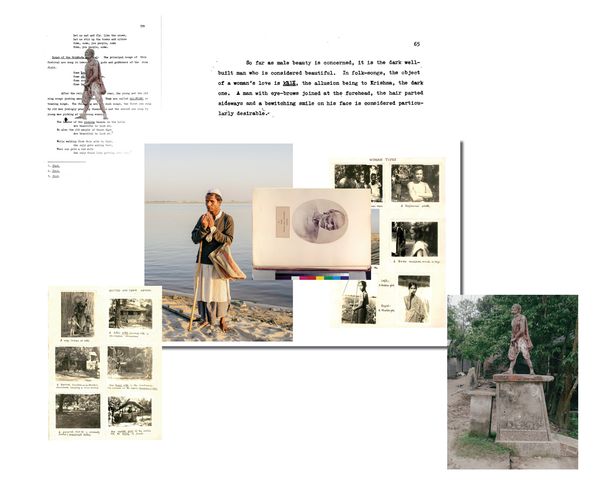

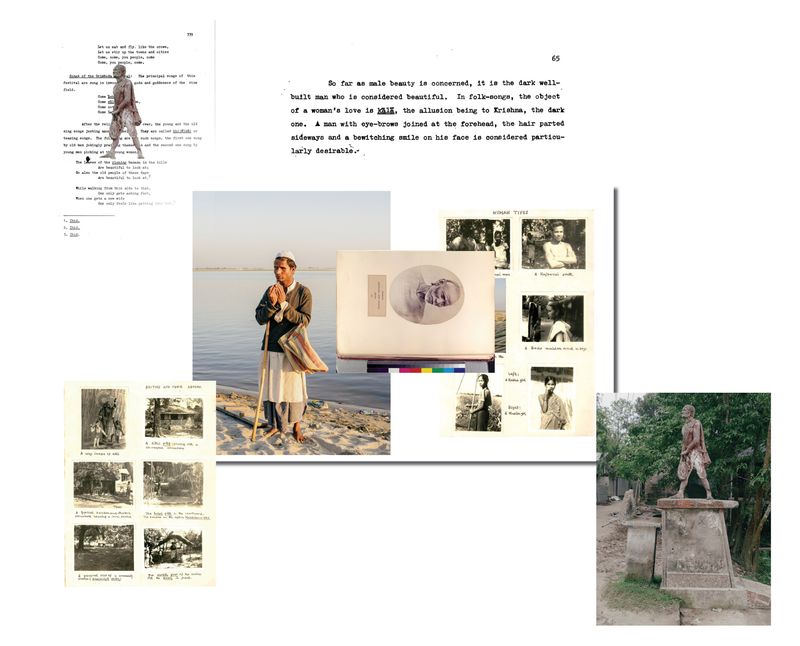

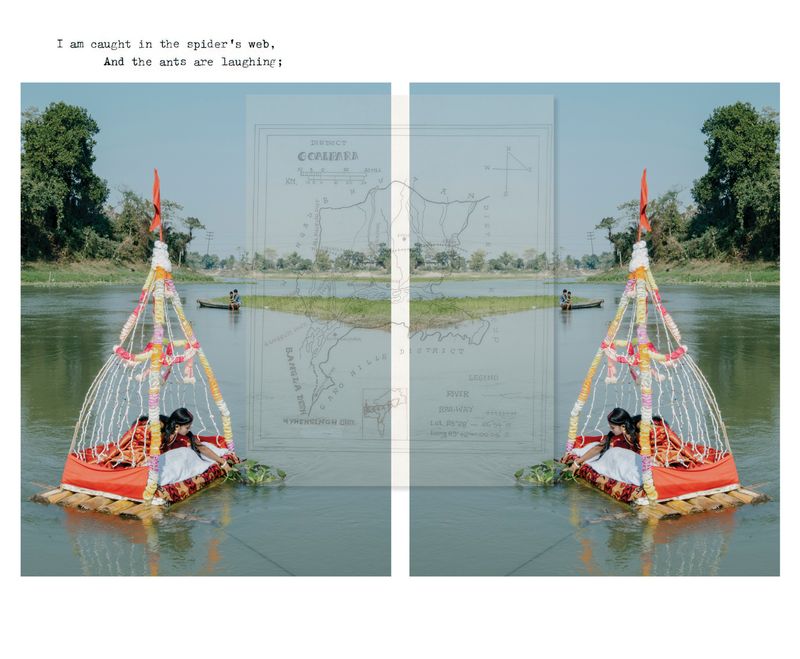

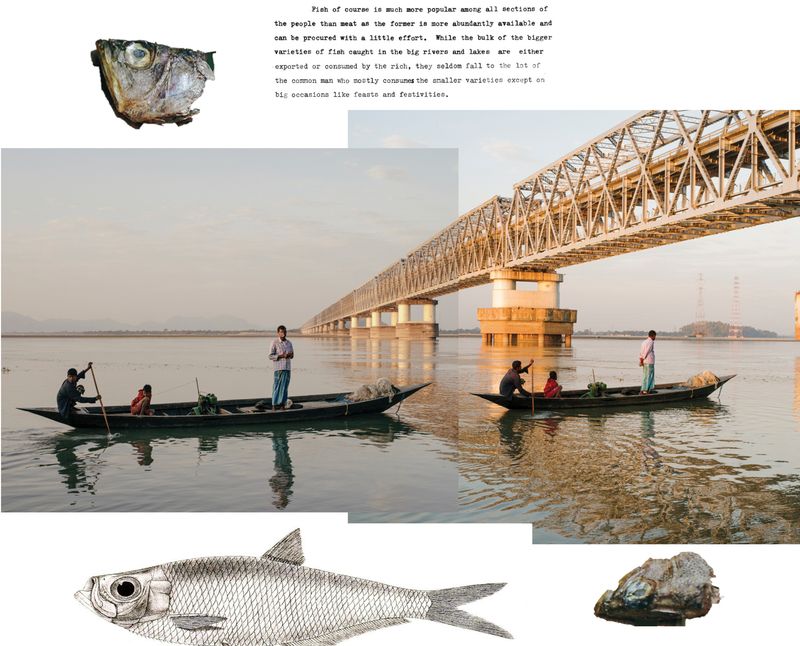

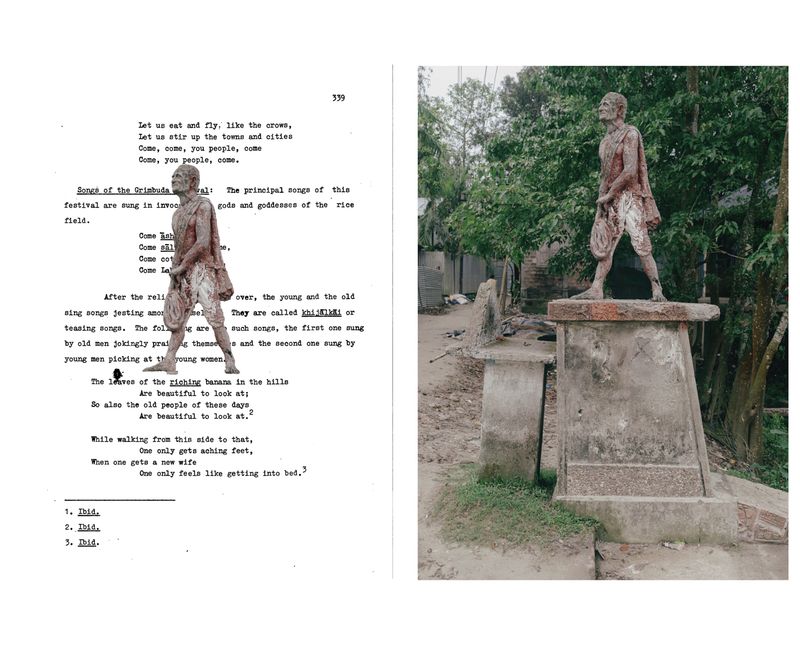

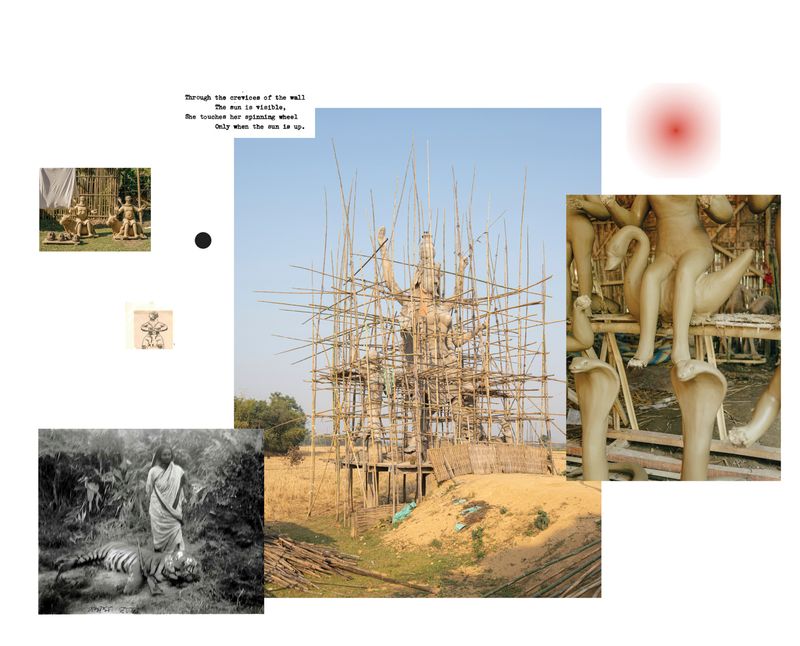

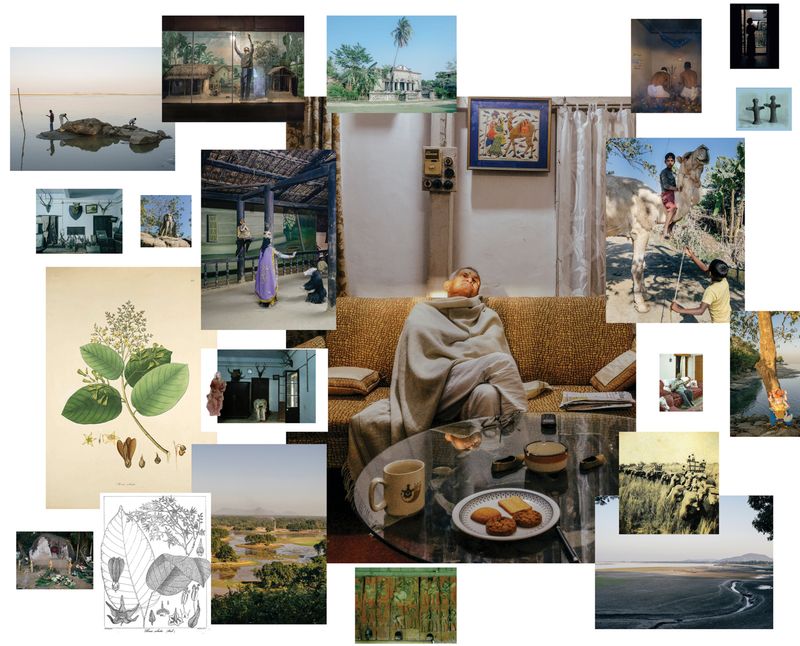

People of Clay is interested in songs that tell stories. Using a blend of text, archival materials, and photography, the work unravels the impact of colonial classification and the songs that bring back from cultural oblivion.

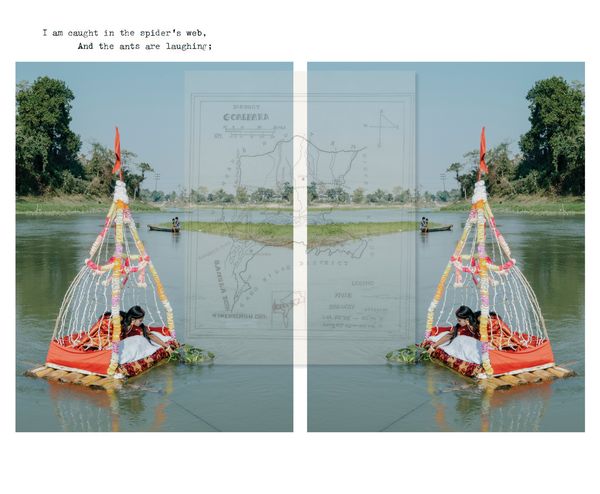

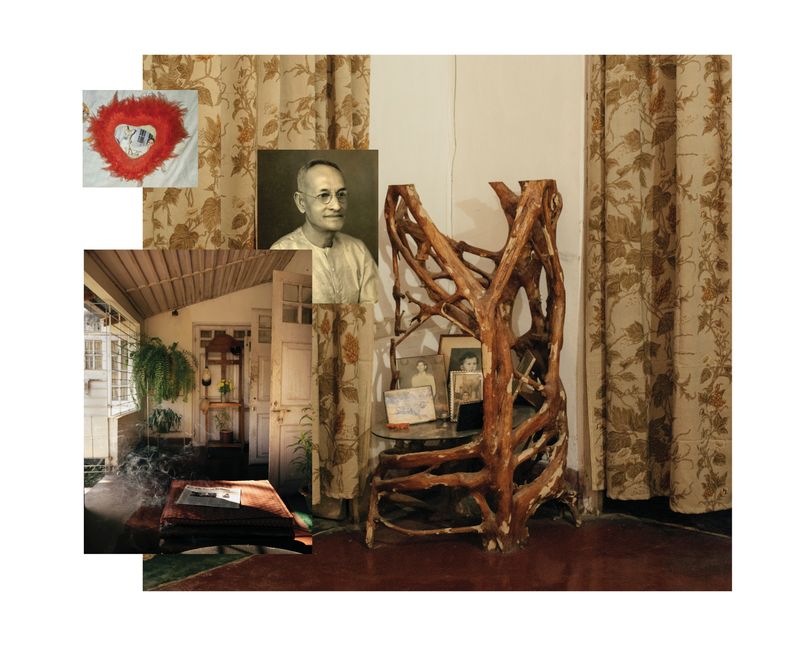

It took me many years to notice that, at quieter moments when no one was listening, she would sing. Simple tunes with haunting notes of melancholy. I tried to grasp the words of a language I was yet to ascertain: folksongs of a forgotten people.

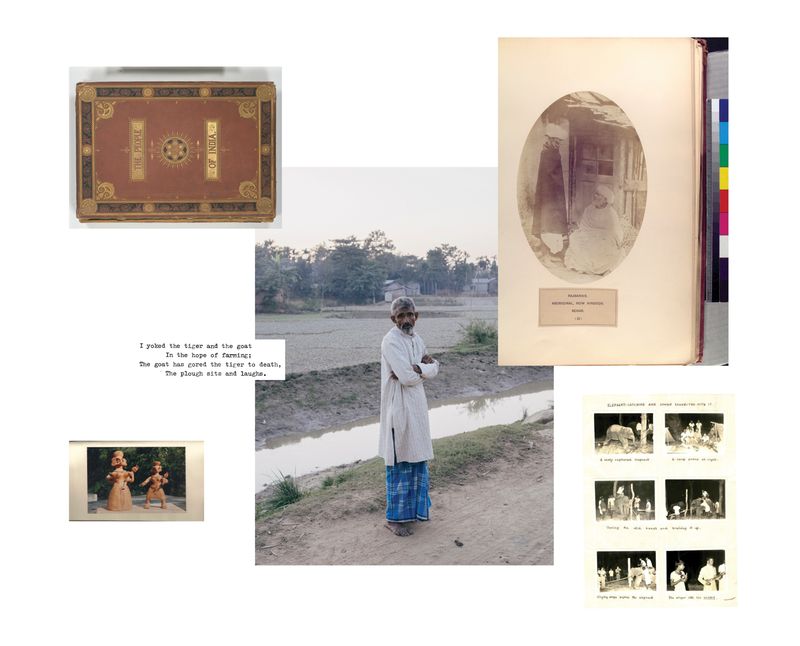

Using these local songs as a map, I attempted to sculpt a new, amorphous personal identity, not inherited from birth but through love. I travelled to her corner of India, inherited by marriage—a region bordering Bangladesh, bifurcated between the constructed colonial borders of Assam and Bengal. The elision of their identity is apparent in colonial documents. The title for an image of an elderly Rajbanshi man in “The People of India,” a nineteenth-century British ethnographic album compiled in the wake of the 1857 revolution, reads “Rajbansi. Aboriginal. Now Hindoos.” This description is both pejorative and inaccurate since the Rajbanshis were not entirely Hindu. Their folk culture, language, and traditions were relegated to obscurity, subsumed by a larger regional identity. The people were left clutching at the remains of their folk culture within these boundaries, while slowly drifting into amnesia.

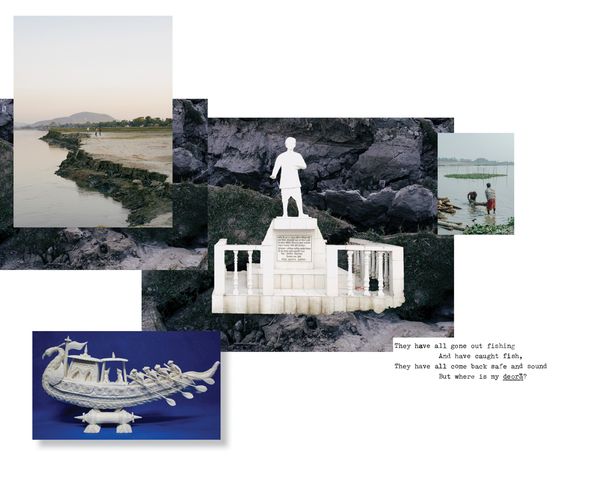

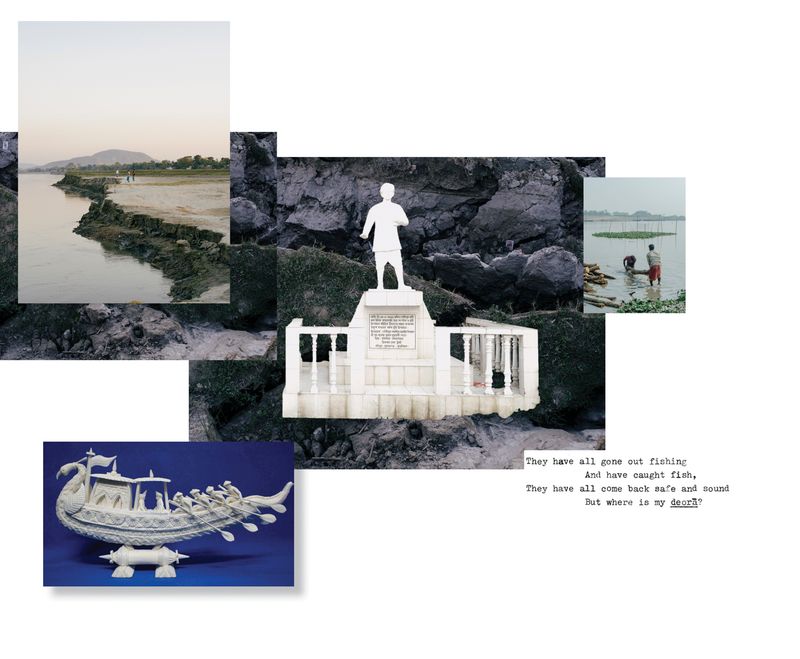

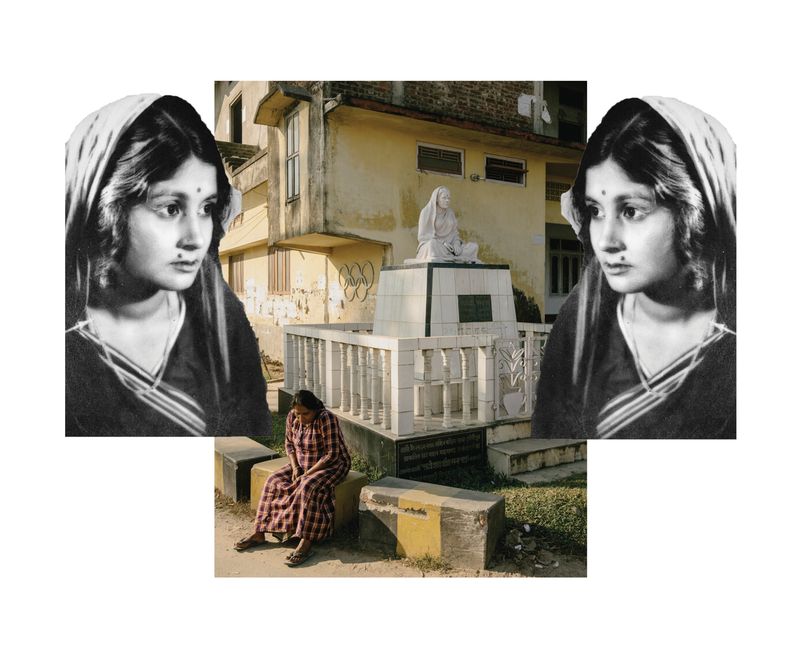

Enter Pratima Barua Pandey, who abandoned her education to take up collecting and singing the songs of her people. From the brink of being forgotten, she brought back the lores, myths, and legends through song. At this time, like a folktale unravelling, “People of Clay” attempts to understand and pick at the remnants of this folk psychogeography, of how simple songs can be carriers of pre-colonial identity. The work is presented as an assemblage of text, archival material, photographs, and lyrics.

Interweaving personal narratives with a broader socio-political canvas, the pictures invite reflection on the fluidity of identity against the rigidities of colonial legacies. A narrative enriched by love and community engagement, it challenges the permanence of imposed identities, suggesting a more dynamic, interconnected conception of cultural lineage.