OIL SANDS / Tar Sands

-

Dates2010 - Ongoing

-

Author

- Topics Contemporary Issues, Editorial

- Location Fort McMurray, Canada

Oil Sands – Curse or Blessing? // Alan GignouxNorthern Alberta is home to some of the world’s largest natural bitumen deposits. The determination of oil companies to access that resource has had a number of consequences: chief among them are colossal economic growth and major environmental

Environmentalists have called the exploitation of the oil sands in Northern Alberta “one of the biggest global warming crimes in history.” Writer Jeff Rubin states that “the production of a single barrel of oil pollutes 250 gallons (946 litres) of freshwater and emits over 220 pounds (100 kilos) of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere.” According to Natural Resources Canada, in 2018 Alberta produced 2.9 million barrels per day, making the industry’s contribution to global warming one of the most significant in the world.

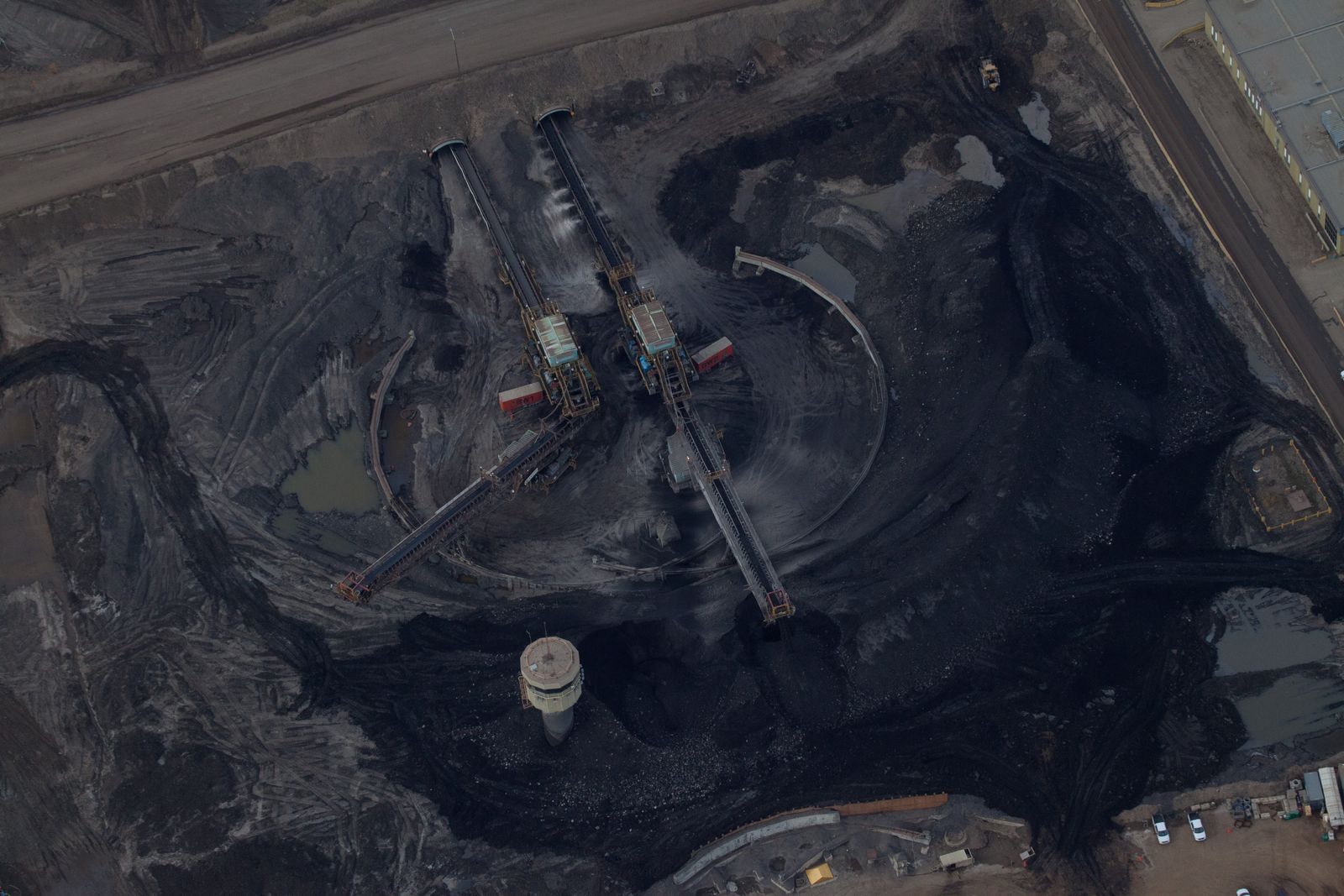

The main oil sands development at Fort McMurray is so large it is visible from space. In order to access the oil deposits, vast stretches of boreal forest have been destroyed and irreplaceable wetlands with the wildlife, flora and fauna they support, lost forever. In their place are vast surface mining pits where earth moving equipment and mammoth bucket wheels cut away at the “overburden” of surface growth to access the black earth and bituminous oils sands beneath. The bitumen is then separated from the unwanted substances in the oil sands mixture yielding by-products, such as sulphur, which is stored in massive yellow piles, and a toxic slurry of heavy metals and hydrocarbons, captured in extensive tailings ponds.

The industry is accused of water and air pollution. Residents complain of health problems among both human and animal populations. Farmer Alain Labreque felt forced to abandon his property in Peace River because of air pollution from a neighbouring in situ mining operation: “Our permanent house has become an unliveable environment,” he comments. Woodland Cree First Nation member and Cadotte Lake resident Donna Ominayak says: “Nowadays, if you don’t work for the oil companies you don’t amount to anything, because that’s all there is – they’ve overwhelmed us. They’ve destroyed our land, our habitat, our water - they’ve polluted our air.”

Despite this, the majority of Canadians are in agreement that the Oil Sands make a significant contribution to the provincial and national economies, providing essential employment and revenues. “We have the highest incomes in Canada, the highest disposable income, the lowest taxes of any jurisdiction,” says Frank Oberle, member of the legislative assembly for the Peace River Constituency in Alberta.

However, this affluence comes at a price, not only for the environment, but also the people who work in the oil industry. In the words of Dr John O’Connor, a medical doctor in Alberta, “In a one-industry region, thousands of workers and their families become trapped by the “velvet handcuffs” of employment. With above-average wages, and outrageous real estate prices, a population of virtual hamsters trapped in wheels has become emblematic of Northern Alberta. With no remotely comparable incomes anywhere else in Canada, and frequently unimaginable debt loads, a captive, enslaved populace has little or no options.”

There is some positive news - possibly as a result of environmental activism, the oil companies are working to improve their machinery and processes to decrease their impact on the environment. Local activist and farmer Wayne Groot notes: “The plants being built now do a much better job than they did 30 or 40 years ago.”

With centuries of bitumen reserves remaining below ground in the region and demand for fossil fuels still high, it seems that – curse or blessing – the oil sands industry in Canada is likely to continue unabated for the foreseeable future.