Last Wildest Place

-

Dates2013 - Ongoing

-

Author

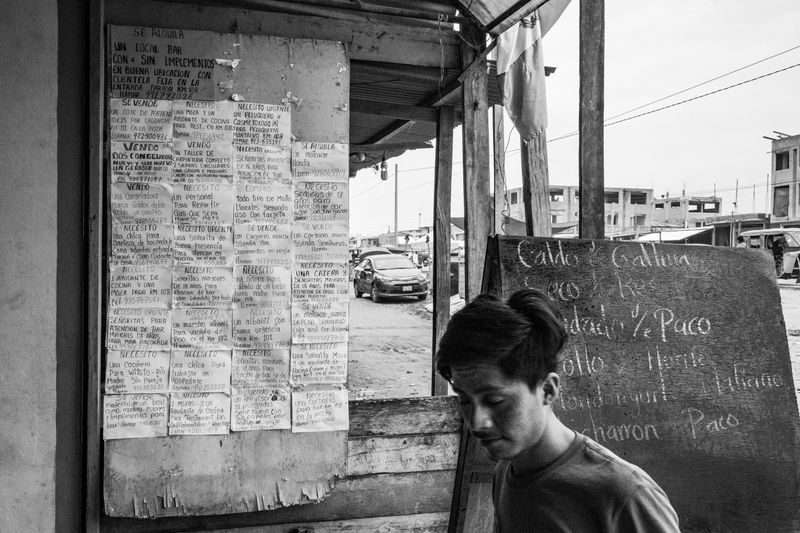

- Locations Ucayali, Peru, Purús Province, Manú Province

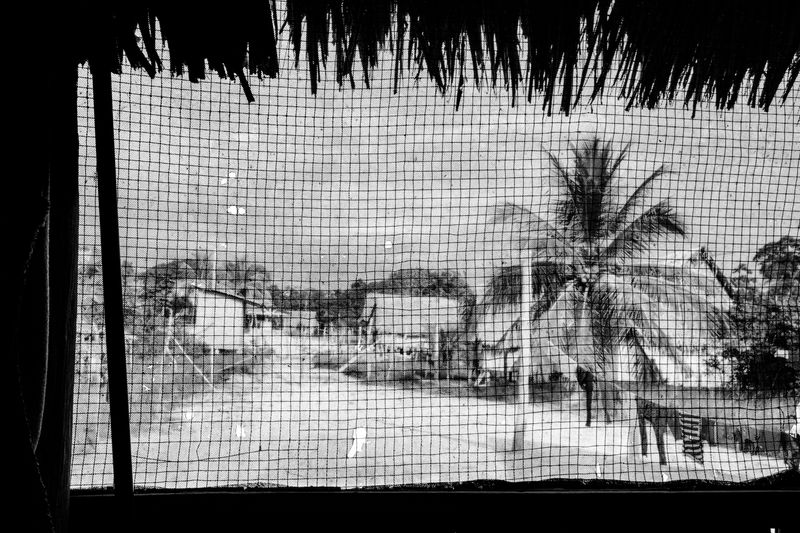

The Purús/Manu region is one of the last most isolated places in the Amazon, where threatened but still intact ecosystems provide for remote indigenous communities as well as water, oxygen, climate stability, and biological diversity for us all.

LAST WILDEST PLACE is a decade-plus-long, ongoing project based on a simple fact: The Amazon Matters. At over a billion acres, the Amazon Basin is bigger than the next two largest tropical forests combined. It alone accounts for half the planet’s remaining rainforest, 30% of all terrestrial species, 20% of our world’s freshwater, and 20% of the global oxygen. It provides climate stability for the entire planet and the carbon stored in its forests— and released by its deforestation— affects us all.

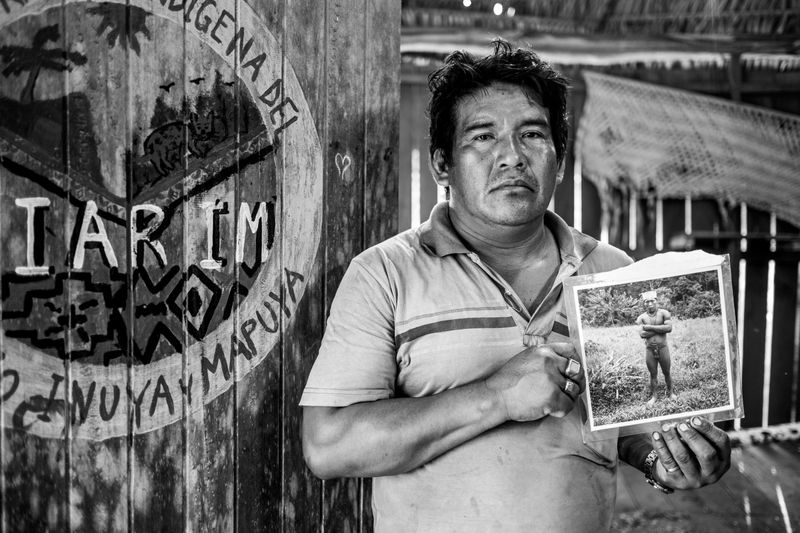

Within the Amazon, the Purús/Manu region in southeastern Peru is one of the most remote and inaccessible, where still-intact and uniquely biodiverse ecosystems provide sustenance for settled indigenous communities and is home to perhaps the highest concentration of isolated “uncontacted” tribes on Earth. While still largely undeveloped, this last wildest place is increasingly threatened by logging, illegal and unregulated gold mining (Peru is the largest gold producer in South America and in the top ten globally), coca farms and processing (for cocaine), land trafficking, oil and gas development, cattle grazing, agricultural expansion, Christian missionaries, pharmaceutical exploitation, extreme fires and drought, and the legal and illegal road construction projects that open access to previously inaccessible forests with devastating— often irrevocable— impacts on the ecosystems and all who depend on them.

I first visited the Upper Amazon in 2013 and have returned many times spending more than a year in total in the jungle. The pandemic, which limited legitimate expeditions as well as enforcement patrols, left the region especially vulnerable to increased illegal activity. As we have emerged from this restrictive dynamic and now into the reality of an increasingly uncertain and unstable socio-political global environment, the extent of new unregulated and illegal activities in this unique ecosystem makes raising awareness more critical than ever.

We have at least one trip planned in fall/winter 2025. It will be focused Alto Esperanza, an Amahuaca community in the headwaters of the Inuya River that is positioned to be the first Indigenous community in initial contact in Peru’s history to obtain title to their land. And with additional grant funds and/or support in the form of this book award, we would do at least one additional expedition in early 2026 as well, ideally in consultation with the publishers and to finalize a book edit.