Kitengela

-

Dates2019 - 2024

-

Author

- Location Kitengela, Kenya

Kitengela is a village crafted from recycled glass, embodying the vision of a utopia where art and nature intertwine. Simonet captures the vibrant yet fragmented narrative of this place, revealing its artistic ambitions and its sociocultural landscape.

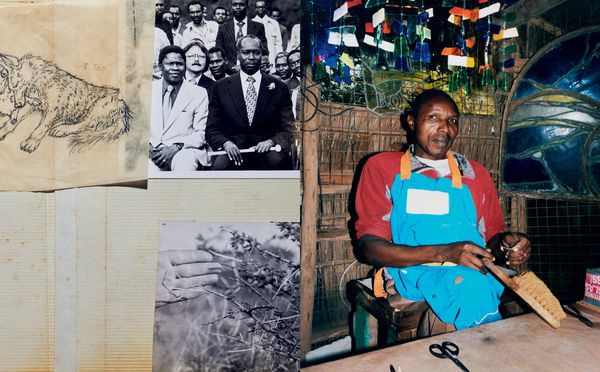

How may one begin to tell the story of Kitengela, a five-acre labyrinthian home overlooking the Kiserian River, built out of recycled glass and aluminum cans by German artist Nani Croze in the early 1980s and now ran as a glass-blowing factory, business and touristic venue by Croze’s son, Anselm? How may we look into the realities of white settlement, circulation of knowledge, division of labor, stratification of power and family feuds – retrospectively and from afar, with neither naivety nor caricature?

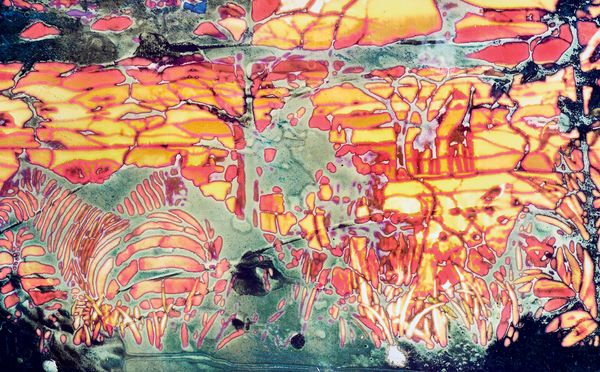

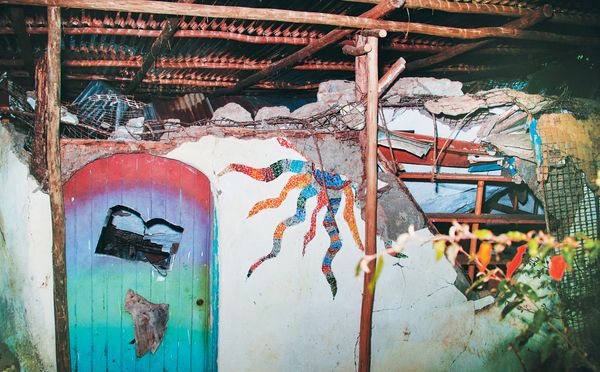

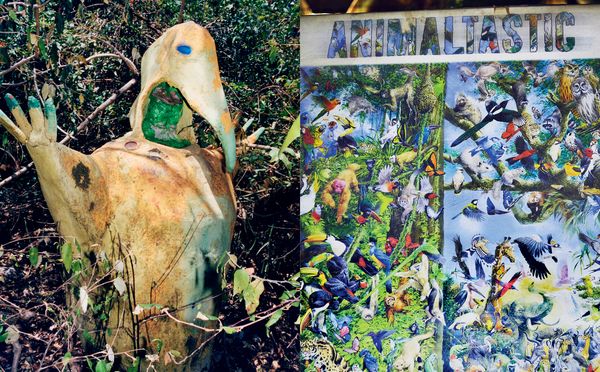

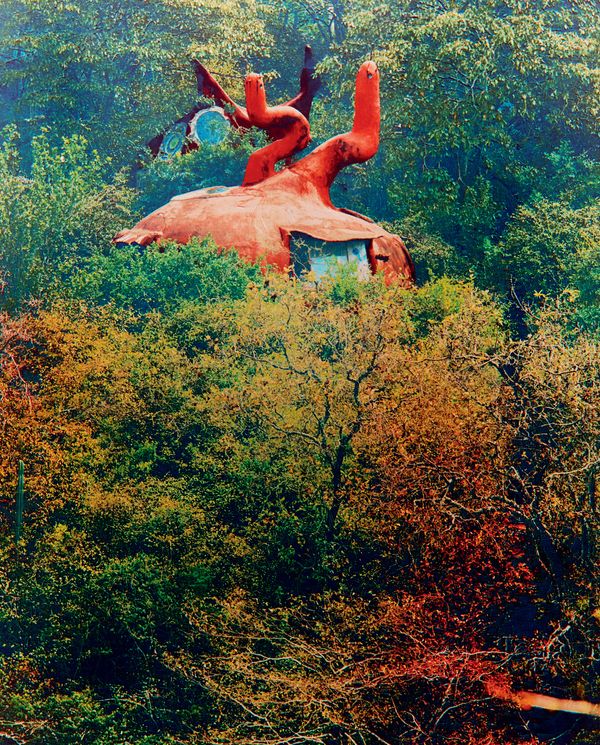

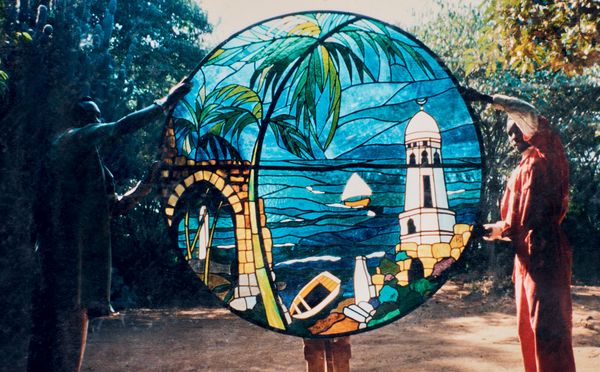

Jean-Vincent Simonet knows this story may only be told through fragments. He starts out in honest and literal fashion, meaning: we begin with the beginning, i.e at the entrance, glancing from the threshold, foreigners to this place. There’s a fairytale-like quality to the first image: the tip of a copper-colored castle pointing out of the forest, as both mirage and horizon; a pledge to intrigue. Steps are then furthered in symmetry, and symmetry comes back in hiccups throughout – as if to give a grammar to the hoarding chaos. Kitengela weaves a patchwork of paraphernalia and souvenirs. The project unfolds with a mirroring tempo: it collages interior with interior, serpentine floral shapes, front and back of an exhibition flyer, a series of shape-headed spoons following one another in portrait gallery-style. Our walkthrough goes crescendo, with a gradual surrender to the overload. We stumble upon posters, scrapbooks, a subscription to the East African Wild Life Society; Hundertwasser’s bleeding building; an alchemist’s dirtied nomenclature; a family album half-eaten by a gang of rats. Simonet digs through the mess, takes pictures of pictures, duplicates to the point where authorship dissolves into magmatic effects. He draws an equivalence between the stain-glass walls and the surface of the page. Increasingly scratched out, covered in cracks, the photographic imprint pulls towards abstraction. Images bear the marks of wear and tear; they’re blinded by light, oxidized by rain or plastic. Some have stared at the sun for a little too long.

There’s somewhat of a house-emptying feeling to Simonet’s account of Kitengela: an attempt to both record, rescue and index; to go through personal belongings and sever between the essential, the superfluous – a process similar to that of editing. It portrays Croze’s house in its social uses, as both a workplace and childhood home; a live-sized bestiary where animals mingle with their stone alter egos in the sculpture garden. It also bears witness to a prowess in lifestyle and design – one of negating ornament in its function to adorn; ornament as the “frontier of the surface” here stretching into structure, boundaries blurred between wall and window, woman and wilderness.

Simonet enters Kitengela with palpable anecdotes, material clues transformed to archive through the act of photography. The journey takes on the Poe-like quality of narratives where a protagonist is invited into an eerie household and finds themself inexplicably trapped, as if contaminated by the walls, furniture and fauna – only to realize they were never a guest, but in fact the owner of the house. Kitengela doesn’t borrow much from the Usher estate, except from the fact that it was also crumbling down. Before it did so, plans were set to make it into a destination. On www.kitengela.glass, one may now book Anselm’s “4 bedroom family cottage with giant verandah”, a “2.5 bedroom Gaudiesque build” or simply “sip cappuccino at a funky, chunky mosaic table”.

This project works as a visual inquiry into the fate of privatized utopias. It also resonates as an exercise against oblivion; but one that is stripped of any nostalgia. Memories aren’t featured in washed-out tones, or decaying colors; they’re instead made more vivid, pulsatory. If a place is always retrospective, then how shall we end? We remain stuck in iridescence.

Text by Salomé Burstein