Kintsugi

-

Dates2024 - 2025

-

Author

- Topics Daily Life

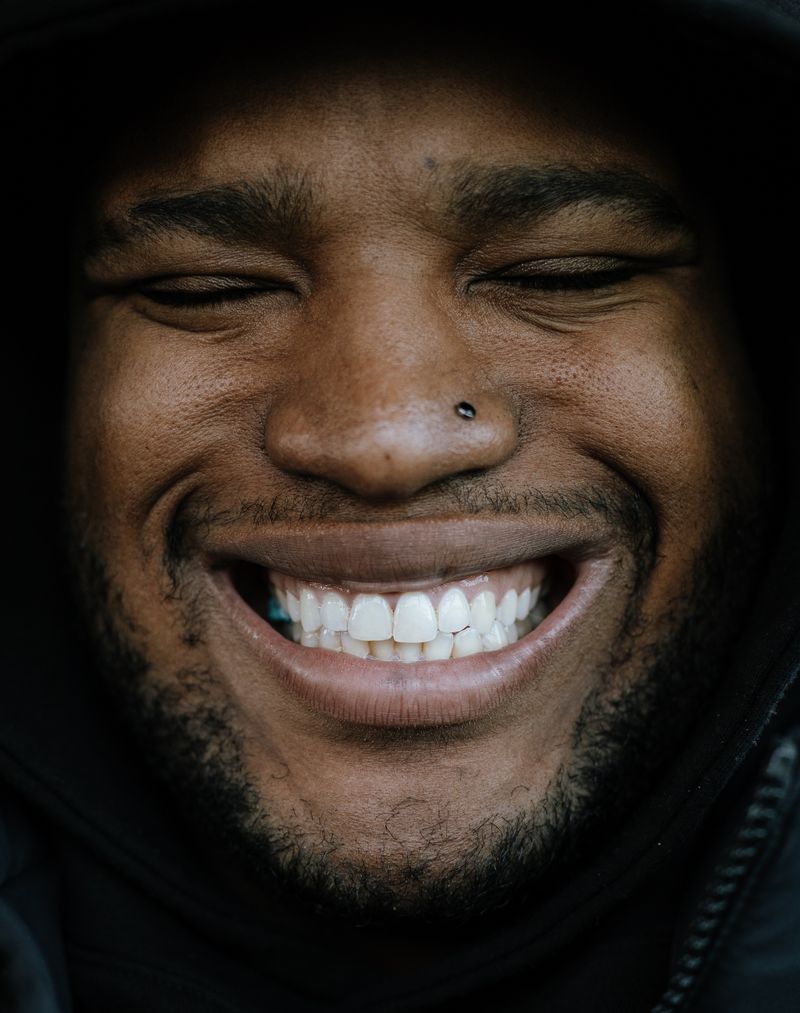

“Kintsugi”. Inspired by the Japanese art of repairing broken pottery with gold, this series is a reflection of the beauty that exists in brokenness.

Photography has always been my refuge, a way to escape into a world I could create when the real one felt unwelcoming. I wasn’t always a photographer; in fact, I never saw myself as an artist at all. I was just a kid with an overly analytical mind, living up to the expectations of my Jamaican grandparents while feeling like the world wasn’t built to see me succeed. My brother was always the creative one—designing, drawing, and dreaming in ways I could never imagine. At 16, he was on our porch with his skateboard, all smiles, telling me about a T-shirt brand he was creating. He had borrowed my grandfather’s digital camera, hidden away in a closet, and asked me to take a few photos for him. I had just come off a grueling 16-hour shift slicing deli meat for $7 an hour. I was tired, but I agreed. That day, something clicked. The photos were far from perfect, blown out by the flash, the saturation cranked up way too high, but it didn’t matter. That moment was the spark I didn’t know I needed. The next day, I emptied my savings to buy a camera of my own.

From that point on, my camera was always with me. At 19, I didn’t call myself an artist, and I certainly didn’t think of my work as meaningful, I was just someone obsessed with the process. I started as an “adventure photographer,” sneaking into abandoned buildings, exploring forgotten places, or scaling scaffolding to get shots that were raw, grimy, and visually arresting. I had no real goals; I just loved the thrill of taking pictures and seeing the world come alive on a screen. I was lucky to have friends who were willing to keep up with my ideas, letting me photograph them wherever inspiration struck. For nearly a decade, I shot without narrative, capturing colors, faces, and spaces simply because I could. I didn’t understand it at the time, but those years were my foundation. I was learning how to see the world through my lens, but I wasn’t ready to look inward.

Then life started to crack. I’d always carried the weight of generational expectations, of trying to be great while brushing off the chains of my grandparents’ traumas. I thought ignoring it would make things better, that hope and optimism would be enough to keep me moving forward. But in 2022, everything shifted. I watched my grandfather have a psychotic break, screaming as he was taken away in an ambulance in front of our entire neighborhood. I sat on the steps of my apartment, and in that moment, I felt my soul leave me. I didn’t lose him physically, but I lost something else that day: my sense of control, my belief that life could simply be brushed off. I hit a breaking point I didn’t see coming. I stopped talking. I lost my voice. Photography became the only way I knew how to process the emotions I couldn’t name—the grief, the fear, the hopelessness.

In the years since, I’ve come to understand loss not as an isolated event but as an ongoing part of life. I’ve lost love, the kind that starts so beautifully but ends with two people bringing out the worst in each other. I’ve lost mentors who were like guiding stars and refused for so long to process their absence. I’ve lost the version of myself that used to believe the world was full of limitless possibilities. But even in those losses, I’ve found something else. There’s joy in the quiet moments I share with family, in remembering my grandmother dyeing her hair while sharing stories in her kitchen. There’s hope in revisiting the spaces that once brought me comfort and discovering new meaning in them. Photography allowed me to hold onto these fragments of life, both beautiful and painful, and piece them back together in a way that made sense to me.

The work I submitted is part of a project I titled “Kintsugi”. Inspired by the Japanese art of repairing broken pottery with gold, this series is a reflection of the beauty that exists in brokenness. Kintsugi doesn’t try to hide cracks or imperfections—it honors them, turning fractures into golden seams that make the object even more meaningful. That’s what I try to do with my photography. Each image tells a deeply personal story: rediscovery after losing love, yearning for unattainable moments, or finding safety in a familiar space during life’s upheavals. There are photographs of my childhood streets that remind me of skateboarding and dreams long forgotten. There are images of cold nights when I thought the weight of the world would crush me. There are moments of vulnerability, renewal, and resilience—snapshots of times I couldn’t handle but somehow survived.

I see myself as a photographer who embraces imperfection. My work is about honoring life’s fractures, the overlooked and forgotten parts of our stories, and the golden threads that hold us together. I try to capture the intimate, fragile, and honest moments that make us who we are. Whether it’s the quiet solitude of home, the strength found in memory, or the rawness of despair, I want my images to reflect the beauty in being both broken and whole. Through “Kintsugi”, I hope to show that our scars, no matter how deep, can be mended into something even more meaningful. This project is my story, pieced together through my lens, and it’s a reminder that there is profound beauty in embracing our imperfections.