Il Faut Que Les Braises De Constantinople S'envolent Jusqu'en Europe

-

Dates2021 - Ongoing

-

Author

- Location Türkiye, Türkiye

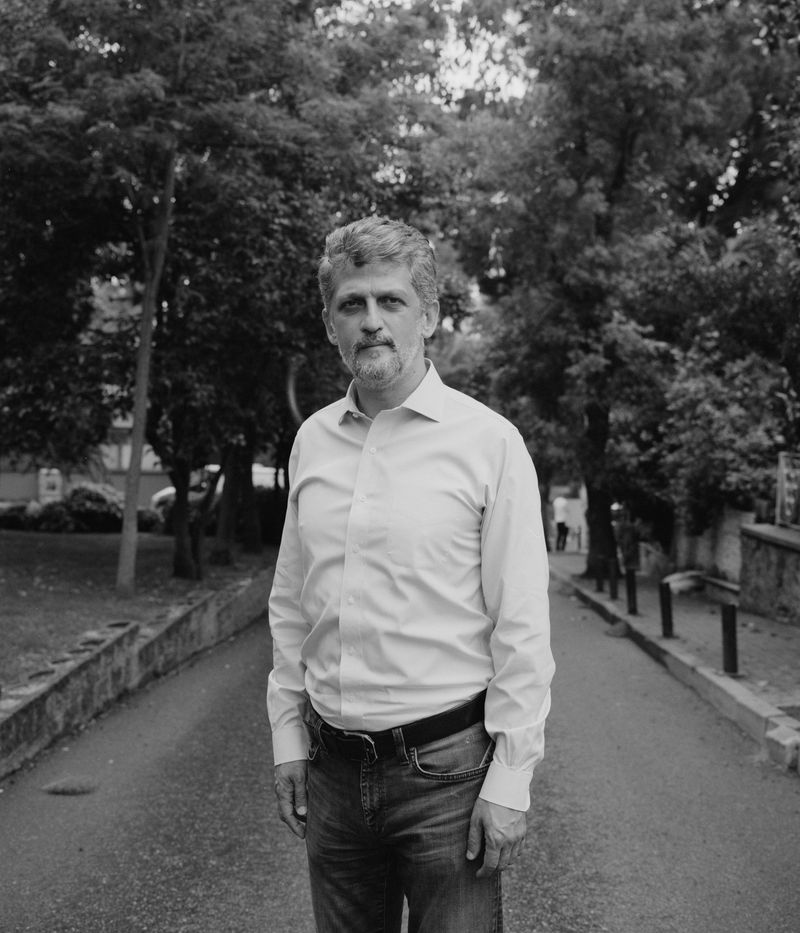

A photography project at the intersection of documentary and diary, about the Armenians of Turkey and the consequences of the genocide denial on people living in Turkey today, mixing my family history and today's experience.

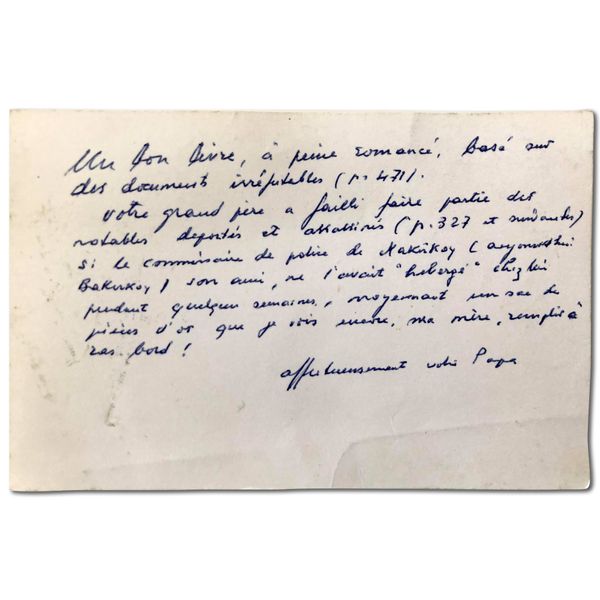

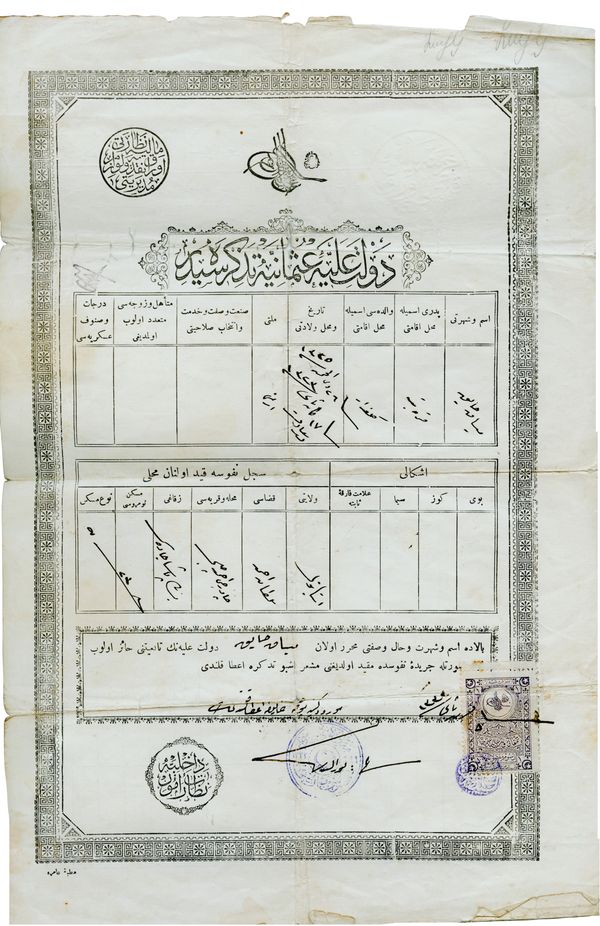

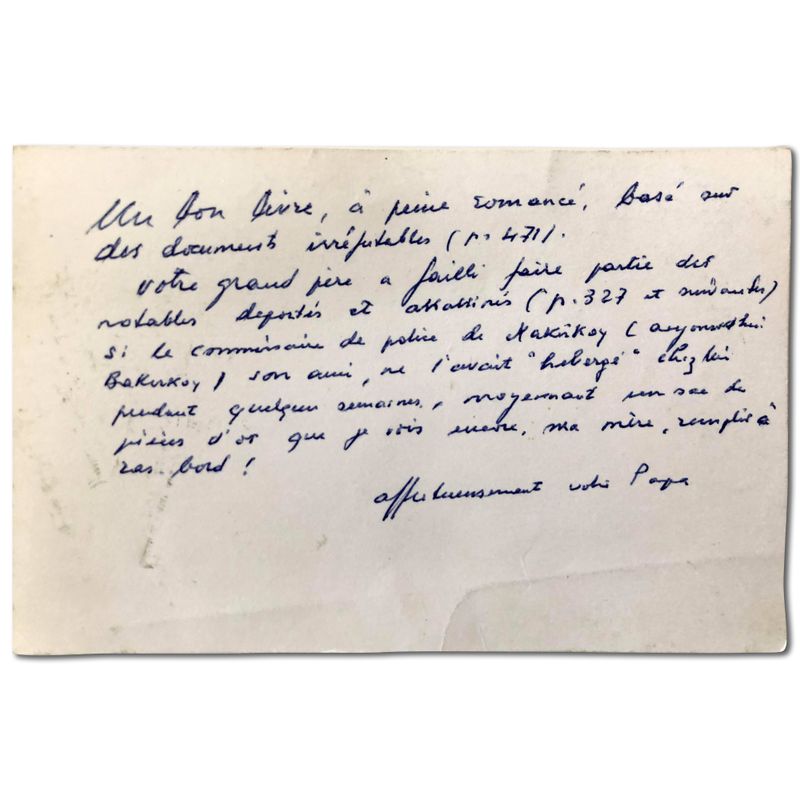

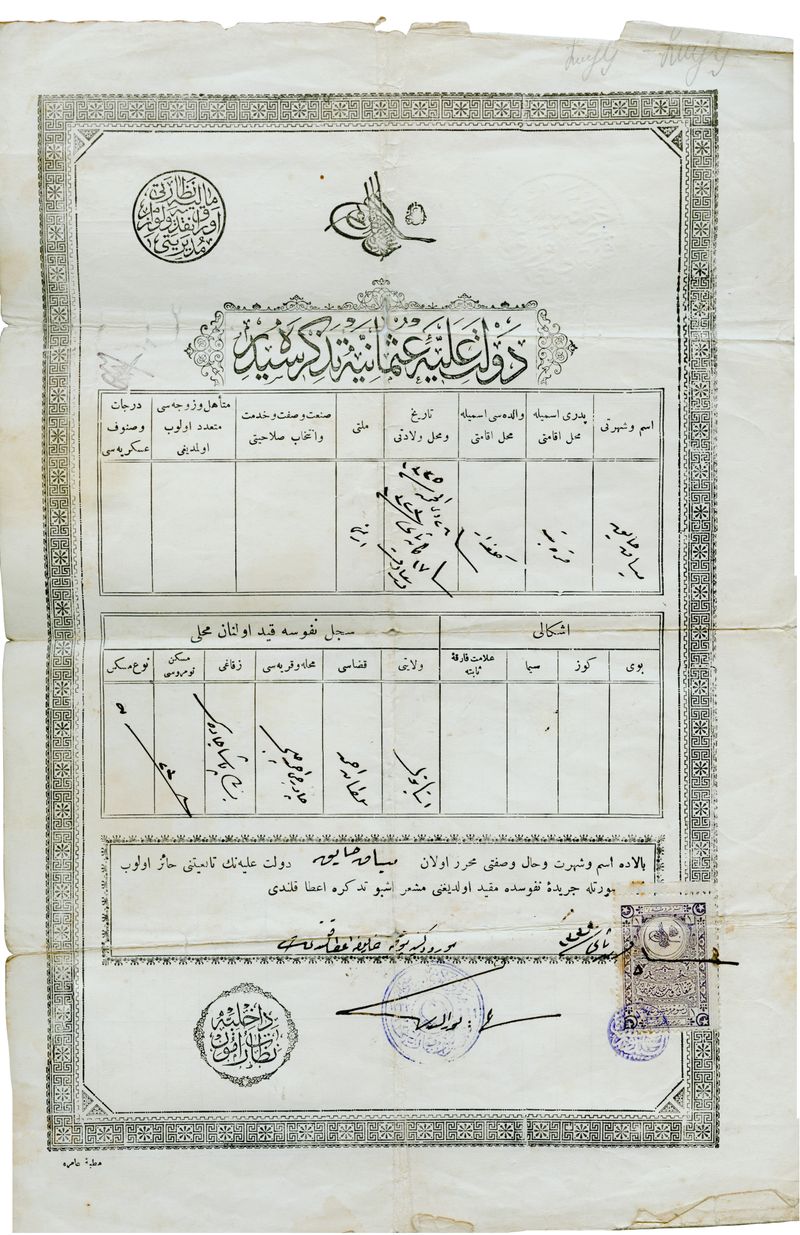

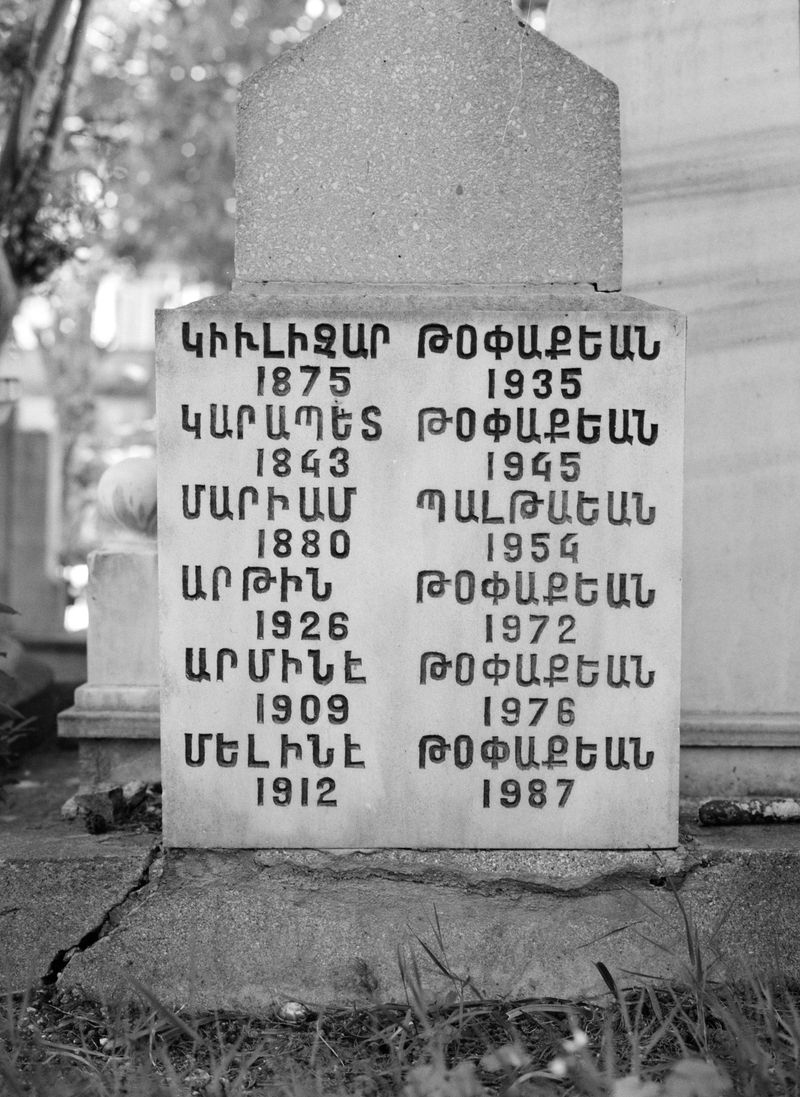

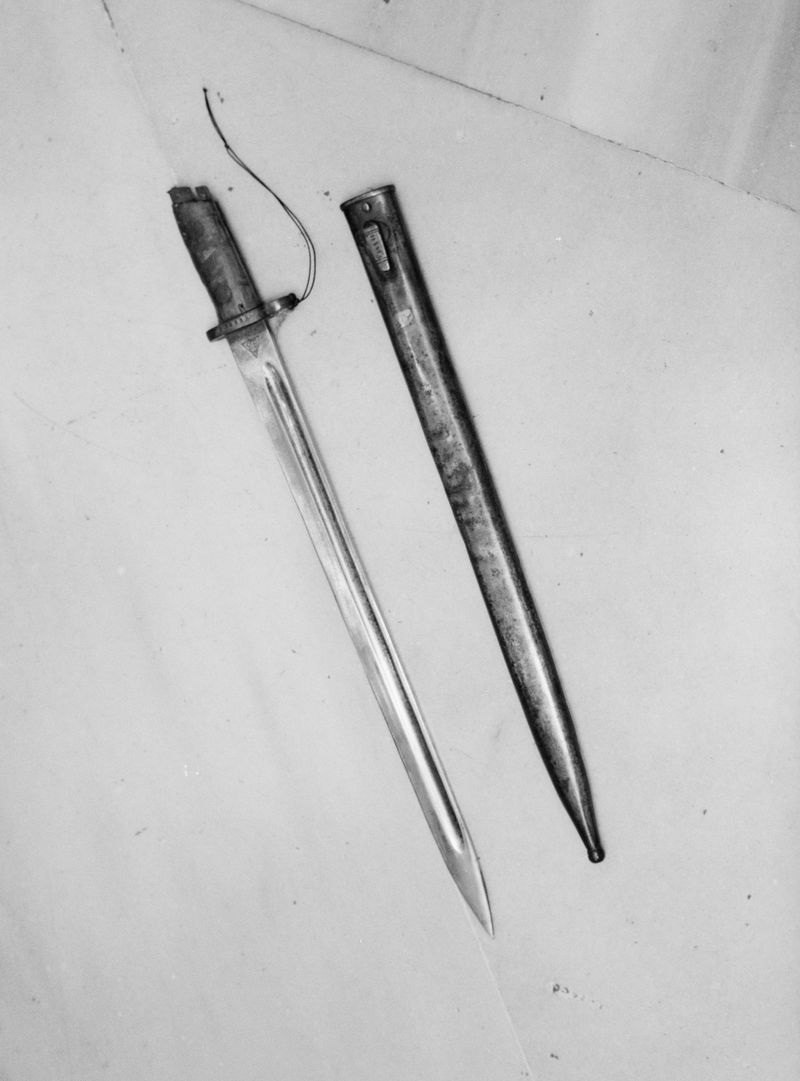

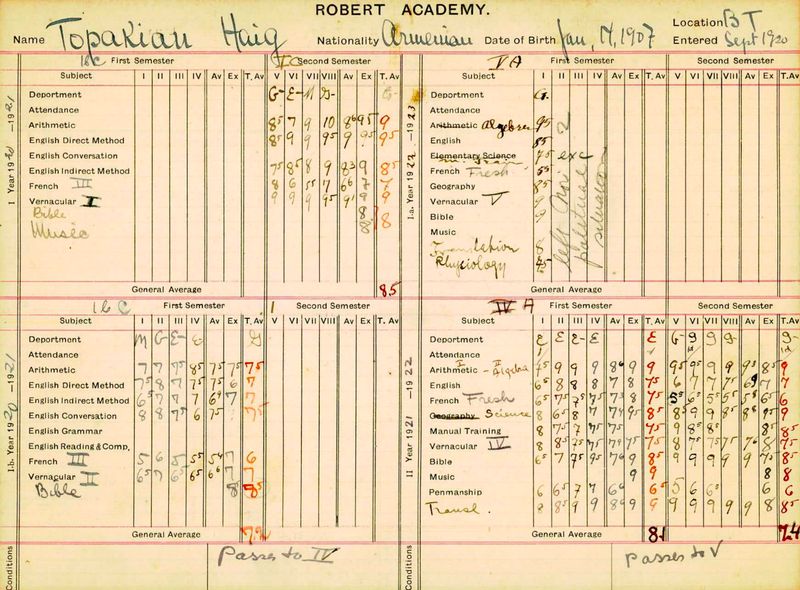

In 1922, my Armenian grandfather, a teenager, immigrated to France on a Nansen passport (stateless passport), fleeing the young Republic of Turkey where new massacres threatened the survivors of the Armenian genocide. Like many others of his generation, he passed on nothing to his children and never spoke of his experiences in Turkey, Constantinople and Talas in Anatolia. The only clue to his past is a note inserted in a novel about the genocide that he gave to his children (“Un poignard dans ce jardin”, Vahé Katcha), in which he reveals how his family survived.

Considering that the disappearance of family stories is one of the expected effects of genocide, along with the destruction of memory and culture, I decided to investigate my family's history on the spot and find traces of these people who were, for me, almost mythical. At the same time, I'm trying to understand the consequences of a policy of historical rewriting, denial and discrimination on Armenians in Turkey today.

Deprived of freedom of expression, imprisoned or murdered when too vocal, Turkey's Armenians are little heard and therefore often forgotten. Their history and stories, however, represent in the extreme the experiences of minorities in Turkey today and reflect the ambiguity of a policy that hides racism under assimilationism. Above all, it's a particular feeling in everyday life: as the only genocide not recognized by its perpetrators to date, state negationism has diffuse consequences for everyday life and psychology. How does it feel to live in a country whose national hero is a criminal? When streets and schools bear the name of one of the architects of the genocide? When the president himself calls you a “remnant of the sword”...

Through the prism of my personal story and my exploration of my family history and the territory of Istanbul, the aim is to capture something of the diffuse feeling of living in an environment where your history is denied.