Hypersea

-

Dates2024 - Ongoing

-

Author

Hypersea is a speculative exploration of the porous boundaries between humans, animals and the natural environment, starting from the transformations imposed on my body by a rare degenerative disease.

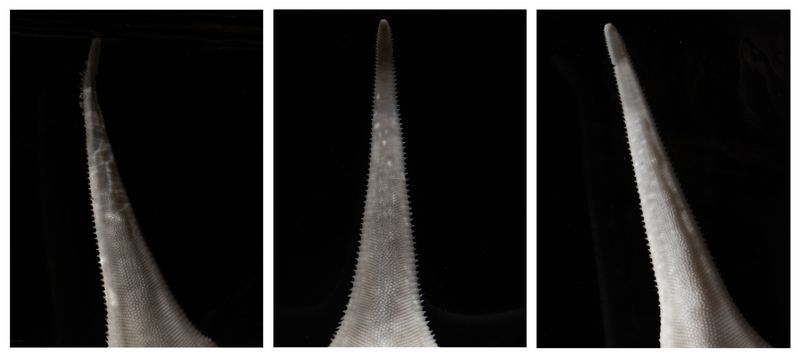

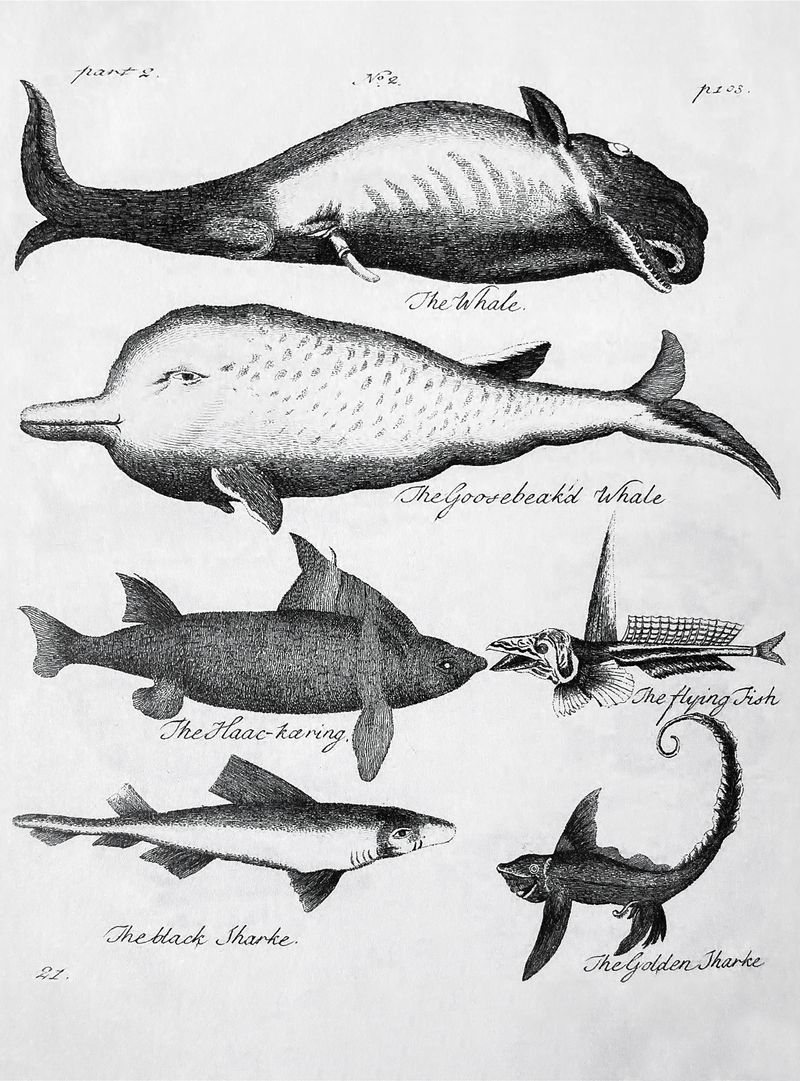

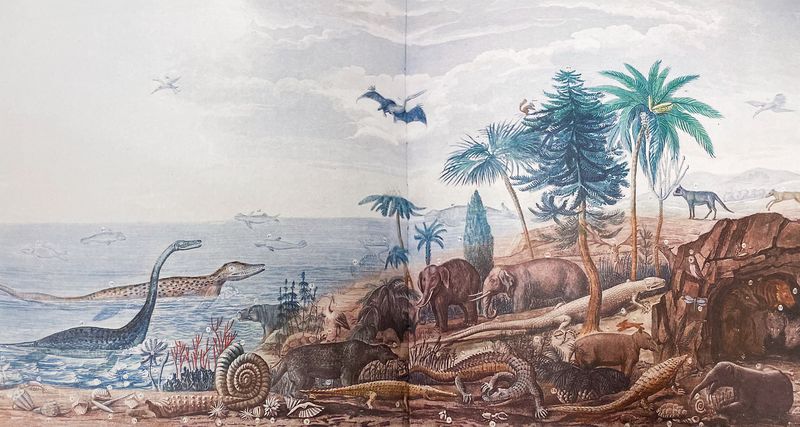

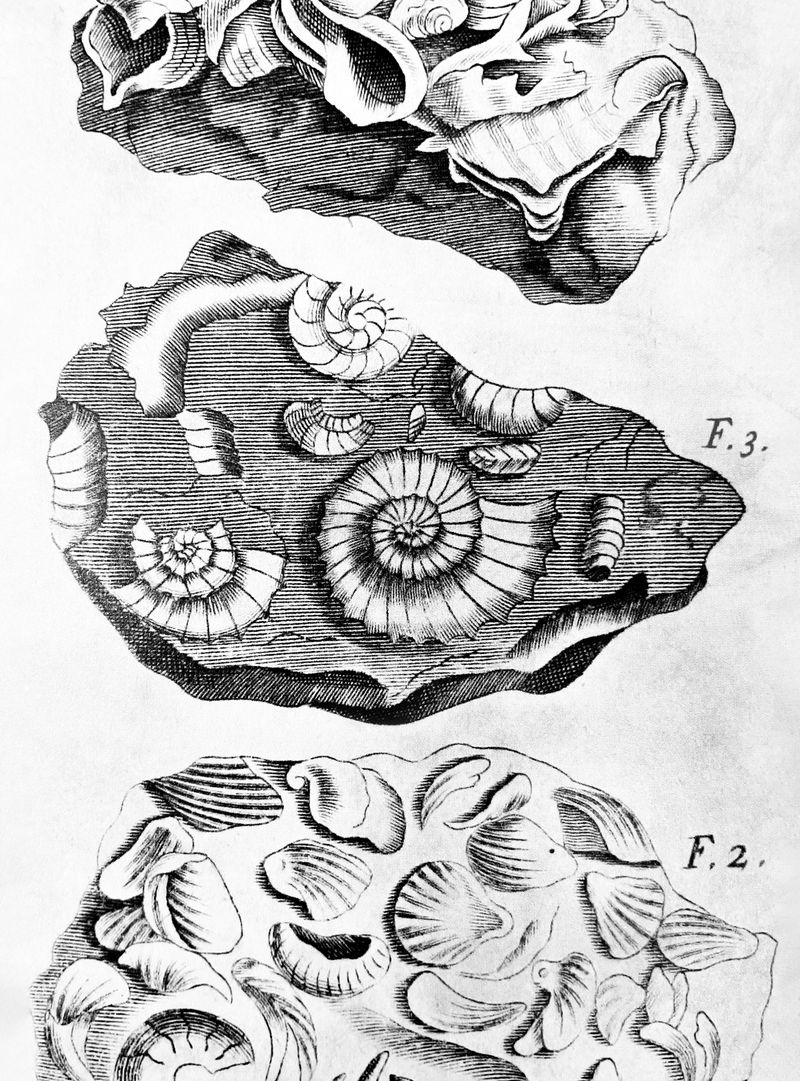

The project intertwines the cyborg body and movement with the numerous forms of life in the ocean, examples of regeneration, community life, care and survival strategies. Through a reflection on the Edge as a Space of Resistance - understood, in Bell Hooks’ vision, as a place capable of offering us a radical perspective from which to look, create, imagine alternatives and new worlds - this work investigates the infinite space of creation that can arise from feeling trapped in one’s own body. The evolution of marine mammals becomes a key to understanding the similarities between humans and the animal world, in a journey that extends from anatomy to prosthetics as an extension of the body, from anthropomorphised landscapes to steel structures that simulate tentacles, to the creation of a hybrid being, half woman and half animal. Water becomes a metaphor through which to reconfigure care, interdependence and identity. Hypersea shapes the body not as a place of limitation, but as a generative terrain for rethinking corporeality, presence and our place within a more than human ecology. The project includes a kinetic aquatic installation and a transparent resin sculpture, in dialogue with photographs and video performances created during an artistic residency at the Italian Cultural Institute in Stockholm.

Video performances can be viewed here:

1. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Srv7rzj2g7E&t=7s

2. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aF-72-Hs4HA

Kinetic installation here: https://youtube.com/shorts/xWsWRyhygVU?si=PzOuItIZR9G-PUcR

Project commissioned and promoted by the Italian Cultural Institute in Stockholm in collaboration with the municipality of Reggio Emilia and with the contribution of the Directorate-General for Contemporary Creativity of the Italian Ministry of Culture.