How To Tame A Wild Tongue

-

Dates2025 - Ongoing

-

Author

- Locations Morocco, Rif

How to Tame a Wild Tongue confronts the silencing of Tamazight by colonial assimilation and cultural erasure. Using fragments and absences, the work forms a counter-archive of endurance and survival.

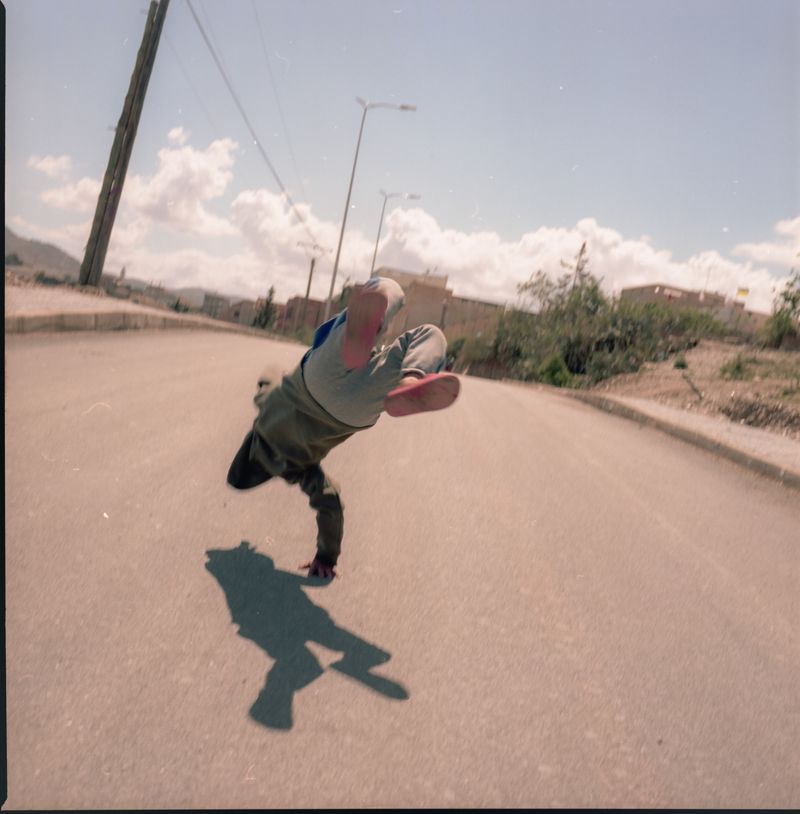

Tamazight lives in my mother’s voice, but no longer fluently in mine. At the age of ten, I let go of my ancestral language without knowing it would remain with me like a shadow… a silence that has shaped my identity as much as any word I learned to speak.

This project begins in that silence and moves outward into history: Born in the Netherlands to Amazigh parents, I grew up fluent in the languages around me yet distanced from my own. That loss is both intimate and structural: a result of colonial systems that fractured generations, reshaped language use, and left lasting traces on cultural expression.

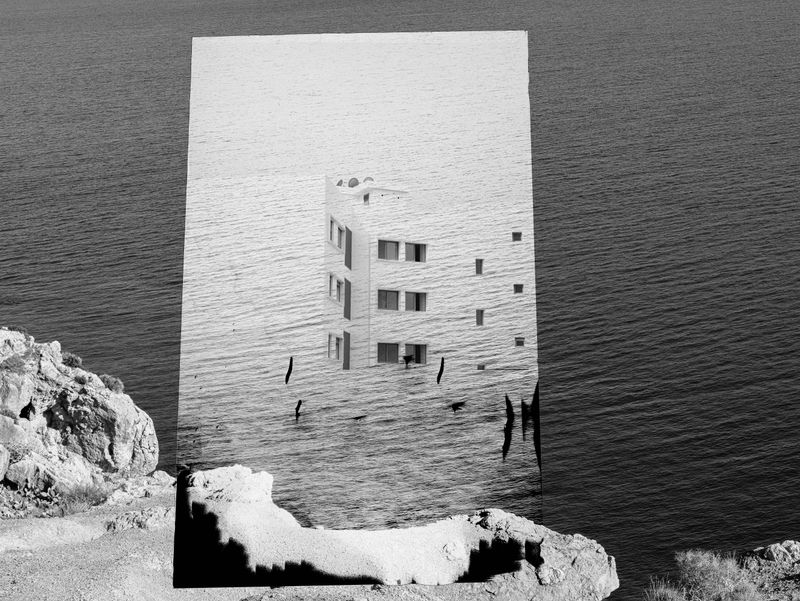

Like a language quieted, a memory can be erased, overlooked, or reshaped (not only through forgetting but through historical circumstances that limited its visibility).

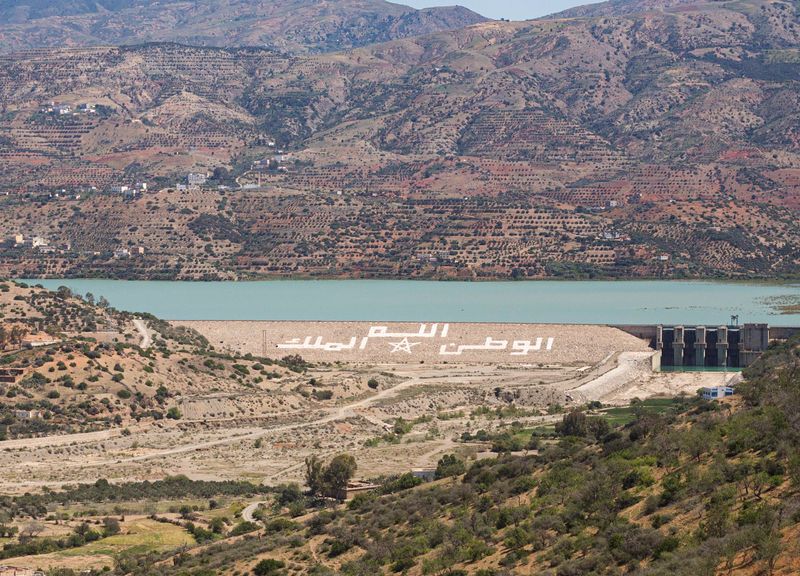

In Morocco, Tamazight held a reduced role in public life for much of the twentieth century: it was largely absent from schools during French and Spanish colonial administration, and was formally recognised as a national language in the 2011 constitution. Implementation has continued gradually across public institutions and educational settings.

These histories of silence shape both public life and private experience. My family left Morocco within this broader context of social and economic difficulty. I inherited Tamazight not as fluency, but as interruption; a quietness that unsettled my sense of belonging and eventually became central to my work.

How to Tame a Wild Tongue gathers fragments of memory, erased slogans, unfinished houses, and landscapes marked by absence to form a counter-archive. Rather than restoring what has been lost, the project embraces incompleteness as a form of persistence, insisting that what remains - fractured and fragile - is still alive, still meaningful, still carried forward.