How to eat at night

-

Dates2023 - Ongoing

-

Author

A photographic inquiry into the militarized power of narrative—where regimes engineer myths to command loyalty, collapsing memory into obedience and leaving identity suspended between dream, illusion, and control.

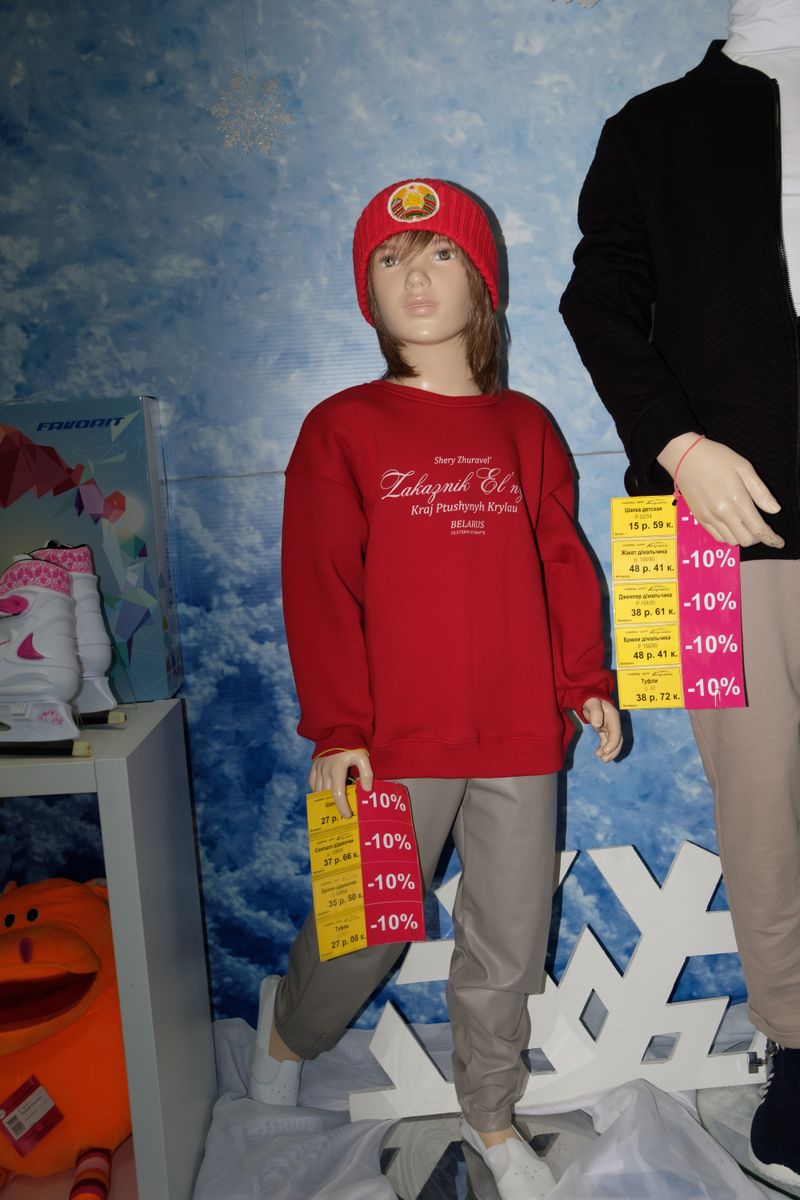

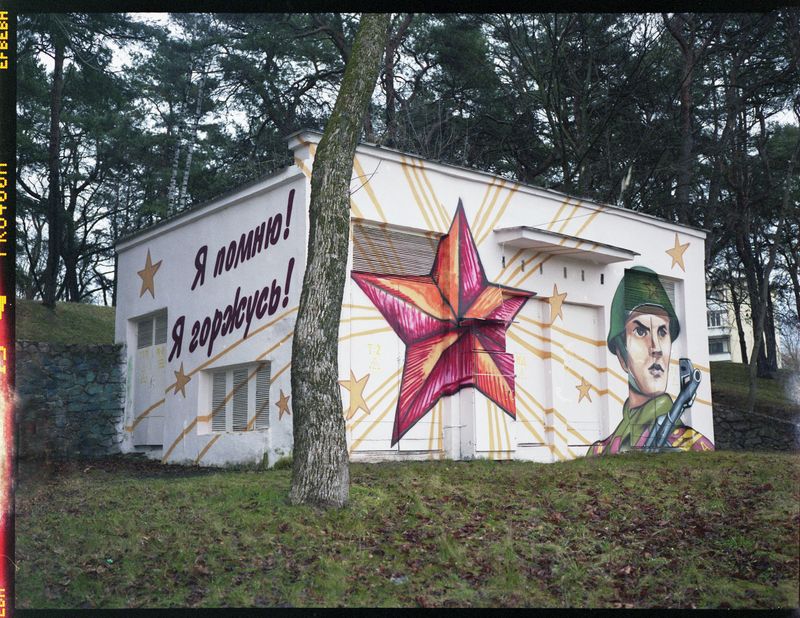

In societies shaped by ideological regimes—like the former USSR or modern-day China—fairy tales are not inherited but engineered. They are illusions built to soothe, distract, and control. On the surface they appear vivid, even beautiful—but with the lightest touch, the seams begin to loosen.

My ancestors came from Ukraine, Belarus, and Russia—across borders that shifted faster than the stories that tried to fix them. Under the Soviet regime, these layered identities were collapsed into a single, approved narrative. I grew up inside that version of the world—comforted by its clarity, yet always aware of its silences.

The story continues. In Belarus—my motherland—the symbols have been updated, but the rhythm is unchanged. Returning there feels like waking inside a dream still being told: streets slightly misaligned, meanings subtly rearranged.

This work explores that dissonance—between memory and invention, between the personal and the prescribed. Like Andersen’s fairy tales, beauty and unease walk side by side, and even memory becomes unstable. Propaganda today is more polished, but no less present. For those raised on borrowed myths, identity begins in uncertainty. The project does not offer conclusions; it lingers in doubt, quietly asking: what if the story isn’t true?

Media and structure

Photography within the project unfolds across different registers: some images remain straight and unmanipulated, others are reassembled into collages from my own photographs, while another direction produces uncanny pictures that appear almost AI-generated yet come directly from the camera. This tension between the documentary and the illusory mirrors the strategies of propaganda itself, where reality is presented with the authority of truth but carries within it the possibility of distortion. By inhabiting this fragile space, the photographs challenge how we see, what we believe, and how easily vision can be persuaded.

This work includes a wooden fence-like object (70 × 90 cm) with a photo transfer depicting ordinary citizens and everyday symbols of the country; a video (https://youtu.be/6J8oA09_P9U?si=L4Ppz__0uLMovSV7) where propaganda hides in plain sight, streaming through state channels even under the guise of nature; and a sound work (https://youtu.be/V4BZRgBLYHU?si=v03ztwokBTcvppvJ), in which a Belarusian recipe for draniki is encrypted in Morse code and overlaid with digital notifications—tradition disguised as signal, echoing the paranoia of authoritarian control.

Together, these elements form a fractured narrative where everyday gestures are charged with suspicion, and culture survives only in encrypted whispers.