Before you stand

-

Dates2024 - Ongoing

-

Author

- Topics Documentary, Fine Art, Portrait

- Location Sesto San Giovanni, Italy

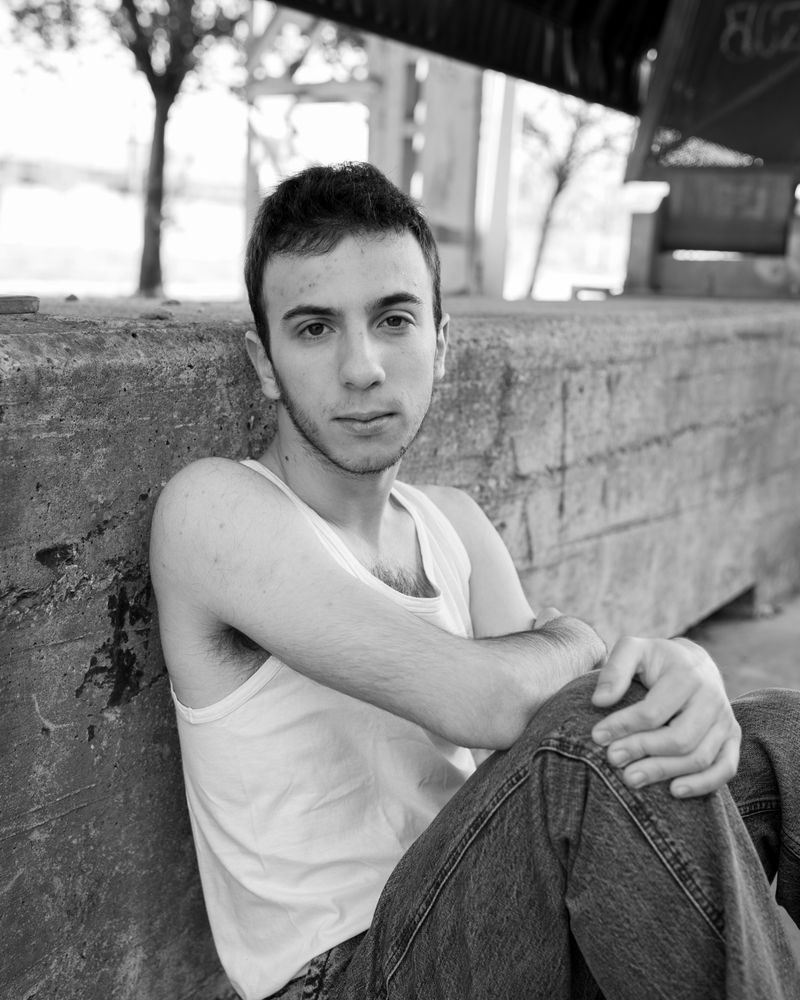

In the quiet hours of a concert arena on Milan’s outskirts, young people arrive each day: some pause briefly, others remain. Here, being present does not mean being seen. This is why I continue to return.

The Carroponte of Sesto San Giovanni lies on the northern outskirts of Milan.

Originally part of the Falck steelworks, it is a vast post-industrial structure built for the handling of heavy materials and converted in 2008 into a concert venue.

Anyone who grew up here knows it for what happens at night. During the day, however, the place changes completely. Stripped of its spectacular function, it becomes almost entirely empty: a large urban space where stage equipment and metal frameworks coexist with silence and the absence of an audience.

It is during these hours that young people arrive. They sit, lie down, lean against the structures. Some pause briefly, others spend entire afternoons.

Why here?

It is not a place of leisure like a park, nor the noisy crossroads of a square where people usually gather. And yet, day after day, it is inhabited — away from the structured gaze of the adult world and from group dynamics.

I was born in a city where the industrial landscape never truly disappeared, continuing to shape ways of living even after the factories closed. This led me to reflect on the gap between the legacy a place carries and the way young people reshape it through their presence and use.

By day, the Carroponte becomes something else: a residual space that, away from the spotlight, young people choose to make their own.

This ongoing series of intimate portraits emerges from proximity — from a quiet relationship with the people and with this place I continue to return to.

NOTES ON THE PLACE

The Carroponte in Sesto San Giovanni is a former industrial structure of the Falck Steelworks, originally built as a large metal gantry for moving heavy materials. A historical landmark of the workers’ movement in a city once nicknamed the “Manchester of Italy,” it was decommissioned at the end of the twentieth century and transformed into a cultural and music venue in 2008. Today, Carroponte is one of the main open-air arenas in the Milan area: during the summer season it hosts concerts and festivals with a capacity of up to 12,000 people. During the day, however, the place remains almost completely empty: a vast suspended urban space where the stage infrastructure and metal framework coexist with silence and the absence of an audience.