Cuevas de Sacromonte

-

Dates2024 - 2025

-

Author

- Location Colombia, Colombia

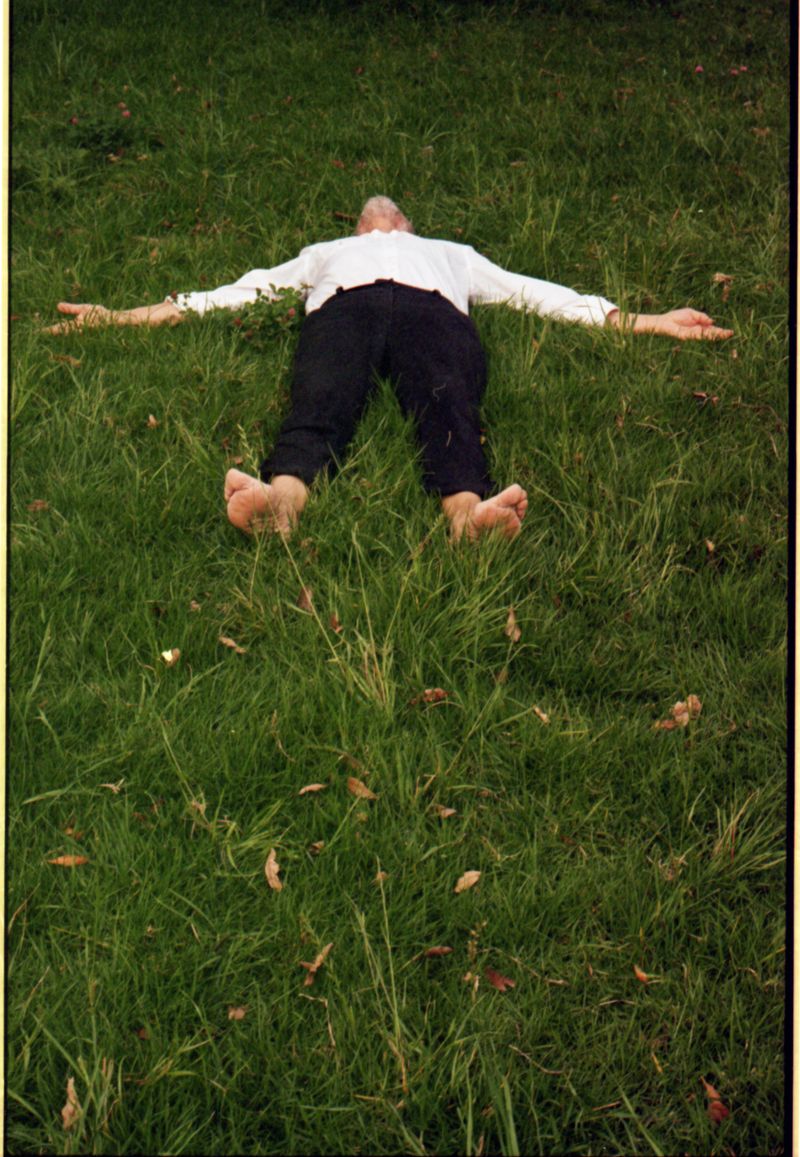

Set in 1970s Colombia, a father exiled after torture and false accusations, a daughter left in absence. This project revisits their broken bond through experimental image-making, where archive, pixel, and the crack become tools of memory.

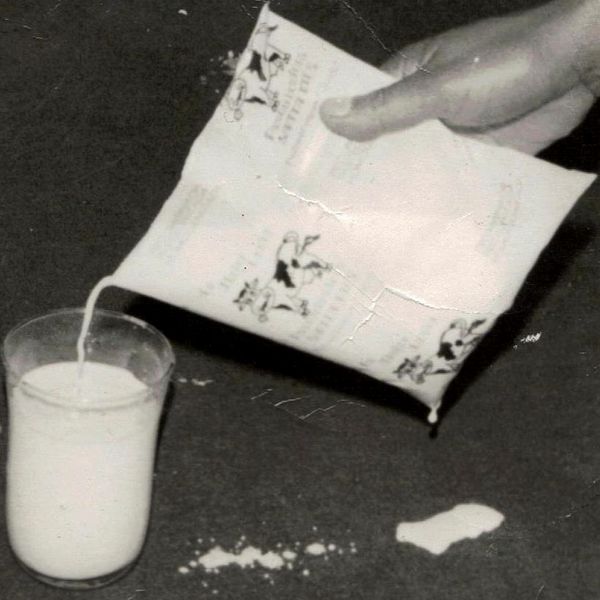

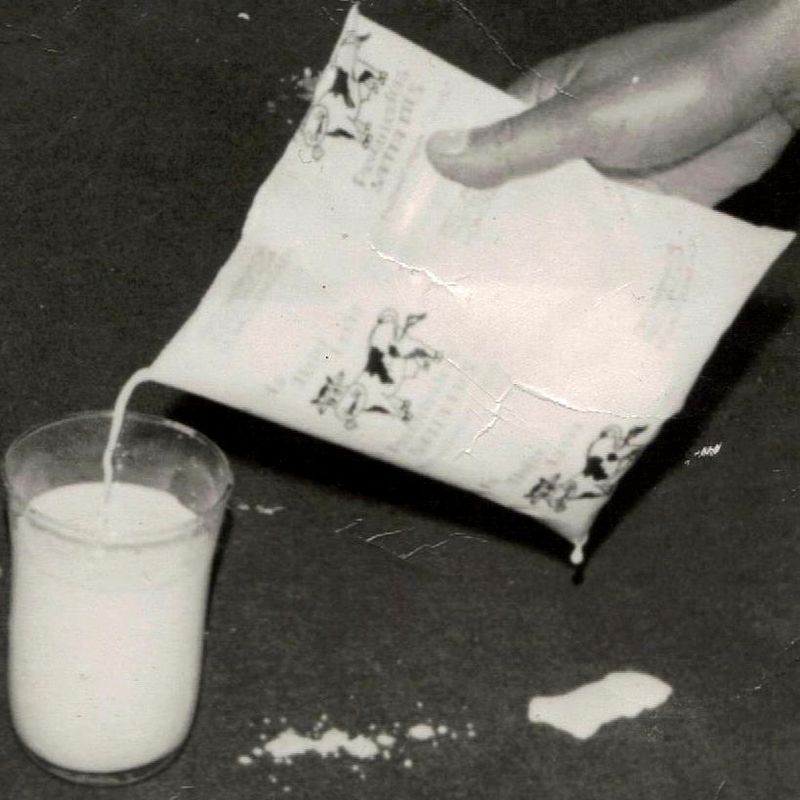

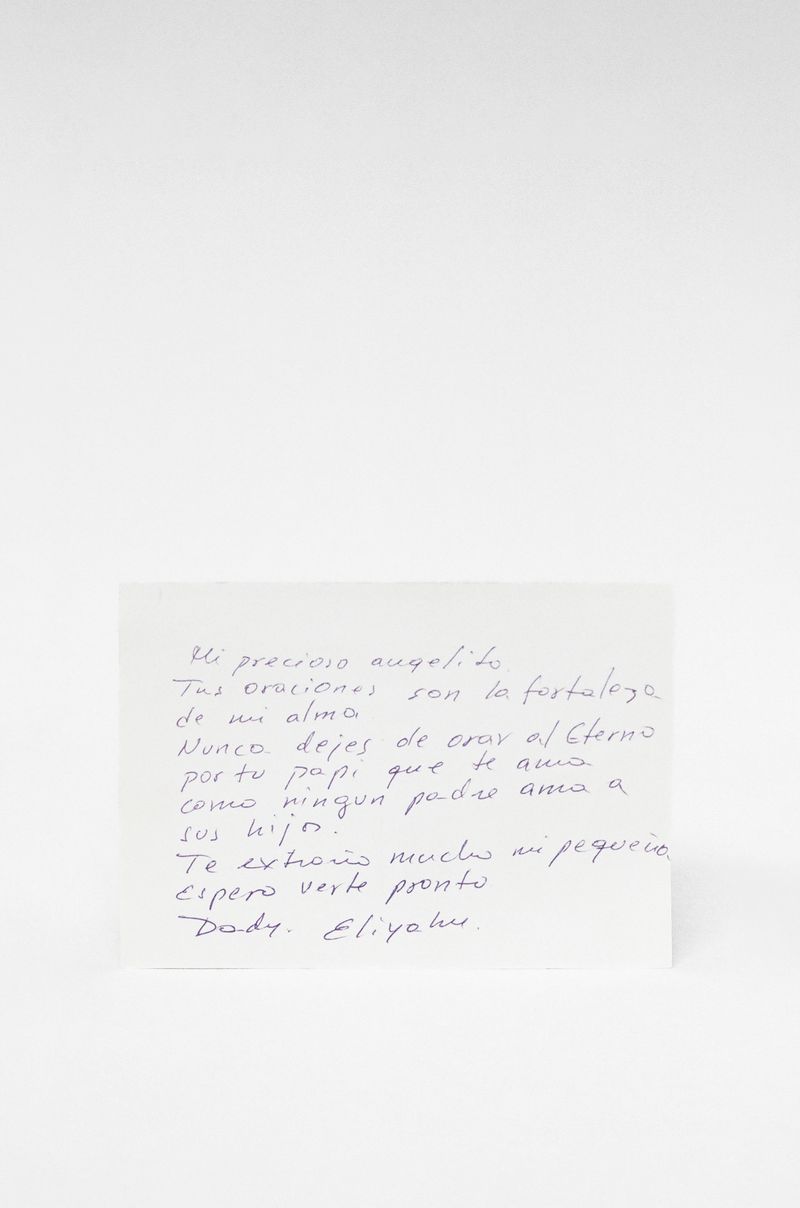

In the 1970s, amid political unrest and escalating violence in Colombia, my father — a journalist and director of an agricultural magazine — was falsely accused of the assassination of the Minister of Agriculture. What began with his torture ended in his exile and more than 15 years of separation from our family.

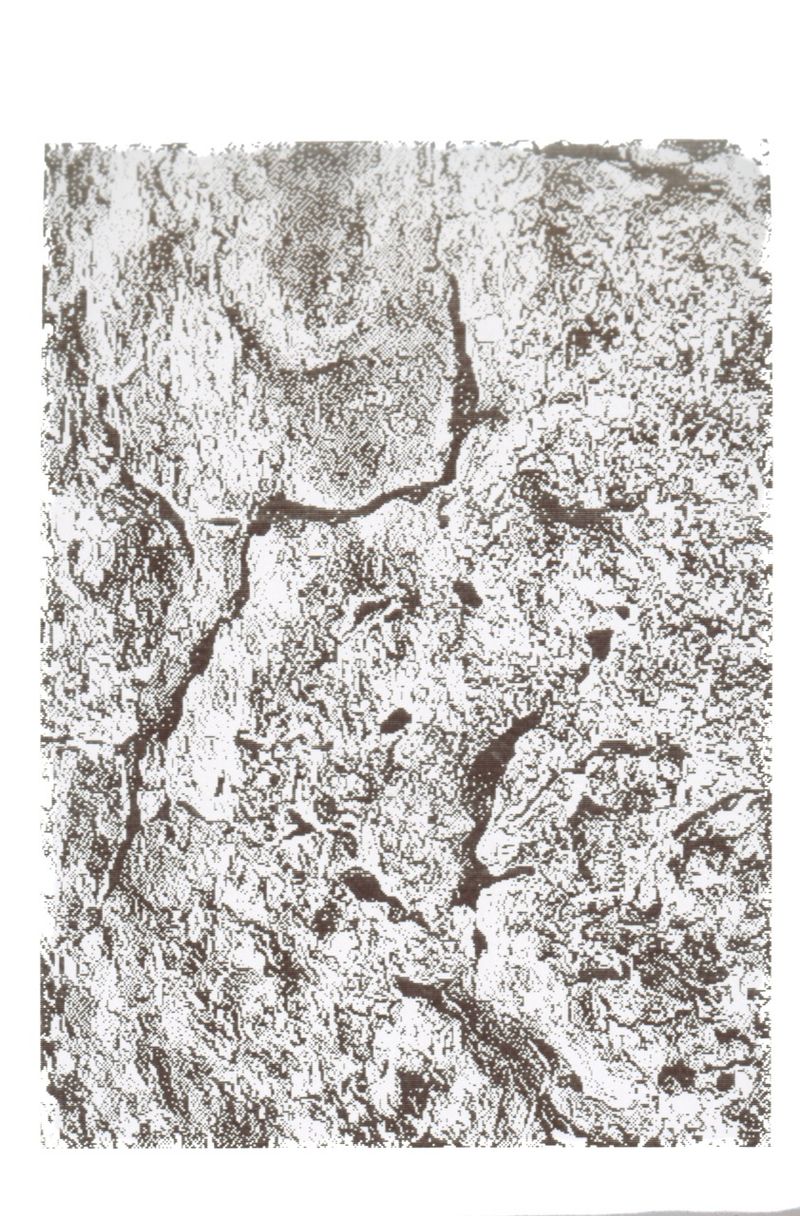

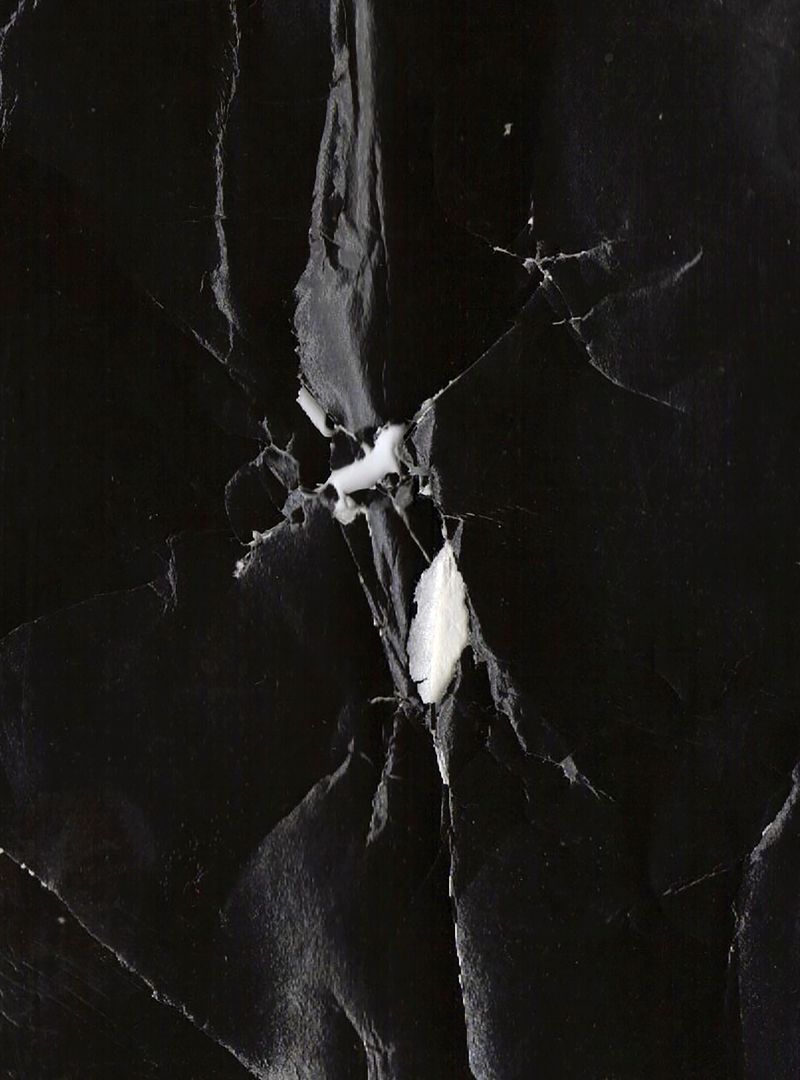

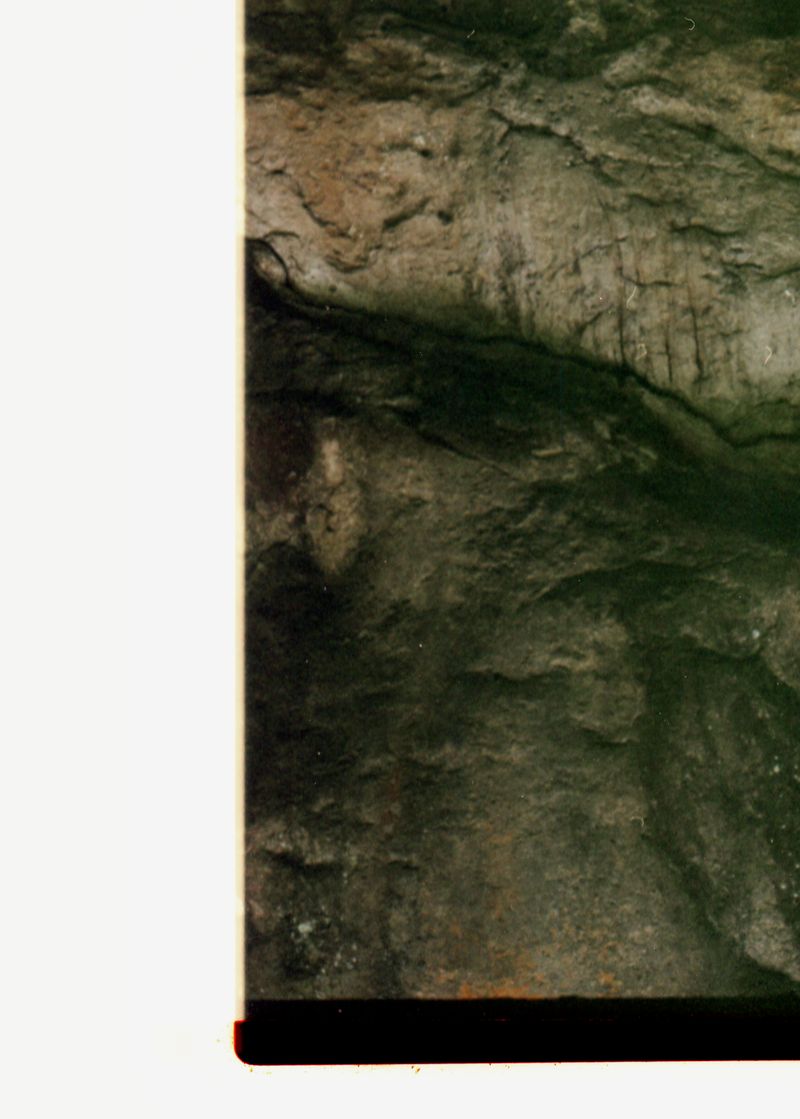

Cuevas de Sacromonte emerges from that absence. Borrowing the name of a site once used as a torture center on the outskirts of Bogotá, the project reconstructs the interrupted bond between father and daughter. Through photography, archives, and staged gestures, I explore how absence itself becomes a material: a fissure where substitution of characters, re-imagined spaces, and manipulated images become strategies to narrate what was missing.

From Latin America, this story does not seek to contain a single truth and, rather than focusing solely on violence, it seeks to reclaim silence and emptiness as forms of presence. It proposes a new way of telling our stories, one in which intimate wounds open a collective dialogue about absence, presence, pain, and identity, transforming silence into another form of testimony.

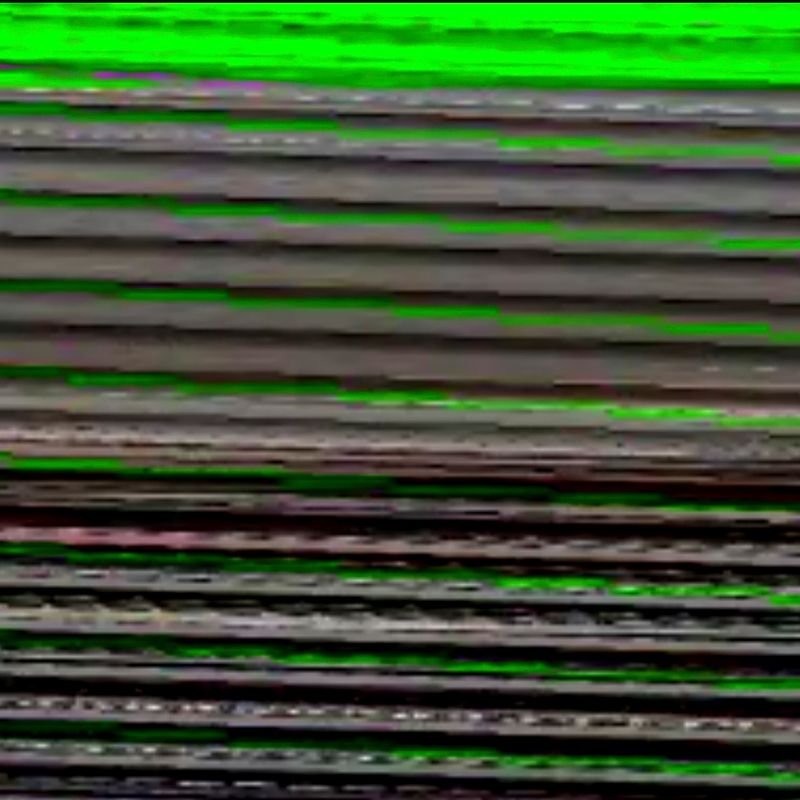

This project unfolds through a photobook, an exhibition, and an audiovisual piece that explores the crack into expansion:

www.perlabayona.com/cuevas-de-sacromonte-video

The photobook is structured in three chapters, tracing key personal events: the bombing at the magazine and kidnapping at Cantón Norte; exile to the United States and the mediation of presence through boxes and screens; and finally, the reunion that heals, yet opens another absence. The selection currently includes around 50 images with testimonial texts from the Comisión de la Verdad, an institution dedicated to documenting the country’s armed conflict. These texts provide additional context, allowing the work to transcend the personal and connect with broader social realities.

The photobook mockup:

www.perlabayona.com/cuevas-de-sacromonte-photobook-mockup

If awarded the grant, the funds would support the production of a limited edition of the photobook (e.g., 500 copies), consolidating the narrative and conceptual structure of the project. Also, since this is not only a photographic project but also an artistic one, where different techniques are explored, the participation in portfolio reviews and the potential exhibition at PhMuseum Lab would provide invaluable feedback, and visibility, enriching the work both artistically and conceptually.

As a young Colombian woman and migrant in Spain, I approach this project not only as an artist and photographer but as someone tracing the echoes of her own history. While my work has long engaged with social issues, this is the first time I give voice to my personal story, and to my father’s, whose absence was long normalized in family albums and through the stories of my parents. Living as a migrant has also allowed me to revisit and understand his exile in a new light. So, this project is not merely about recounting events; it is an active exploration of how personal absence can be interpreted, reshaped and mediated by many factors...finally, creating an ever-evolving new form of reality.