The Most Familiar Life

-

Dates2025 - Ongoing

-

Author

- Topics Daily Life, Documentary

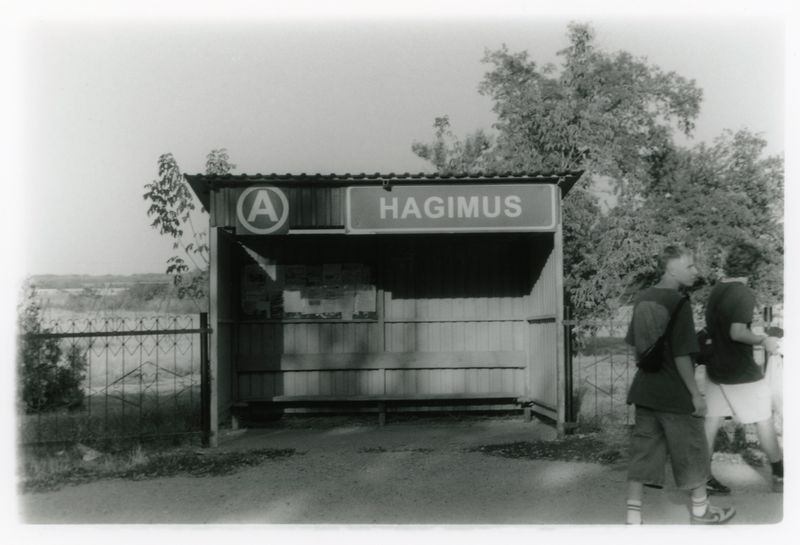

- Locations Tiraspolul, Chișinău, Administrative-Territorial Units of the Left Bank of the Dniester, Hagimus

In Transnistria, the questions I asked others about home, belonging, and why they remain were the very questions I was asking myself. What began as interviews became a mirror, revealing that I was searching for my own answers through them.

The Most Familiar Life is a long-term documentary project that began in Transnistria, a self-proclaimed state along the Dniester River that remains unrecognized internationally. If someone were to ask why I came here, the answer would not be a simple explanation but a question that inevitably returns to myself: Why am I here? What brought me to this border? Interestingly, many of the people I met asked me the very same questions. And I realized that their questions were also my own.

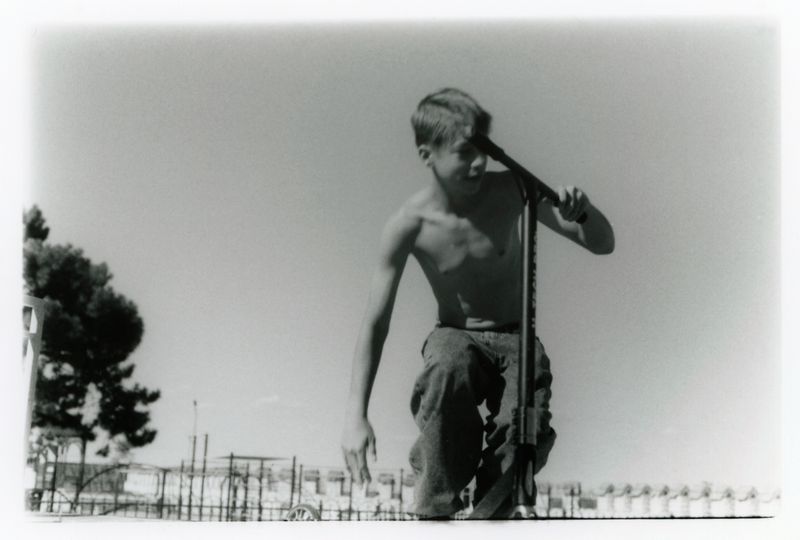

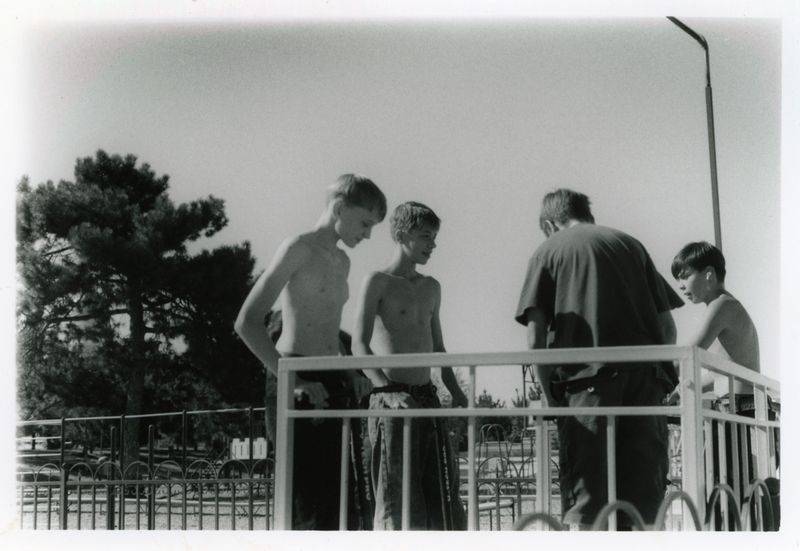

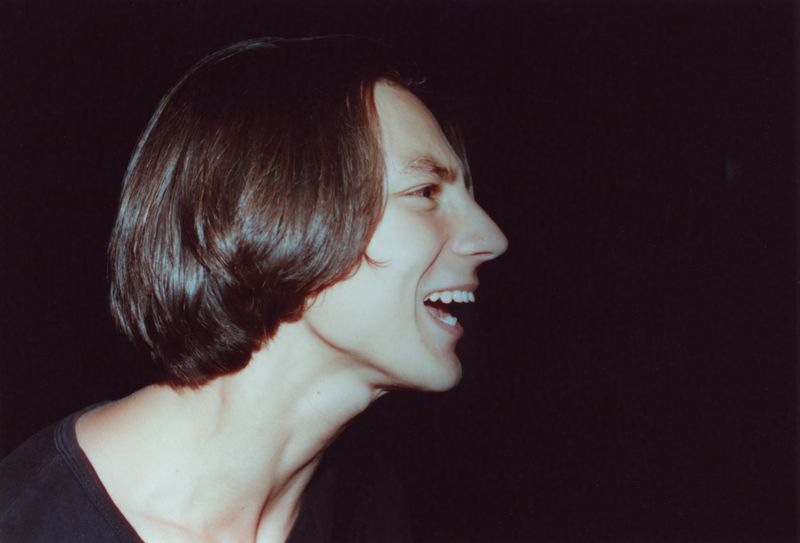

I learned how to navigate this place by listening to people’s lives and accepting the invitations that appeared by chance. One day I was invited into a home where I ate grapes and drank wine. On another, I joined a small local festival in Hagimus, a village situated along the Moldova–Transnistria border. In an apartment complex I met a boy carrying a guitar, and together we spontaneously filmed a music video. My work does not begin from fixed plans; instead, it finds its direction through encounters like these. The act of recording here was never about proving something but about the slow process of understanding.

I asked young people I met, “Do you think about the future?” They carried both energy and uncertainty. Some released raw intensity in heavy metal bands. A sixteen-year-old boy named Max told me in Russian, “Life in an unrecognized country is difficult, but it also makes me happy.” I only fully understood his words after translating the audio, and they have stayed with me ever since.

Growing up in South Korea, a divided nation where I never directly experienced a border, the idea of a frontier existed only in my imagination. I often wondered what kind of culture is shared across a border, how people are different or the same, and whether a line on a map could really divide life so precisely. This was why I expected that living near the Moldova–Transnistria border, and in a country unrecognized by the international community, would feel unique or exceptional. Yet when I asked young people about their hopes and fears for the future, their answers were not so different from those of my own friends back home: uncertainty about jobs, the desire to leave balanced by reasons to stay, the tension between possibility and limitation. In their voices I did not hear “a special problem of a special place,” but the same generational concerns that echo across the world.

From the perspective of outsiders, Transnistria appears unrecognized, undefined, and almost erased from the map. But for those who live there, it is simply everyday life. As I left Transnistria on a night train from Moldova to Romania, I met a family who invited me to visit their home. They showed me a sentence on a translation app: “Our town is close to Romania. From the edge of our garden you can see the border.” In that moment I understood once again: a border is not only a distant geopolitical structure, but also a view from someone’s backyard.