Arder la casa, on political violence, family and exile.

-

Dates2021 - Ongoing

-

Author

- Location Colombia, Colombia

The saying is that to remember is to go back through the heart. Memory is malleable, fluid, mutates with our experiences, and becomes a story, a narrative. Each of us influences the way we remember; we discriminate and choose the details that impact us the most from experience. Reviewing a memory is an act of imagination and performance. Each time we go through a memory again, we modify it with our closest experiences, adapting it to our new way of seeing reality. Remembering also helps us understand the past from a new perspective, perhaps with more information, revealing previously hidden layers.

I remember it was a summer night on my father's farm. It must have been seven or eight o'clock at night, but the penetrating darkness of the field and the lack of electric light in the surroundings gave the feeling of a late night. My brother, a couple of cousins, and I were there, all of us kids, enjoying summertime. We sat down to play at the cement table, a long, wide, grey, cold, strong table that my grandmother had built a couple of decades ago to accommodate lunch for all the workers on her coffee farm. Since the table was made for adults, like most dining tables, we sat on it with our feet dangling into the void. We had a lego box, with five hundred or so tokens, of many colours and shapes, and we spilled all the tokens across the table. My memory is fuzzy. As we explored the tokens; we put together ships, houses, and castles. Suddenly, one of the tiles fell to the floor under the table, and one of my older cousins got down from the table to pick it up. -A tarantula! he shouted. -Uncle, uncle, uncle, a tarantula!. I didn't know what a tarantula was, but I imagined it was something colourful, similar in shape to one of the legos I was playing with. I got down from the table and sat down on the cement chair, and from there, I tried to look for the tarantula. I saw nothing. Under the table, there was only darkness, dust, and nothing else. I looked everywhere as long as possible, but the adults immediately commanded me to run into the room. Tarantulas were poisonous, I learned. I waited until they managed to capture it in a dustpan, and I approached it again, "Look at it," said my cousin. I looked, but I couldn't see anything, I saw dust and dirt, but I didn't see the tarantula. -I don't see anything; where is it? I asked -there it is, don't you see it? You are blind!. I was confused. I rubbed my eyes and asked -What do tarantulas look like? Well, they are grey, dark, have many legs, and a hairy body. Uhh, they are ugly! My cousin said. My father took the dustpan and the tarantula and walked away. I ran behind him and asked him to show me the dustpan again -Let me see it, I want to see it again. I yelled. -That's enough, he replied. And left with the animal walking into the forest.

That night, playing Legos with my cousins, I couldn't see the tarantula, and I couldn't remember it because what I imagined looked different.

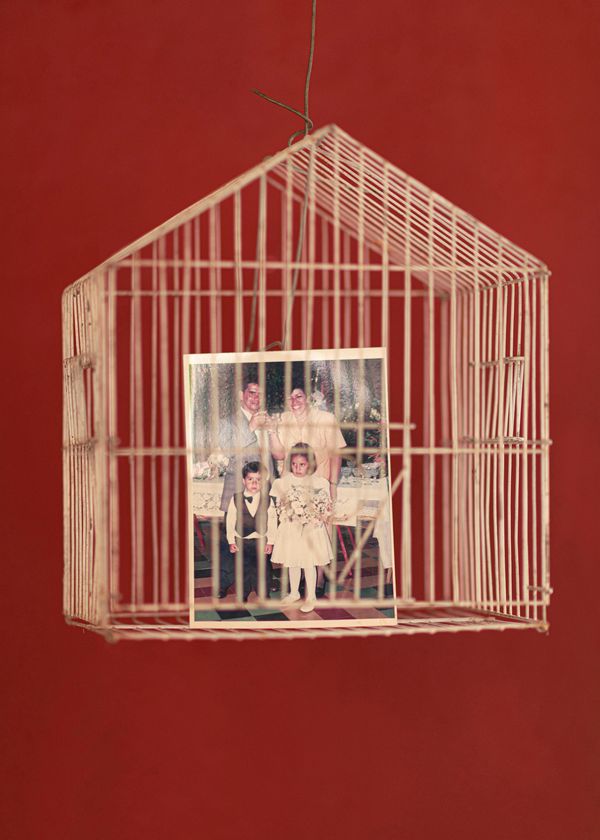

Something similar happened when I forced myself to remember my family history. I could not form a visual composition, nor a general overview of it, given that I knew the story by parts, fragmented. I was familiar with just the side of the story that my parents had shown me. What I had normalised before, what felt like an alright world then: the absences, the silences, and the distance, which were part of our family culture, now became unbearable. Absences now made me uncomfortable, and the feeling of loneliness became present. An unforgivable, agonising mystery that screamed from all sides.

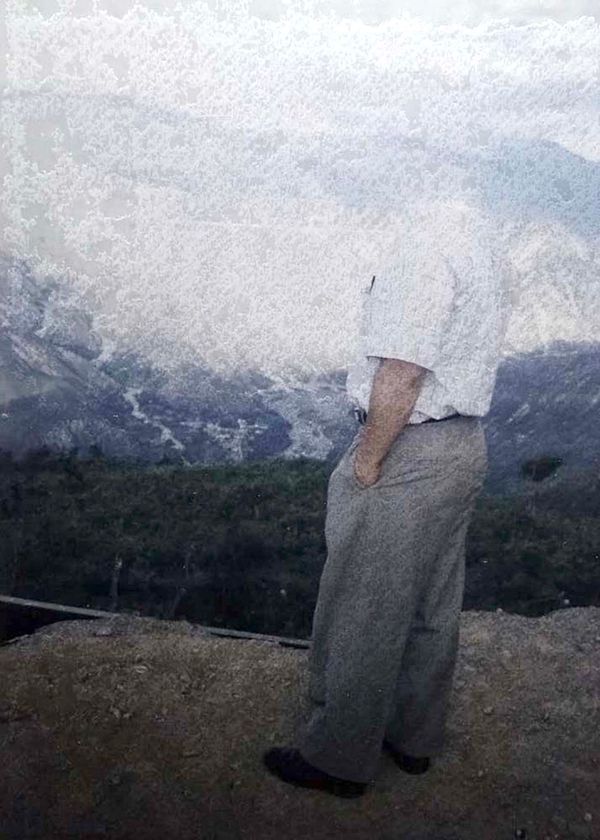

More than two years passed before I was able to approach this memory for the first time. It took long nights, an old camera, and the repetitive act of going to take pictures every night in the bushes surrounding the family house. I wanted to take photos of what I saw, take pictures of the house's ruins, capture the abandonment, the loneliness of being there. I started taking pictures to get closer to this story, to remember, open the memory and put it in front of the fire, to illuminate my memories to understand them. I soon realised that I could not recover a memory or understand this story alone. To do a project about our history, I needed to repair the family ties that the armed conflict had broken. I needed to ask questions, approach my family, interview them, and build a bridge.

It is an arduous task to have to repair to be able to see. It implies that this project is possible in the world of the affections and that the memory to which I appeal, the construction of truth and reparation, of a personal and family history, from which one can see Colombia, doesn't lie in the scientific world. The artistic strategies or my formal decisions regarding this project have been possible to the extent that I have managed to understand our stories and approach them honestly. Through empathy.

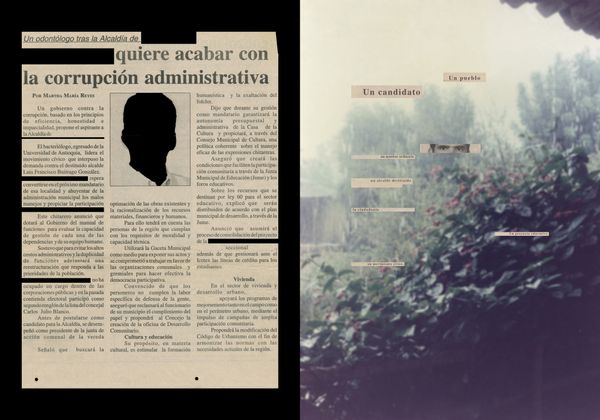

The event that triggered this project was my father's exile. In 2015 My papa crossed the Colombian border, fleeing the political persecution he had been subjected to for decades after finishing his term as mayor of a small town on the border with Venezuela. I remember him disappearing on different occasions when I was still a child, but then, fairy tales that my parents told me justified his absence. In 2015, for the first time, I understood my family was fragmented and separated in the harshness of a country where political violence reaches the worst statistics in the world. Arder la casa examines the multiple layers involved in the experience of exile and political violence in Colombia. Three elements run through the narrative construction of this project: fire, bullfighting, and the figure of the caudillo.

Fire is an element inserted in Colombian popular culture. Used in the December celebrations for the tradition of the Año Viejo: a doll in the shape of a person and natural size, stuffed with paper, is burned to symbolise the year's closing. Fire has also been used to threaten, frighten, instil fear, and in some cases, kill. Our house was set on fire in my family history as a threat when my father took office as mayor, burning part of the mountain of forest belonging to the property.

As a popular festivity in Colombia, bullfighting is practised mainly in villages of the Andean region; bullfighting symbolises the fight between two opposites that reflect each other. Bullfighting represents colonial culture, its inclination for the war, and the suppression of the other. Bullfighting symbolises an ideological and power struggle between two worlds and positions: that of the caudillo and the colonist.

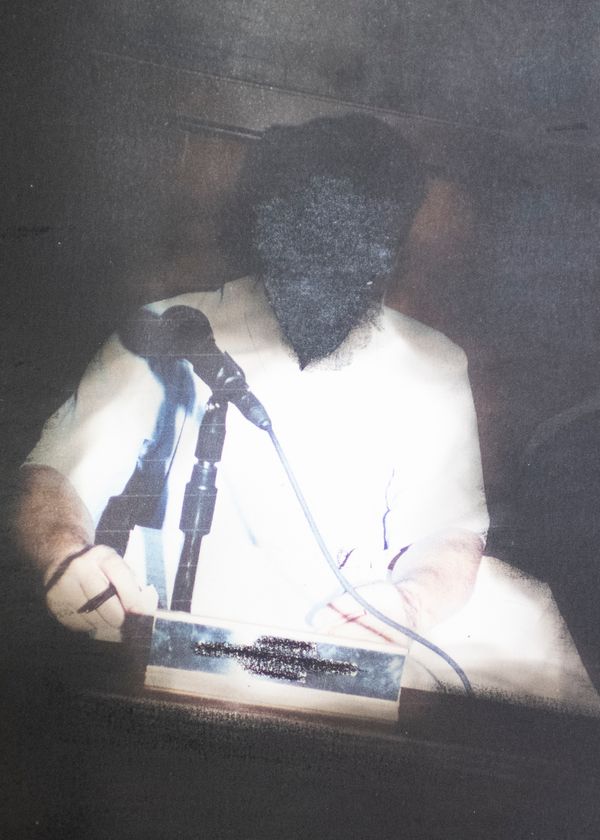

The figure of the caudillo is a historical, cultural, and ideological trope of an ordinary someone who saves us -the people- from the evils of the rulers. The caudillo is a romanticised figure that normalises state violence against social leaders and independent politicians—a heroic figure representing my father and the hundreds of assassinated and exiled in our state of war.

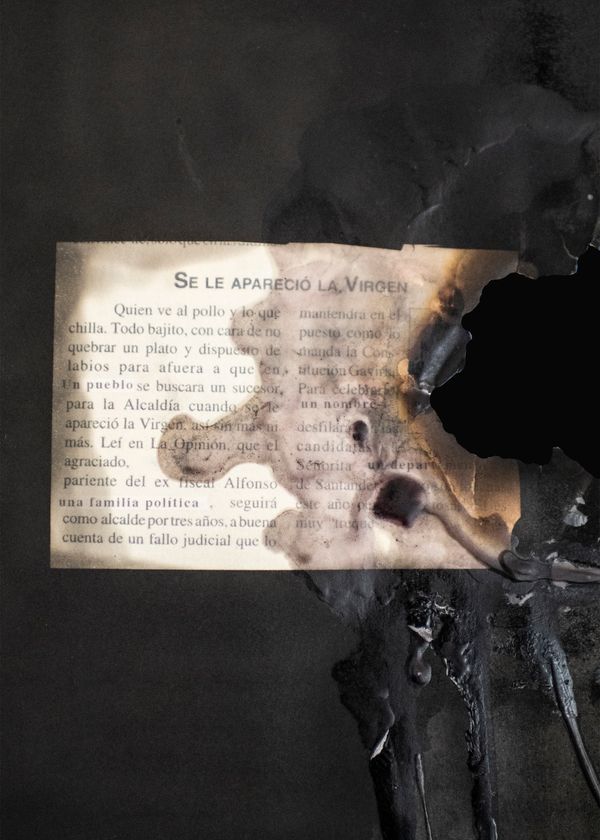

The use of archival imagery is the basis of the photographic work. I have recovered family pictures, newspaper clippings, letters, videos and objects and in the intention to reveal and protect our identities I have intervened the archive, using fire and dust, to cover the parts that can't be seen yet. The process of covering up resembles the strategy my parents used when I was a child by telling us stories that covered up the reality of war. It is a repetitive cycle, like an endless action in which every time something is covered, something is unveiled at the same time.

While walking through the images, pay attention to what is visible and whatnot, allow your senses to smell the smock, feel the fire burning each picture, hear the chants, inhabit the story.