Another Paris

-

Dates2022 - Ongoing

-

Author

- Location Uzbekistan, Uzbekistan

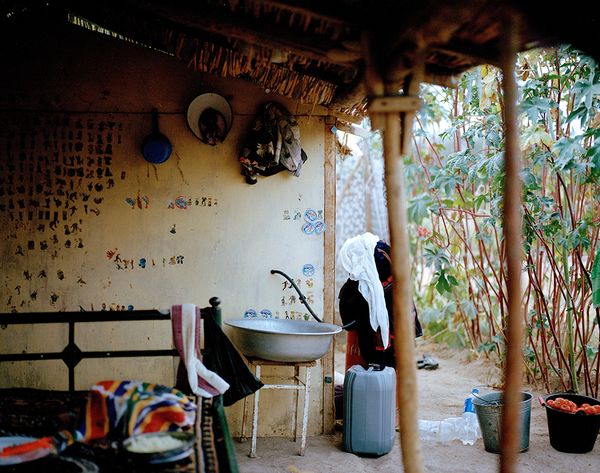

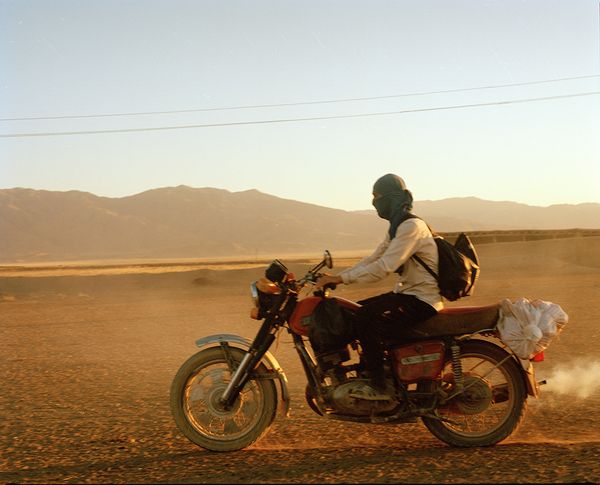

Another Paris explores a community of seasonal workers amidst Uzbekistan’s ever-globalizing economy and climate crisis. Set across airy, dusty, and dreamy fields of the Farish district, it shows my compatriots crafting their bond—strong, yet fragile.

For centuries, the people of nowadays Uzbekistan have been planting crops such as watermelons, melons, peanuts, tomatoes, and seeds. For decades, families of the Ferghana Valley in eastern Uzbekistan have been coming for months to the central part of the country as seasonal farmers, cultivating the rented fields from dusk to dawn and spending their nights in improvised temporary houses—chaylas built out of materials at hand. For three years, I have been visiting the Farish district and fostering my subtle connection with several such communities. Documenting stark realities of agricultural labor while getting to know the workers’ routine, plans, and communal joy, I explore a unique intersection of dreams and labor, summarized in the sight of an Eiffel Tower oddly placed at the entrance to a seemingly unremarkable village.

The tower’s replica in the Farish district is just one of many scattered across Uzbekistan. They all manifest the country’s fascination with Paris, both in big cities and remote villages. When my grandfather kept talking about his first years spent in the blooming Farish, as a child I used to think that he was so cool that he went to Paris—due to phonetic similarities. Now, a relative I refer to as uncle owns a set of fields in the district. Thus, these fields become rather a safe place for me as a woman to be there on my own—diving into the lives and stories of my uncle Alisher aka, who was briefing me on the economics of the fields, his wife Nasiba opa, who shared deeply personal stories of both happiness and grief, an adolescent couple, whose tender love sparked memories of my school romances, and many others.

Turning from digital photography to medium format proved key to fostering my connection with the farmers. Having to ask them permission to shoot, and then to stay still, do this or that while I am measuring the light and focus, I found their personalities becoming more present in the images. Juxtaposing the culture of shooting all dressed up spread across the country, and the embarrassment of appearing as one is in the pictures, I have been building the trust between us. Yet, I always try to preserve the mysteries they are hiding, and the sense of suspense tangible in our communications.

Another Paris series seems to me one of the many untold stories unfolding in Uzbekistan. Resisting both the glossy official imagery and Western orientalist misconceptions, I hope to capture our life in its great variety and warmth—and yet so fragile. Once, writing a diary entry at the end of a shooting day, I found myself questioning—how long will the farmers’ way of life keep on? As long as there is water here, I assumed then.