Anew

-

Dates2013 - Ongoing

-

Author

- Locations Lower Silesian Voivodeship, Wrocław, Poland, Wałbrzych

Long-term documentary on Lower Silesia – a territory that became a part of Poland after WW2 – and identities that formed there since.

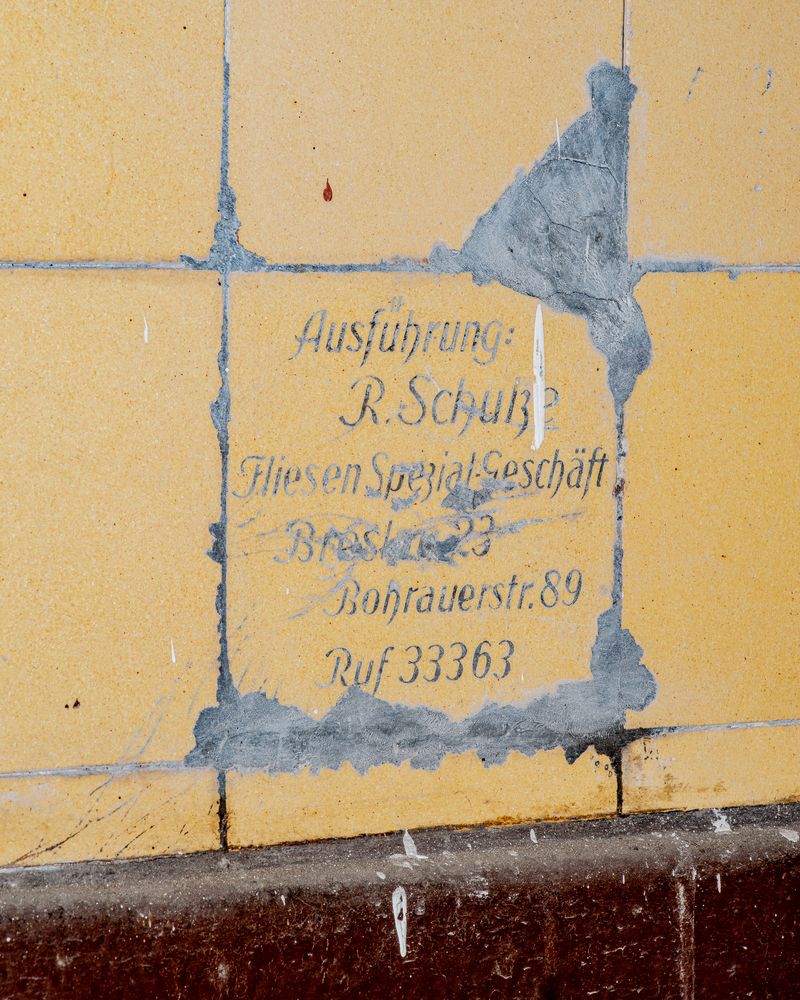

Anew is a long-term documentary project about the evolving identity of Lower Silesia—a region that became part of Poland after World War II but remains, in the public imagination, recognised as “ex-German.” As part of the so-called Recovered Territories, as they were called by the communist government, the region experienced both physical and symbolic erasure: streets were renamed, graveyards removed, and a millennium of German history overwritten by a state-sanctioned narrative of belonging.

Into this newly “blank” space came repatriates, displaced persons, and migrants: from former Polish eastern territories, Lemkos forcibly relocated during the Vistula Action, Greek civil war refugees, and re-emigrants from France. These communities found common ground in labor. Industry became the region’s backbone, supplying not only work but also housing, culture, and meaning. But after 1989, most of this infrastructure collapsed, leaving behind economic voids and fractured identities.

Today, Lower Silesia is a site of layered transformation: multicultural, post-industrial, and increasingly shaped by new waves of migration from Ukraine, Belarus, Korea, and beyond. Its capital, Wrocław –once a center of resistance and alternative culture – now stands as a symbol of these tensions and convergences. The Millennium Flood of 1997, when citizens came together to defend the city, is often cited by sociologists as the first moment a true Polish Lower Silesian identity began to take shape. What is it now? What is the sum of stories in the plural?

Anew draws on over a decade of fieldwork and archival research, combining photography and oral history. Structured as a non-linear narrative inspired by paragraph novels, it invites readers to assemble their own path through the region’s fragmented memoryscape. The project was awarded the 2024 Young Poland scholarship from the Polish Ministry of Culture and National Heritage, the President of Wrocław’s Artistic Grant, and the Pix.House Talent of the Year award in the Scholar category – all three supporting parts of the fieldwork, which is now completed. In 2025, Anew was also being presented as part of the Futures Photography platform.