Anatomy of Gaze (A)

-

Dates2024 - 2024

-

Author

- Topics Street Photography

- Locations Taipei City, Hsinchu City

At first glance, the book appears to be street photography—but it challenges how we see, reshaping reality and image through a critical exploration of the power held by both photographers and viewers.

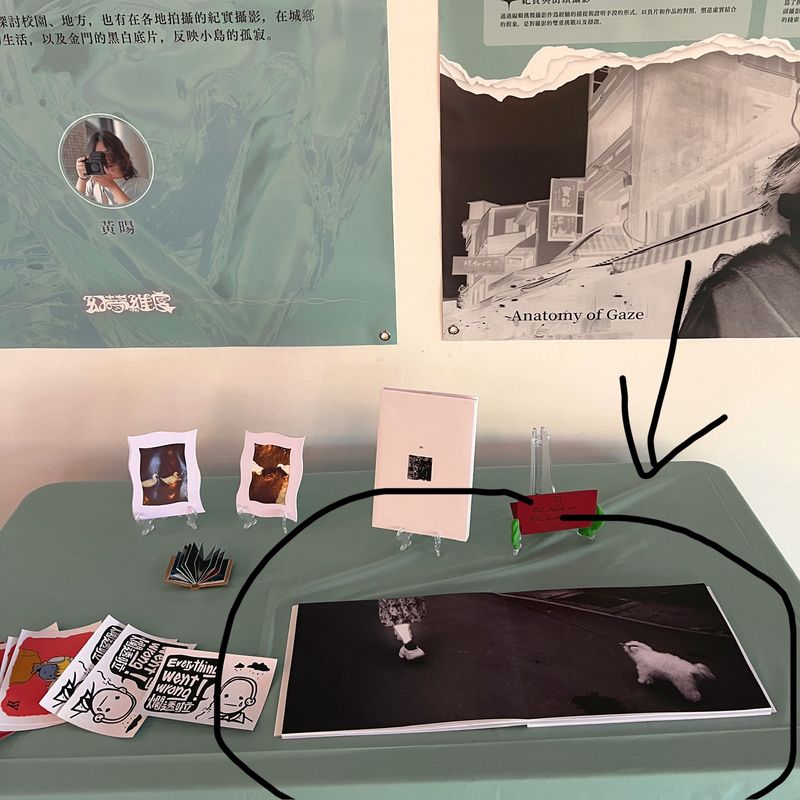

Anatomy of Gaze (A) and (B)

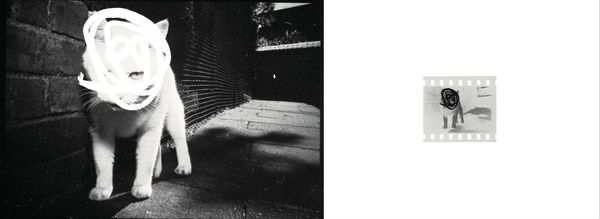

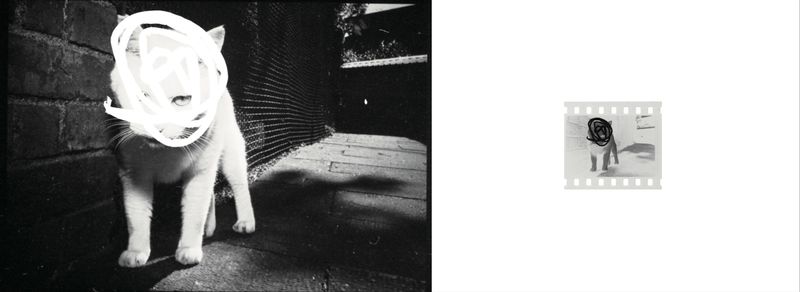

This time I submitted the book Anatomy of Gaze (A), it is the first book of this series, In (A) I primarily explored the boundaries of street photography, and the power dynamics within. In Anatomy of Gaze (A) I turned the camera to people I know, and people knowingly being taken photos of, and made collages with the photo taken, providing a different point of view rather than street photos.

Power Dynamics in Street Photography

In traditional perception, the photographer—by simply holding a camera—possesses a certain kind of power: the ability to define how the subject is portrayed, their status, and how they are presented. While street photographers may not operate with specific commercial or political agendas, they unconsciously take on the role of "agents of empire." Similar to how photography was used during colonial times to "collect" or "control" certain groups, places, and cultures—preserving images and defining a new world order—it disrupted the original texture of those cultures and became a tool for empires to write history and construct the image of the Other.

As Ariella Azoulay points out in her writings, photography carries an implicit violence: an image is not merely a visual record, but a kind of writing onto the subject, subtly shaping biases or stereotypes. Similarly, Susan Sontag, in her seminal work On Photography, asserts that the act of photography is itself a form of power—it can "Murder" a moment, or "Murder" a person, reducing them to a specimen inside a frame of film. These theories reveal an often-overlooked consciousness of domination embedded in the act of photographing.

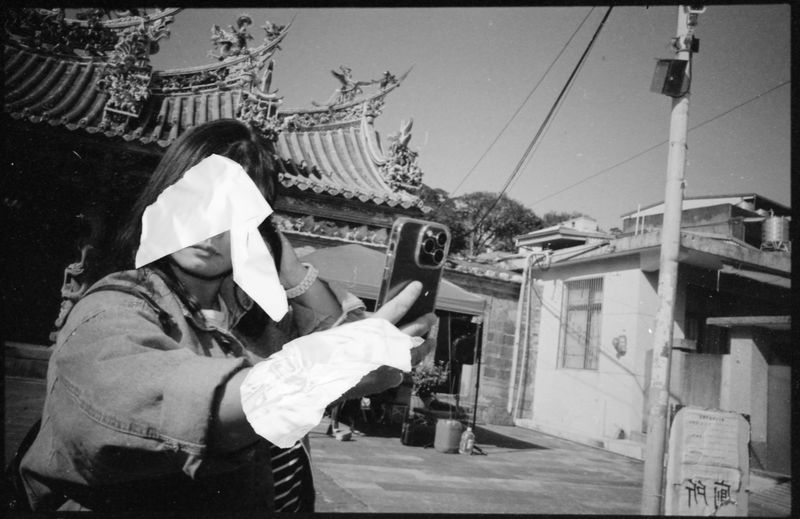

The Unconsented Gaze: Concept and Motivation

In Anatomy of Gaze, I work in everyday urban streets and public spaces in Taiwan, using analog film to capture the movement of crowds and ambient environments. Rather than relying on facial expressions or personal identity, I use techniques such as blurring, distortion, and glowing effects to erase individual identities. This challenges the dominant visual logic of traditional street photography, which often centers on the expressive face as a site of meaning or emotion. By removing the focus from the face, I shift the audience's attention toward spatial composition, gestures, and atmosphere, evoking a sense of both familiarity and estrangement.

Portrait Defocus and Reconstructed Identity: De-Identification and Viewer Reflection

Many viewers, when encountering a photograph, instinctively ask, “Who is this person?” or “What is their story?” Yet in Anatomy of Gaze (A), the facial features of the subjects are almost completely obscured. In Anatomy of Gaze (B), the faces are cut, collaged, and layered—evoking overlapping timelines and fractured identities. This approach to de-identification is not merely an aesthetic decision; it also represents a shift in power dynamics. On one hand, the photographer exercises the power to erase identity. On the other, it is a conscious refusal to let the subject become an object of curiosity or pity.

This treatment provokes critical questions in the viewer: “Do we really need to see a clear face to understand a person?” or “Have we simply grown accustomed to consuming and labeling people through their faces?” The blurred and glowing figures in the images force the audience to read the work through bodies, gestures, environments, and mood—breaking away from the conventional face-driven narrative of street photography.

Techniques and Visual Language

Glowing Skin: The brightness of the subject’s face is raised significantly above the background, dissolving facial features, skin texture, and markers of identity.

Negative-Positive Juxtaposition: Positive and negative images are displayed side by side to create a dialectical tension between "reality" and "fabrication."

Predominantly Black-and-White: A deliberate reference to and repurposing of traditional photographic language.

Film as Material: Process-Based Interventions

I developed my own negatives by hand, embedding the processing stage into the creative act itself. During post-production, I paint directly onto the negatives, introduce materials, physically distort the film, then scan or rephotograph and invert them. Faces are often blurred or treated with a soft glow—not as mere overexposure, but as an intentional visual treatment that floats between skin tone and artificial light. These “uncertain presences” are no longer recognizable individuals but become luminous forms that reflect light, color, and the act of looking itself. In some cases, they are partially obscured by objects or manipulated materials, further abstracting the body from legibility.

Authenticity in Question: Juxtaposing Positives and Negatives

I often present similar images in both their positive and negative forms within the same page. This gesture draws inspiration from the idea of the negative as “original evidence.” While a negative might appear to verify the truth of the positive image. This tension invites viewers to ask: “Is this real?” It destabilizes the assumed authenticity of photography, encouraging a more critical and reflective mode of viewing.