You Never Came Back: Serena Radicioli's Inquiry Into Loss and Memory

-

Published28 Oct 2025

-

Author

- Topics Awards, Contemporary Issues, Documentary

A candidate for PhEST Pop-Up Open Call 2025, Non sei più tornato (You Never Came Back) blends intimacy and investigation to reconstruct a fragmented, transformative narrative.

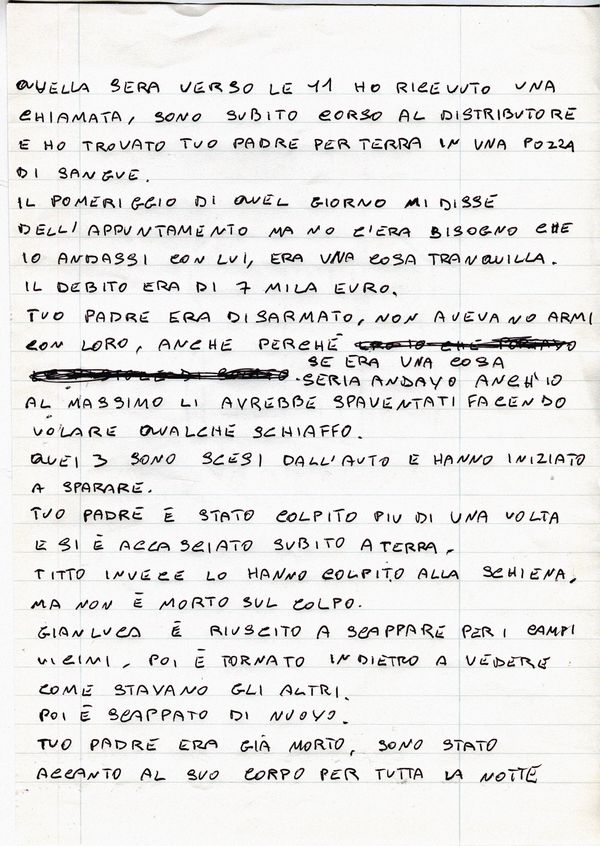

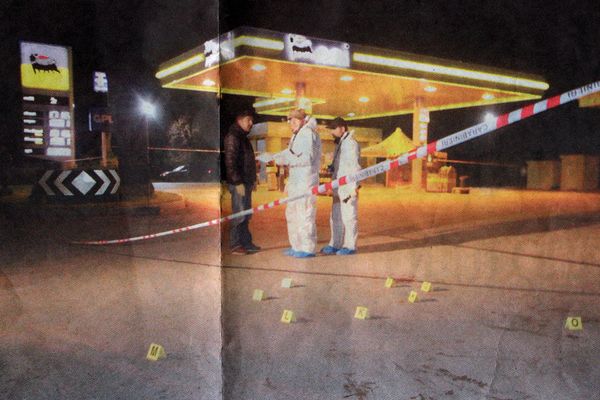

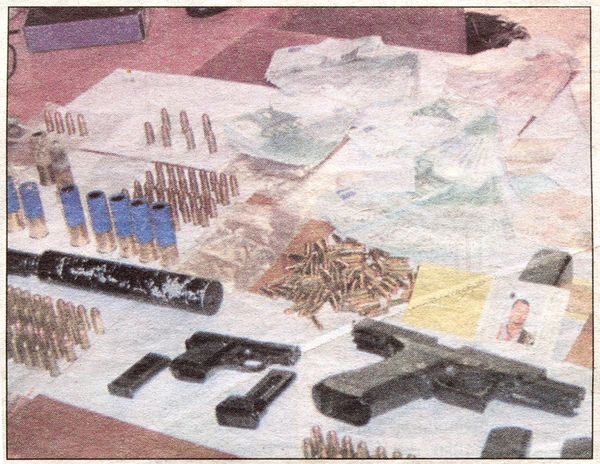

What are the inherent limits of representing the past, especially when that past is filled with ambiguity? The death of Serena Radicioli's father was sudden, and veiled in silence for years. Records and files, present-day photos, found letters, and direct testimonies are the pieces she has been bringing together since she started working on Non sei più tornato — a project that is about trying to reconstruct a complex story as much as it is about looking at photography as a critical tool for understanding and transformation.

As a result of PhEST Pop-Up Open Call 2025, launched for the 10th edition of the International Photography and Art Festival in Monopoli, Italy, we met up with Serena to delve deeper into her research. Learn more about her story, working methodology, and unanswered questions – and don't miss the opportunity to visit the exhibitions at PhEST, still open until 16 November.

Non sei più tornato is the outcome of a story that asked to be chased, an investigation you undertook in order to face a past that was never talked about. What was the catalyst that prompted you to begin this project? When and how did you recognize the moment when you felt ready to step into it?

The impulse to begin this project was born out of silence. The same silence that had always hovered around my father’s story, like a closed room everyone knew existed, but no one dared to open. For years, I avoided that threshold, until I realized that the emptiness behind it was slowly becoming part of me. Photography, for me, has always been a way of seeing what can’t be said. At some point, I felt the need to use the language I know best to give form to what had remained shapeless. There was never a precise moment when I “felt ready.” I simply understood that I never truly would be. Readiness came only through doing, through allowing myself to really look. Non sei più tornato was born this way: as an attempt to piece together absence, and at the same time, to make peace with it.

You wrote that this project taught you that photography cannot restore what is absent, but it can offer a space where absence becomes visible. What was the role of photographs – those you took, and those you found – in helping you understand and elaborate your father’s story?

The archival photographs I included in the project functioned as evidence: they confirm that those events truly happened, regardless of what I might say or believe. They are fragments of reality that resist interpretation, carrying truth across time. The photographs I made in the present, instead, were created to open a space where absence could become visible. Through the choice of details, framing, and light, I built a visual language to give presence to emotions, tensions, spaces, and silences to what has disappeared, and to what still exists yet feels distant. Together, these two kinds of images have formed a dialogue between memory, perception, and interpretation, allowing me to observe the past and transform it into something that could be processed and shared.

The images you use and create are reminiscent of both instant photography and the visual language of news and surveillance devices. How did your relationship with photography as a medium evolve while working on Non sei più tornato?

While working on Non sei più tornato, my relationship with photography evolved into a deeper awareness of both its power and its limits. I began to see it not only as a tool for recording or documenting, but as a medium capable of suspending time of creating tension between reality and memory, between presence and absence. The use of images that recall both instant photography and the visual language of surveillance allowed me to play with this ambiguity: photographs that appear objective, almost neutral, become at the same time intimate and revealing tools for exploring memory and perception. In this way, photography was not just a medium, but a counterpart: it forced me to look closely, to respect the emotional boundaries of what I was showing, and to search for a visual language capable of conveying sensations and tensions without the need to explain everything.

In this work you go back to seeing the story through the lens of a child, while confronting the past as an adult artist. How did these different identities merge within the narration?

Looking at the story through the eyes of a child allowed me to connect with the most immediate, instinctive, and often painful part of memory, while confronting it as an adult artist gave me the tools to observe, reflect, and give shape to that experience. These two identities coexist in a constant tension they shift between the vulnerability of the child who observes and the awareness of the artist who organizes and transforms. I also had to find an emotional distance from my own photographs, to allow that space to become something that could be shared. I never wanted to appear as a former victim taking pictures, but rather as an author with a complex and questionable past someone able to use personal experience as a tool for reflection and storytelling.

You bring together a wide range of images: empty spaces, isolated objects, portraits, family photos, letters and official documents. What was the biggest obstacle when integrating such various materials, public and private?

The greatest challenge was finding a balance between such different materials between what is intimate and personal, and what is public or documentary. Each element carries its own emotional and narrative register, and the risk was that the whole could become dissonant or confusing for the viewer. I had to work extensively on the selection and rhythm of the visual narrative, ensuring that each image or document could engage in dialogue with the others without losing its own autonomy becoming part of a complex yet coherent story.

From the side of a viewer, the project’s visual and narrative form requires active engagement, raising questions about the ambiguity of memory. While making this deeply personal work, were you thinking about the role the viewer might take in it?

For me, telling this story was both a way to analyze and to give something back. I didn’t want my experience to remain locked within its own singularity reduced to a private event or a personal wound. I wanted it to circulate, to find new voices, other bodies in which to resonate. I never felt the need to make it easy for the viewer to follow a straight path or to interpret the work without effort, because Non sei più tornato itself does not follow a clear line. I have always imagined the viewer as someone entering this space of memory and silence, ready to confront the absence and ambiguity within the story. The project was born as an act of openness a gesture of trust in the possibility that what was once silenced can finally be shared, and that those who look may, in turn, become part of this dialogue.

--------------

All images © Serena Radicioli

View the full project on PhMuseum

Serena Radicoli (b. 97) is a photographer and visual artist. She completed a two-year photography program at Officine Fotografiche (2018–2020) and earned a degree in Photography and Audiovisual Arts from RUFA – Rome University of Fine Arts in 2025. Her practice intersects documentary photography, archival exploration, and personal narratives, combining photographic work with found documents and family materials to visually articulate themes of memory, loss, and reconstruction.

--------------

PhEST is the international photography and art festival in Monopoli, Italy. PhEST is produced and promoted by the PhEST cultural association, with the support of the Puglia Region and the Municipality of Monopoli. PhEST was born in 2016 in Monopoli in Puglia from an idea of Giovanni Troilo, artistic director of the festival, and Arianna Rinaldo, who is in charge of the photographic curatorship. With the organizational direction of Cinzia Negherbon. PhEST is photography, cinema, music, art, contaminations from the Mediterranean. A way to give back their own voice to the thousand identities that make up the sea in the middle of the lands, redefining a new imaginary.