Peter Pflügler Discusses His Exhibition HANS At PhMuseum Lab

-

Published16 Dec 2025

-

Author

Hans - or - Don't Bury Me In The Grave Of My Father is a vulnerable, theatrical experience, exploring new ways to display a still-evolving body of work.

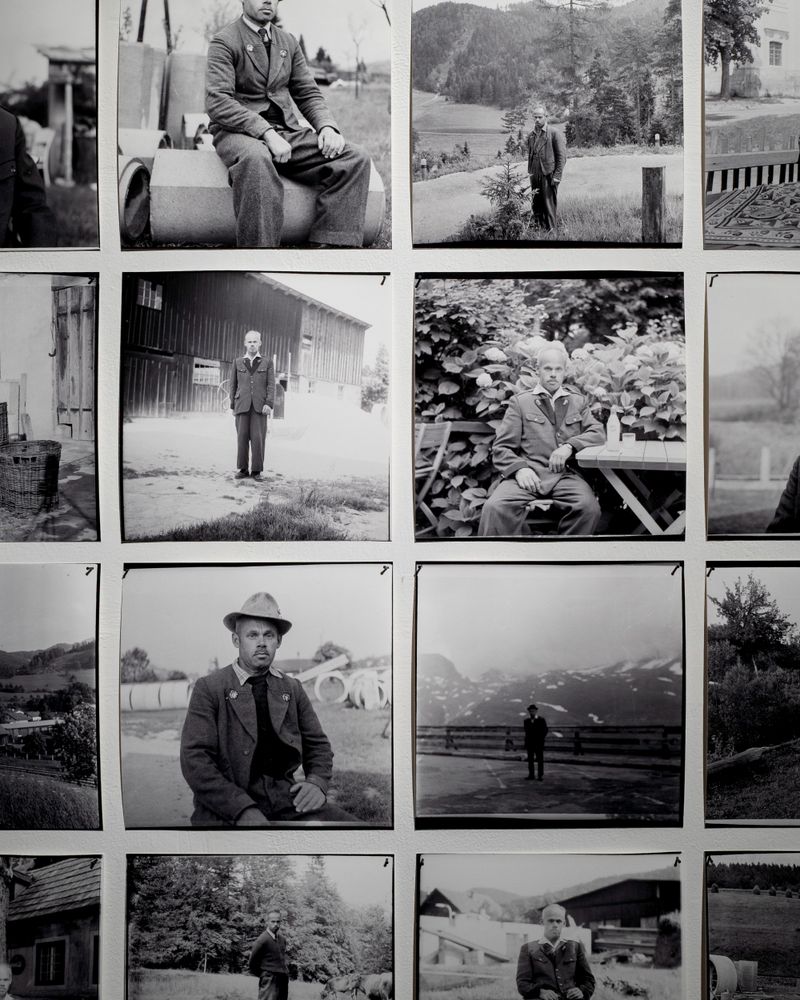

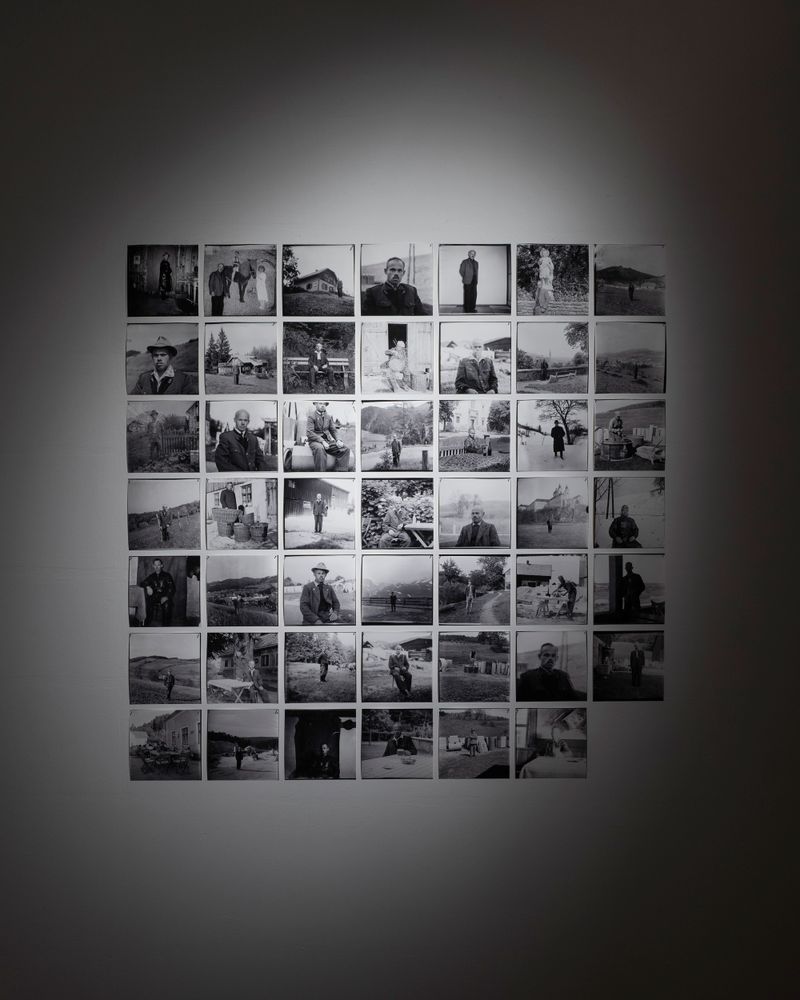

Developed during PhMuseum's 2024/25 CRITICAE Masterclass, Peter Pflügler's work starts with a found archive. Over a thousand negatives were left by Hans (1911–1997), the great-granduncle Peter never truly knew, who died at the age of 86 after an attempt at taking his own life. Between the 1940s and the 1990s, Hans photographed himself with relentless dedication. In response to his images, Peter takes new photographs and embarks on an almost investigative search: Who was this man? What are the reasons behind his last, unfulfilled wish – not to be buried in the grave of his father?

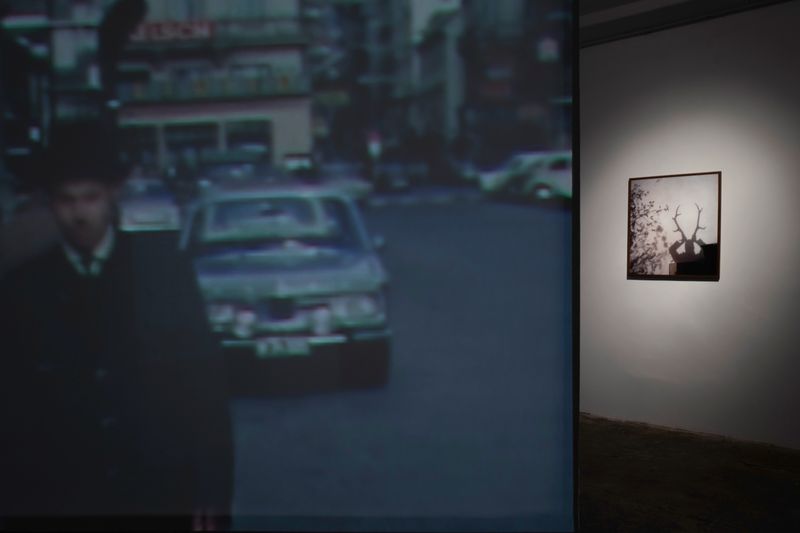

Designed as a three-channel video installation, the exhibition merges loss and celebration, theatricality and vulnerability. Photographs and videos appear and disappear across the screens, creating new encounters between the two authors. In the backroom, the space is turned into a studio, fully revealing the in-progress, evolving status of the project.

With the show still on display at PhMuseum Lab till 15 January 2026, we touched base with Peter to deepen in his evolving relationship with Hans, from its underlying photographic questions – how to photograph a ghost? – to a cathartic, disruptive ending.

Hans – or – Don’t Bury Me In The Grave Of My Father explores intergenerational trauma, mystery, secrecy and their lasting echoes – themes also present in your first photobook Now Is Not the Right Time. What was it like to revisit these subjects and approach them in a new project?

Those connections came as a surprise to me. After publishing Now Is Not The Right Time, I had a difficult time finding out what to do next. Having spent so much time with this deeply personal project, it was not easy to zoom out, and to find a new starting point. I was a bit lost and tried to be open to completely new things. When I started to dig into the archive of Hans, the connections to the themes of silence, secrecy and intergenerational connections slowly started to unfold. It was surprising and a bit scary. But I am happy about it, since it gave me a lot of curiosity and motivation to continue.

The work starts off from the discovery of Hans’ archive, counting more than a thousand negatives. What was it like for you to get to know him through his self-portraits, years after his passing? What did they allow you to understand about him as a person and a photographer?

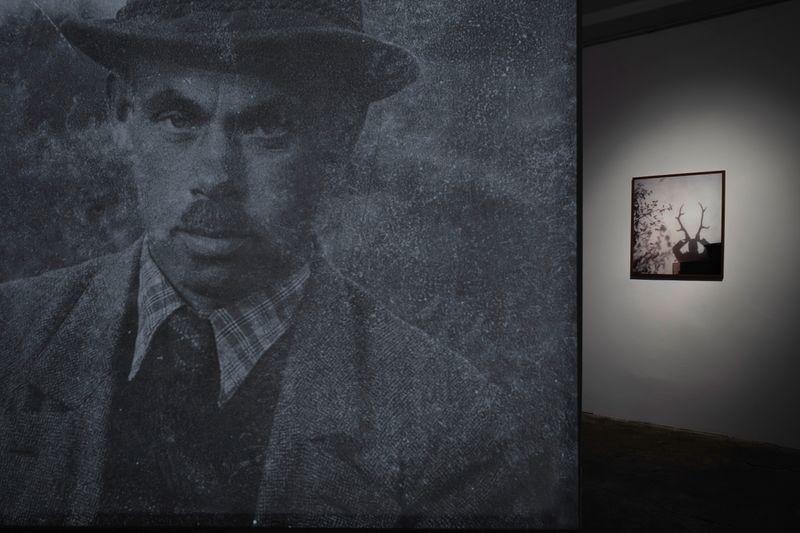

At the beginning, his self-portraits were an exciting mystery. I just could not understand why a man would photograph himself over five decades, without showing the images to anyone. What a dedication! And his gaze never changes. His expression is almost always the same, his posture is a bit strange, there is not one image without his moustache. Those images hold a darkness, something creepy. And at the same time, I felt this strong connection that I could not explain. I did not know much about him and his life, so I filled this gap with my assumptions and I started to investigate. The more I got to know, the more my feelings changed while looking at him. At the beginning, I was intrigued but scared, and later I simply wanted to take care of him.

Taking new pictures, you started a dialogue with Hans’ archive. What are the main artistic strategies you undertook in this phase? What type of relationship did you and Hans build throughout this process?

At the beginning my rule was: No self-portraits! I did not want to compete with his images, so I tried to photograph his clothes, or the places connected to him – his traces. It was difficult and frustrating, and slowly I realized that I actually wanted to photograph Hans himself. How to photograph a dead person, a ghost? My body and my shadow became tools to get closer to Hans. Whilst I found more and more connections between him and myself, I allowed my own persona and my personal story to become a part of the images as well. Hans wanted to end his life when he was 86 years old and I have reasons to believe that he was gay. I myself am a gay man, whose life was formed by the secret of my father's suicide attempt. There are all these connections. My family seems to have a long tradition of silence. I feel like my role as an artist and as a family member is to question this silence, even break it. I want to cautiously interfere and create a caring friction. I think Hans is helping me to do so, and I want to help him in turn.

With images projected on screens of 200 x 160 cm, the exhibition at PhMuseum Lab plays with the theatricality of your and Hans’s work. Are staging and performance a meeting ground between you two?

In my last project Now Is Not The Right Time I developed a working method, where I use existing scenery and then interfere by staging certain components. It is through this staging that I get closer to the essence of what I want to tell. But I am not a world builder, I am a world transformer. I want to use the backdrop of the banal and then scratch a hole in it. I think that Hans was also working in a similar way. He staged himself in all these frames, he is the hole in the banal.

The three-channel installation creates an ongoing exchange between his archive and your photography. Images appear and disappear in ever-changing, simultaneous configurations. How did this format shape the narrative flow of the project?

I was very happy with this presentation idea by the curatorial team of PhMuseum. It creates a timelessness and a theatrical experience. The audience can look at one screen, at one image at a time. Or they stand further away, looking at a diptych or triptych. At the same time, generations are intertwined and shuffled. Wonderful!

You have decided to fulfill Hans’ last wish – not to be buried in his father’s grave. By unearthing his body and granting him the burial he deserved, you will give this story a different ending. What are your thoughts on agency and justice, and how do you think photography can be at play in these concepts?

Hans was abused by his father. His last wish was not to be buried with him and yet, they still share a grave for almost 30 years. This is not fair. It is not right. During the project, I realized that in a way I am living the life that Hans was hindered to live. I believe in the shadows of our ancestors as well as in the responsibility of the living. I owe it to him, and it feels cathartic to finally grant his last wish. I am aware that it is a disruptive plan. Once in a grave, you normally stay there and there is something daring in disturbing the silence of a graveyard. I am also not doing this solely for Hans or for myself, I believe that this can have an impact on my family, our village and of course the audience of the project. Honestly, I am not sure if photography has a special role in this. Like every art form, it has strengths and limitations and whilst I think it can be valuable and also fun to think about them, I am not very busy with these questions during my practice. If I would be a writer or a filmmaker, my agency and thrive for justice would be the same.

The work is still in-progress and the exhibition embraced such status. What was it like for you to exhibit an unfinished work?

It was a valuable experience to share something “unfinished”, to be vulnerable and to be observative. I am happy that I could be present at the opening, to watch people look at the work and interact. It's great to see what works well and which parts are maybe not clear enough yet. And honestly, it is also simply a wonderful feeling to see the potential of the project and that I am in the middle of something substantial.

You developed this project during the 2024/25 edition of CRITICAE, PhMuseum’s Online Masterclass on Documentary Photography led by Elisa Medde and Laura El-Tantawy. How did this context support the development of the work and which moments were pivotal in shaping it?

There are several things that I am very thankful for, regarding my experience during CRITICAE. Having a structure of feedback, being able to share processes and being in a safe space to experiment and question. Creating a project can be a lonely place, it was great to have a community and the caring guidance of Elisa and Laura. Thank you!

What are the next steps for you and Hans?

There is a lot to do still! I haven't finished scanning all the negatives of the archive. I am continuing to photograph and I am writing a lot of text. All this material will find its place in a book publication. But above all that, I am getting you out of this grave, Hans!

----------

All images © PhMuseum

----------

Hans – or – Don’t Bury Me In The Grave Of My Father is on show at PhMuseum Lab, Via Paolo Fabbri 10/2a, Bologna, Italy, from 28 November 2025 to 15 January 2026.

Vernissage: 28 November 2025, 6.00pm - 9.00pm

Opening Days: 11 December, 18 December and 15 January, 5pm - 7pm. Other dates on appointment only.

----------

Peter Pflügler is a visual storyteller from Austria, living in the Netherlands. He studied photography at the Royal Academy of Art, The Hague. His work is about the impossibility of secrets and the transformative power of silence. He believes that what is hidden and unspoken influences our lives. By using staged photography and text, he carefully tries to uncover and rewrite personal stories.

----------

The PhMuseum Online Masterclasses aim to help participants advance their expertise and establish a solid, long-lasting creative practice. Each course is tailored to meet the needs of emerging photographers, artists, curators, and contemporary storytellers looking to bring their methods to the next level. Check out which program suits you best at phmuseum.com/education