Photobook Review: Yoko by Masahisa Fukase

-

Published22 Jul 2025

-

Author

- Topics Photobooks

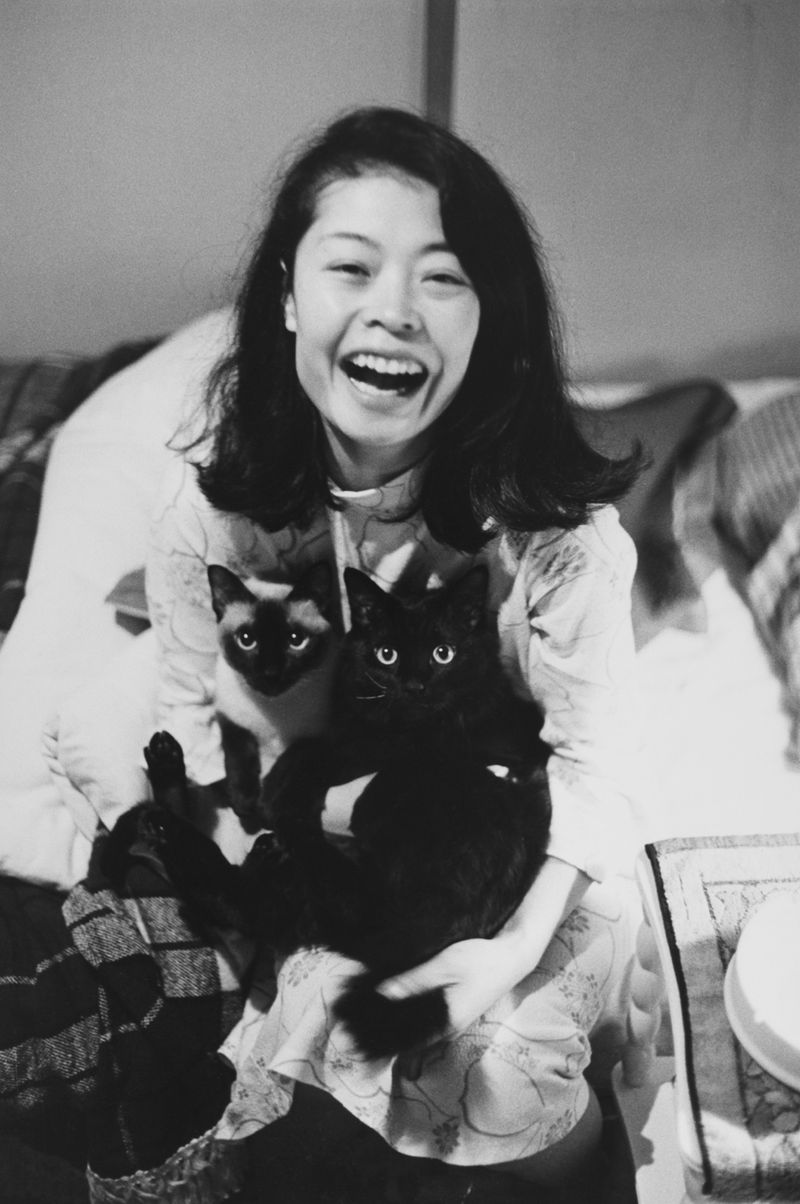

Yoko is a book about Yoko Miyoshi, the former wife of Masahisa Fukase. When they were married he photographed her endlessy; at home, on the street, with family, and finally after she divorced him, through the images of ravens he made in his sorrow.

Yoko is a book about the places in photography where obsession, coercion, performance, and self all combine.

Accompanied by texts from Yoko herself, the book reveals something of both the limitations and the opportunities that non-stop photography of the domestic and familiar can bring. It’s also a book about the pressure valve of photography, the strain of constantly being under the camera’s gaze, and the resentment that can bring.

“Day after day, all he thought about was photography,” she says in one extract from a 1973 edition of Camera Mainichi. “He was the only one in the world with passion, the only one living, the only one struggling with his thoughts…. In the ten years or so he lived with me, he only ever really looked at me through the camera lens and it seems to me that those pictures of me were obviously only of himself.”

Though it’s common in photography for people to problematise images that have been made about them, in the distant world of photojournalism in particular, it's less common for people intimately connected to a project to bring up their doubts about the authenticity of the images made. That’s what Yoko does here.

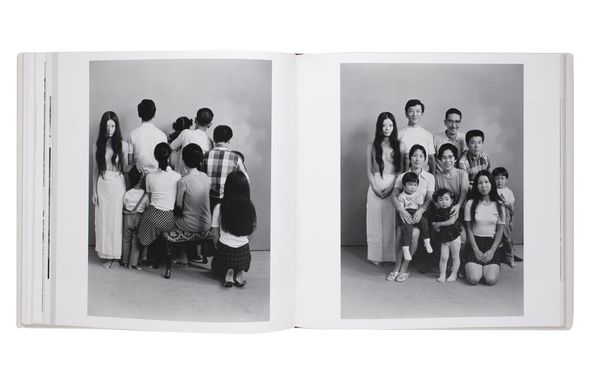

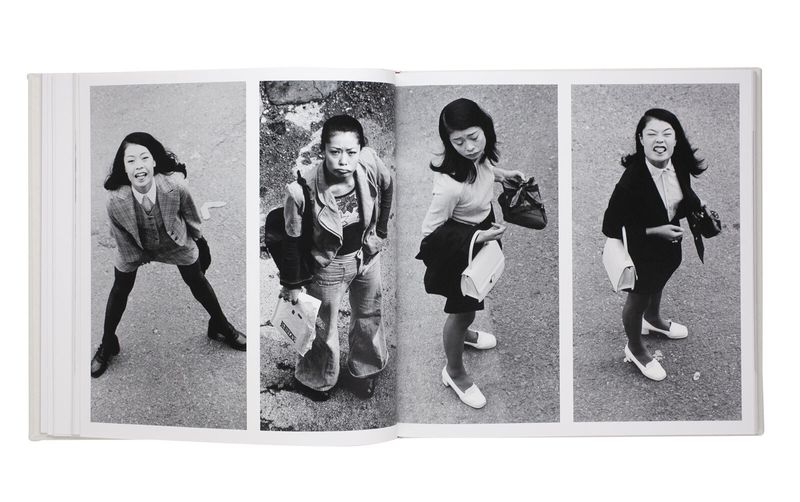

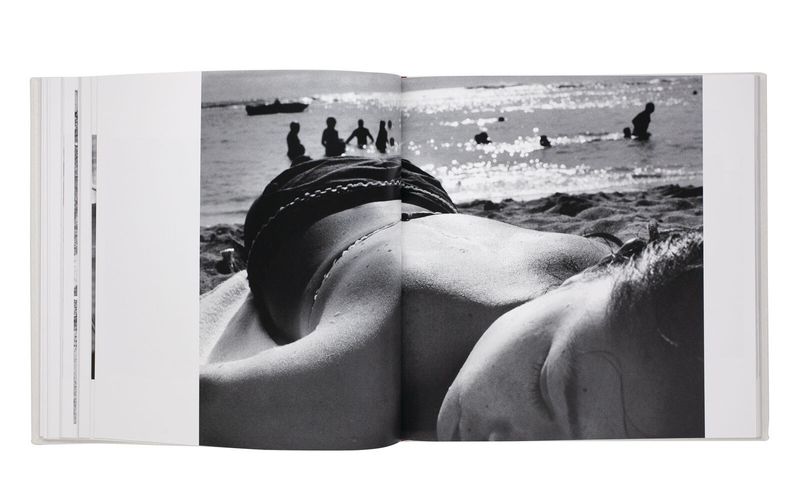

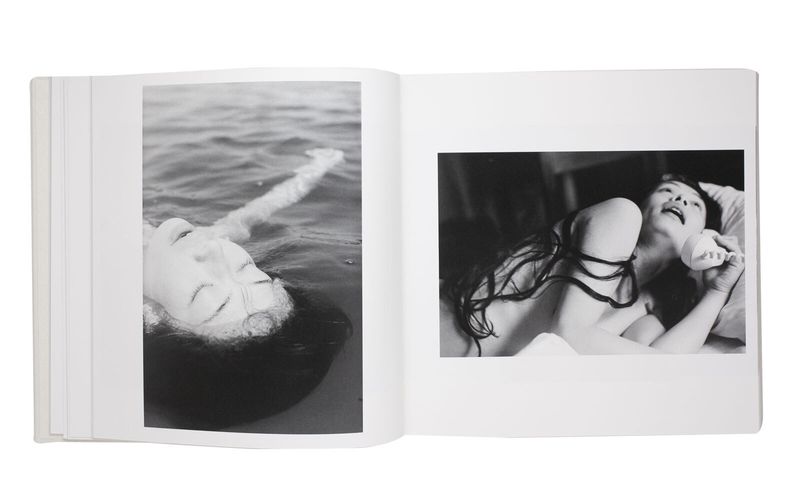

There are images of Yoko from Fukase’s well-known family series, there's Yoko on the street, old ladies and raggedy street scenes in the background, she lies naked on the bed, a crab protecting her modesty, and there’s Yoko photographed on the street from the apartment window above, part of Fukase’s best known project on his wife.

The pressure to perform for her husband’s photographic rituals is evident in the book. It’s a side element to the book, but a fascinating one that adds a huge amount to the images, fabulous as they may be. This pressure is evident in everyone who makes photographs of their family. Like washing the dishes or taking out the rubbish, photography can be a pitiless chore, and Yoko reveals something of the futility of forcing the photographic issue, something that is equally evident in every photo festival, gallery, or book shop you have ever attended.

“Recently, I only go out two or three times a week,” writes Yoko from the distant land of 1973, “but he insists on driving me out of the apartment. I don't have a choice, so I put on makeup and go outside into the rainy season weather dressed to go out. For more than 10 days now I've waved my hand, raised my leg and smiled brightly for the telephoto lens on the 4th floor. The photos he chose all made me look like a monkey, or like I had polio, or like a mean old lady. To top it all off, he lightly declared, “Still last year's photos are better. These faked photos just don't work.” Despite pressuring me for nearly half a month to do something I really didn't like doing, exposed to the curious stares of passers-by, he refuses to take any responsibility for it.”

Here, Yoko is expressing a simple point on authenticity, on performance, on the split between being, acting, posing, and the photographic cliches they overlap with. And this is coming from somebody who can pose, perform, and act wonderfully.

Again, it’s an interesting thought that some people do perform better for the camera, do shine somewhat more brightly or darkly once you stick a camera lens in front of them. A lot of people really do not, and a lot of photographers, as in all of us, at times resort to blank-stared looking into space or out of windows strategies to impose some kind of inner space into the picture.

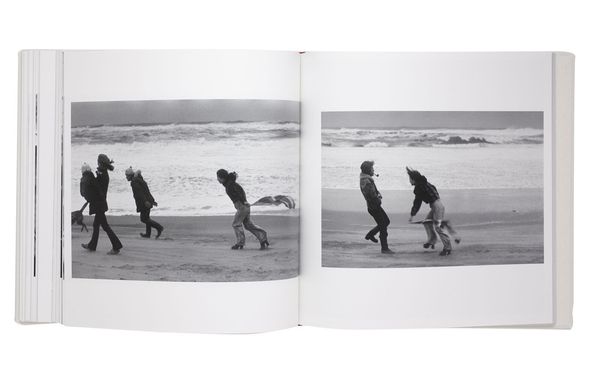

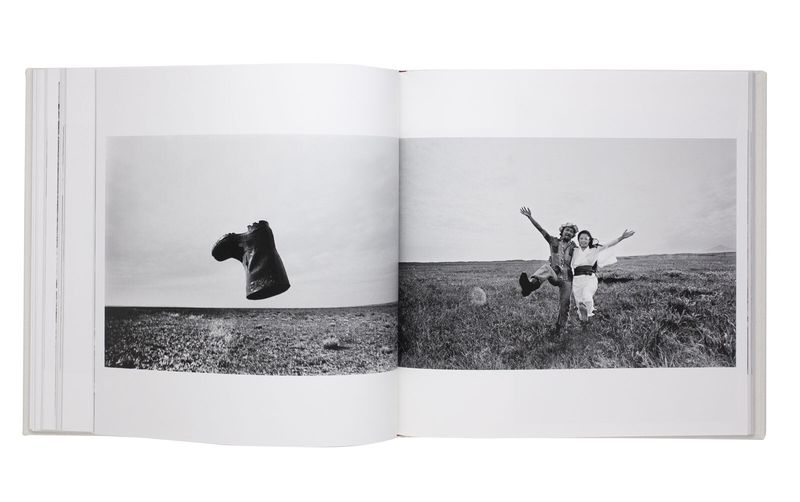

That, let it be said, is not Yoko. There are times when the freedom of her spirit launches her beyond the camera; from the wedding picture where she gives a sideways glance as the couple’s families pose solidly in the background, as she runs topless across a field, her long black hair streaming behind her, her mouth spread wide into an anime smile, or when she stretches her arms out on a broad pavement, her shadow reaching out into the foreground.

At other times, she is more subdued, as in the formal portrait where she attempts and fails to smile. We see two versions of it, one of which is behind smashed glass, an accidental homage perhaps to the great cover image of Kiyoshi Koishi's 1933 classic Early Summer Nerves.

There are also some words from Fukase. “From the day I was born I have grown up entirely in the world of photographs,” he writes in a 1975 edition of Camera Mainichi. “That can’t be undone but I've always gotten the people I love tangled up in my world on the pretext of taking pictures. I could never make anyone happy, including myself. I keep going astray and I've led others astray too. Is the joy of photography worth the sacrifice?”

Yoko possibly thinks not. As a life partner, she dismisses him as “a hopeless egoist,” who puts the camera before everything, herself included.

She said that the pictures he made of her “are obviously pictures of himself.”

That may be true, but as you go through the book, there are some pictures taken from Ravens, his great book on his loss of Yoko. And perhaps it’s here that the real Yoko and the real Fukase come together in the photographic image of these avian portents of doom stretching their wings out, alive or dead, in the air, on the ground, or frozen in the snow.

But perhaps not. A raven is a raven after all. It is what it is. And it is not what it is not.

--------------

Yoko by Masahisa Fukase is published by Akaaka Art Publishing

Book Size 245 × 245 mm

Pages168 pages

Binding Hardcover

Publication Year2025

Language English, Japanese

ISBN978-4-86541-196-6

--------------

All images © Masahisa Fukase

--------------

Masahisa Fukase (Hokkaido, 1934 – 2012) is considered one of the most radical and experimental photographers of the post-war generation in Japan. He would become world-renowned for his photographic series and subsequent publication Karasu (The English title: Ravens, 1975 – 1985), which is widely celebrated as a photographic masterpiece. And yet the larger part of his oeuvre remained largely inaccessible for over two decades. In 1992 a tragic fall had left the artist with permanent brain damage, and it was only after his death in 2012 that the archives were gradually disclosed. Since then a wealth of material has surfaced that had never been shown before.

Colin Pantall is a photographer, writer and lecturer based in Bath, England. His next online courses and in person workshops in Bath and Sicily begin in October 2025. More information here. Follow him on Instagram