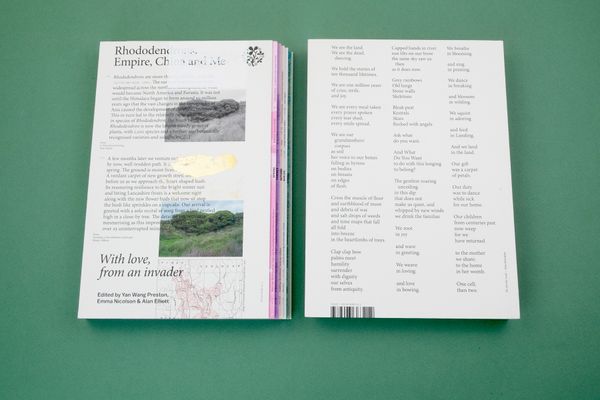

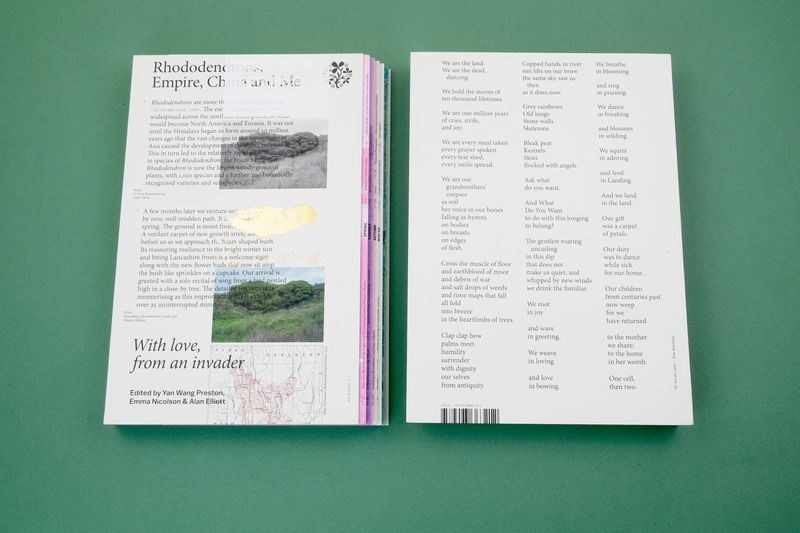

Photobook Review: With Love. From An Invader – Rhododendrons, Empire, China And Me by Yan Wang Preston

-

Published23 Sep 2025

-

Author

With Love From An Invader tells the story of rhododendron ponticum. Native to Southwest China and the Mediterranean, it’s a species of plant which contains multi-layered histories; of colonialism, landscape, and ideas of migration, invasion and belonging.

It’s a multi-layered book for a multi-layered subject, the terraced, titled fore edge reflects this. It contains a year-long series of Wang Preston’s images of a particular rhododendron bush, it features archive material looking at the history of rhododendron extraction in China, and it looks at what constitutes landscape, what makes a native species, where do names come from (and what are the names that have been forgotten or erased), and what constitutes an ‘invasive species’ in both botanical and human forms, in particular in relation to Preston’s personal history..

The rhododendron is a much maligned plant. Under the Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981, they are a Schedule 9 species. They are toxic and little can survive in their shade and so join Japanese knotweed, Himalayan Balsam, the Italian Crested Newt, the Canada Goose, the Turkish Crayfish, and the Chinese Mitten Crab as one of many migrant species unwelcome on Britain’s pristine shores.

At the same time, the rhododendron is a plant that was brought to the UK. It was uprooted from its Himalayan (and Iberian) homes and planted, fed, and watered in the stately homes of Britain. Go to the driveways of Longleat, the gardens of Stourhead, or the arboretum of Westonbirt and you will find them growing in all their glory.

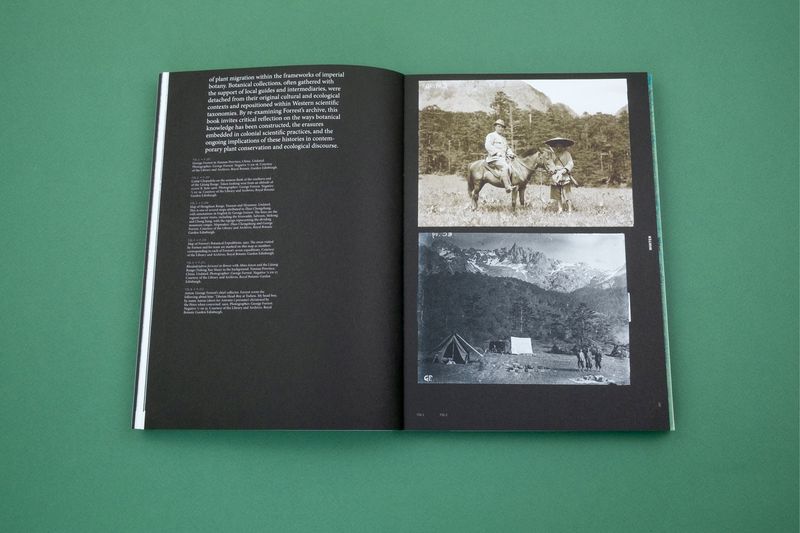

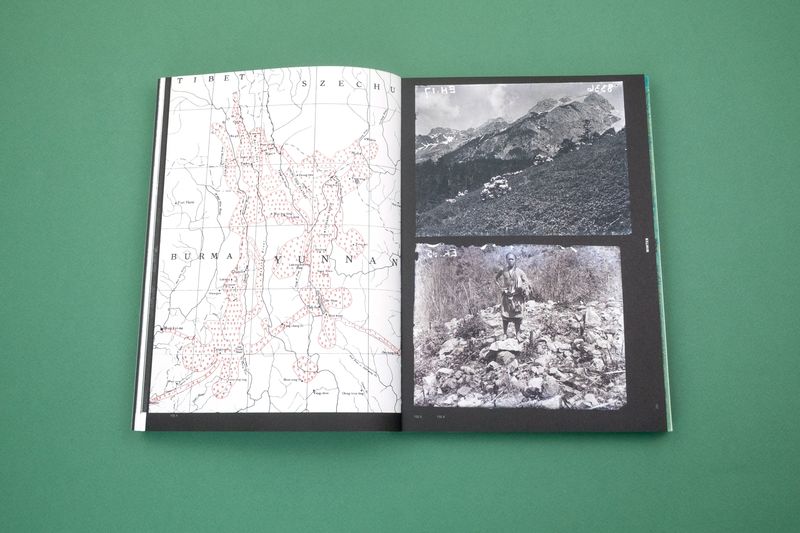

How they came to the UK is detailed in the final part of the book, where we see archive images from the Royal Botanical Gardens in Edinburgh. These show the botanist George Forrest (the ‘Indiana Jones’ of Botany) collecting specimens in Yunnan Province in China.

What was lost when Forrest brought the plants to Scotland was the local heritage embedded within the plants. The rhododendron was part of the cosmological worldview of the local Naxi minority group. Rhododendron trees guarded the entrance to the realm of the dead and their leaves were used for spiritual cleansing rituals. Their name for the plant was also erased as it was renamed using European languages according to the Linnaean worldview.

This erasure is at the heart of multiple academic, botanical, and artistic studies of plants that seek to recover indigenous and minority knowledge and naming as well as re-evaluating the destructive practices brought by botanist-explorers and others. These practices extend into more recent history; during the Cultural Revolution of the 1960s, Red Guards destroyed extensive rhododendron plants for the role they played in Naxi religion, part of an epidemic of destruction that sought to eliminate old ways of thinking, being, and living, especially those of minority peoples such as the Naxi or Tibetans.

That destructiveness, that erasure, is what this book is about. It emerges from a personal connection. Like the rhododendron, Wang Preston is a migrant. She came to the UK from Beijing at the age of 20, finding herself in an unfamiliar land, but she became part of the territory, becoming British in the process.

That is another part of the book; it looks at the contingency of ideas of nativeness and invasive species. It comes through Wang Preston’s photography, in which she pays homage to some of China’s great contemporary photographers. One of the numerous essays that are threaded throughout the book details the connection between geology and the rhododendron. It identifies fossil sources of the plant in Ireland and asks if the rhododendron would be native had the ice age not existed. And it questions whether, with climate change, there wouldn’t be a shift in rhododendron habitat from the Iberian Peninsula to the shores of Britain.

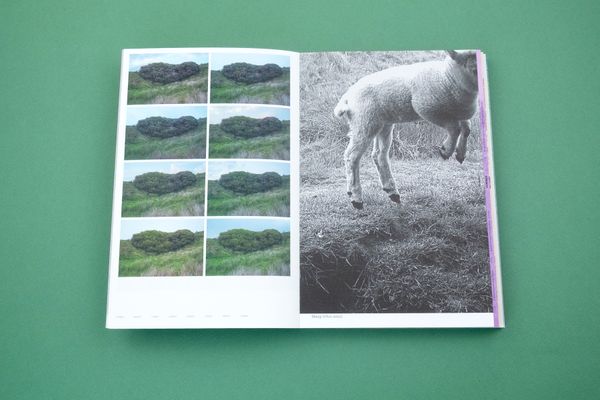

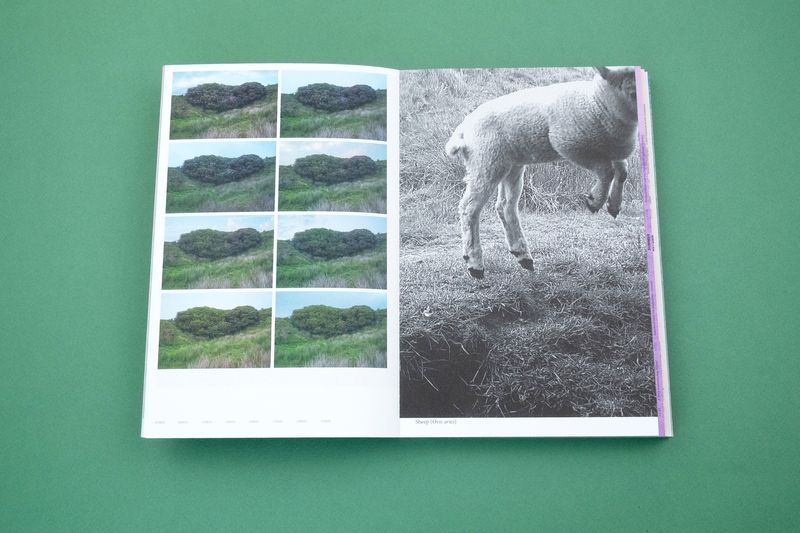

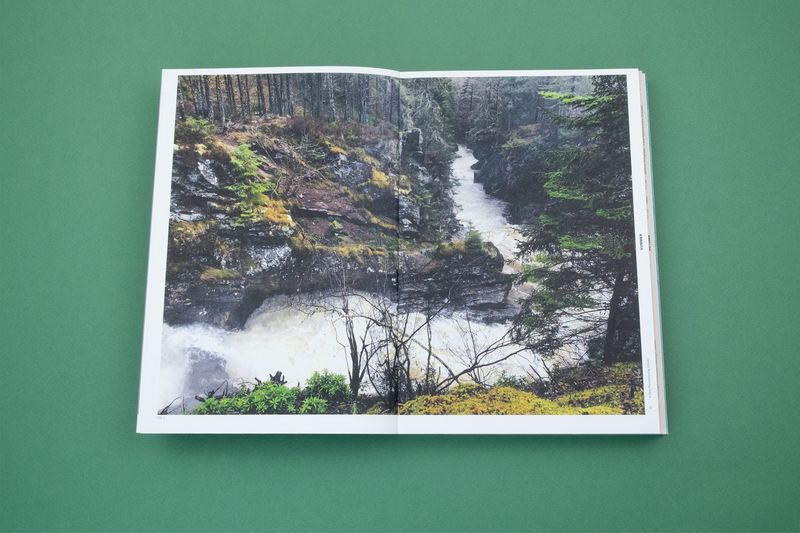

What ultimately is the natural habitat for flora and fauna is the heart of the question here. Wang Preston seeks to answer this visually through her yearlong engagement with a heart-shaped rhododendron on Shedden Clough in Lancashire.

Shedden Clough is a former industrial site from which lime was extracted. It’s a marginal landscape that Wang Preston becomes part of. She photographs her heart-shaped shrub every other day for a year, these images becoming part of her spring, summer, autumn, and winter sequence. She collects the leaves, aborted buds, seed capsules, and fading flowers, pulls them apart, and photographs them in contemporary botanical fashion. She photographs the landscape from her drone, includes trailcam images of the landscape, and (we learn from an interview) makes sound recordings.

It's a rough-hewn landscape, and we read an interview from an owner who has opened it up to access, adding another string to the landscape bow. The rhododendrons may have been planted to provide cover for pheasants and other game birds. Like so much land in Britain, this was land for hunting; wasted land, exploited land, land that comes at the expense of others, land that excludes others, land that, through ownership, erases its own history as land that belongs to nobody.

But land ownership in Britain (and in England especially) has its own mythology, its own romance, one that so many of us cling to (the appeal of movies and TV shows like Downton Abbey is founded on this), no matter how destructive or unrepresentative it is.

That romanticisation is evident in another strand of the book: the postcards. Taken from the collection of the Edinburgh Royal Botanical Gardens, they show an exoticised vision of rhododendron in bloom at Glencoe, Cragside, and Argyll.

It’s a representation that is in some ways at odds with the demonisation of rhododendron as an invasive species, but like all exoticisations, it has at its heart a misrepresentation. And that is what Wang Preston does in this book. She asks questions of the representation of non-native fauna and, by extension, asks the question of herself.

What does it mean to be native and when do you measure it from? In Britain, who counts as native and who counts as an invader, and more to the point, who is doing the counting and when does the counting start?

At the end of the book, Wang Preston writes about her photography being ‘embodied photography’; photography that could potentially reveal ‘the optical unconscious… rather than media for documenting.’

This revealing extends to who she is and what the rhododendrons are. The process of making the work, she writes, ‘… became a journey of self-discovery, where one woman’s story was intertwined with stories of the migrating rhododendrons.’ These rhododendrons have ‘…stories of resilience, of putting down roots whenever possible, of making homes for themselves and others wherever suitable. They help me to reconsider the ‘non-native invasive’ plants simply as ‘plants that arrive.’

--------------

Author: Yan Wang Preston

Dimensions: 170 × 240 mm | 320p

Binding: EN | Softcover

Release date: Summer 2025

First edition: 900

ISBN: 978-94-93363-21-2

Retail price: €35

--------------

All images © Yan Wang Preston

--------------

Yan Wang Preston is a Chinese British visual artist interested in landscape representation, identity, migration, and the environment. Her other projects include Mother River (Berlin: Hatje Cantz, 2018), Forest (Berlin: Hatje Cantz, 2018), and Three Easier Pieces (2021-ongoing).

Colin Pantall is a photographer, writer and lecturer based in Bath, England. His next online courses and in person workshops begin in October 2025. More information here. Follow him on Instagram.