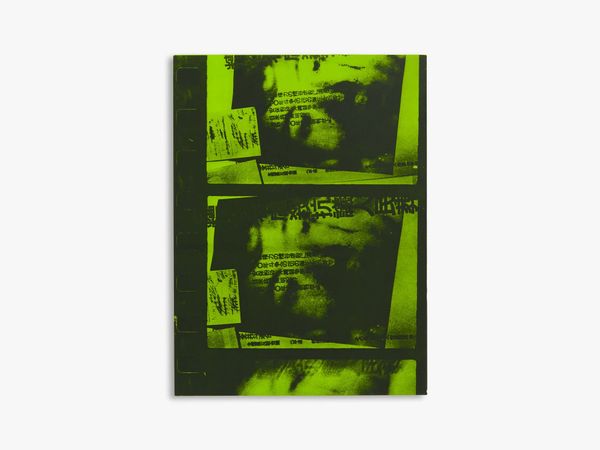

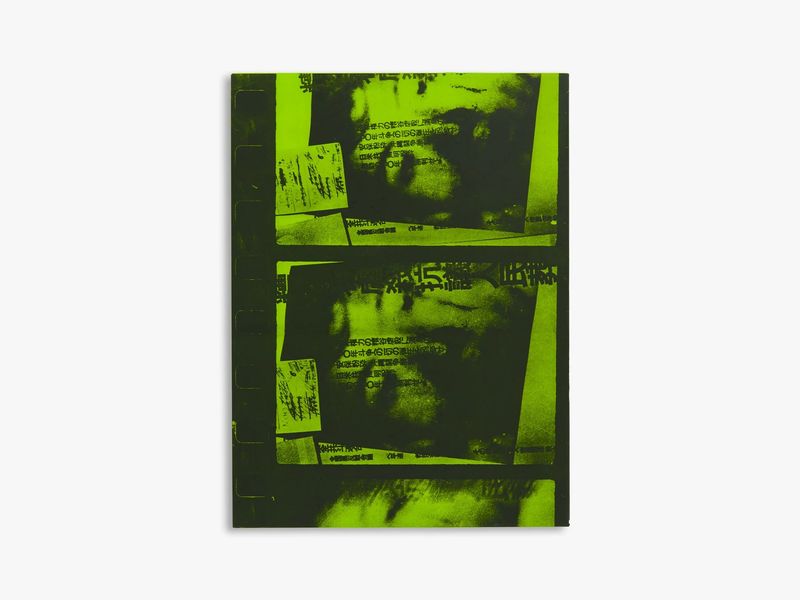

Photobook Review: Quartet by Daido Moriyama

-

Published24 Nov 2025

-

Author

Quartet is a collection of the images from Daido Moriyama’s early photobooks. It details the time when Moriyama was photographing Japan through its economics, politics, and culture, together with the cynicism he felt for photography.

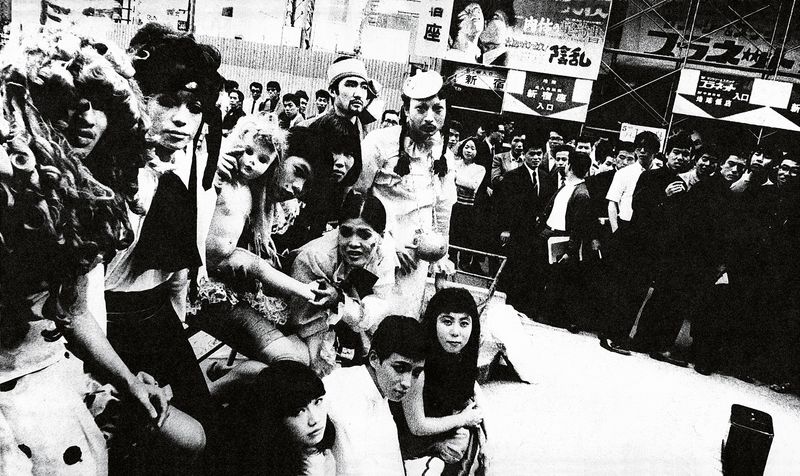

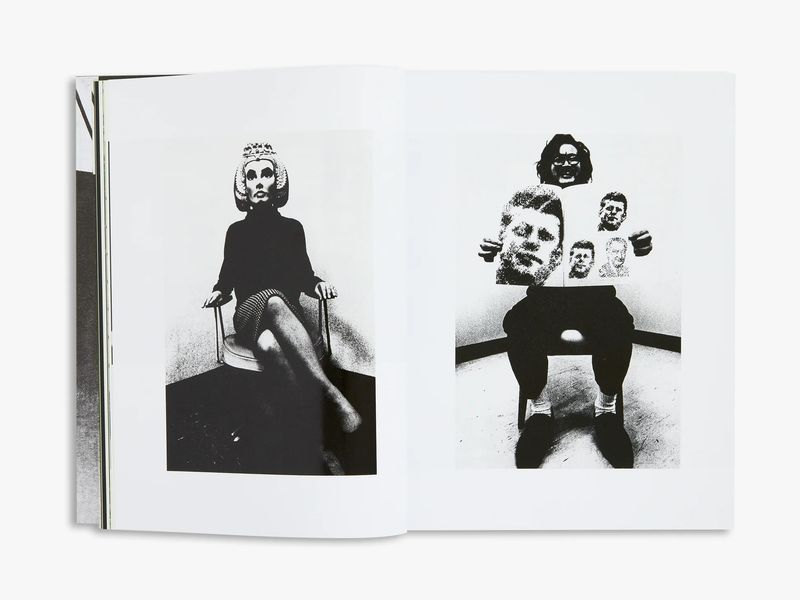

Quartet begins its survey of Moriyama’s early Photobooks with Japan, A Photo Theatre. The bulk of the images is taken from Moriyama’s trips to Tokyo theatres, to strip clubs, to the teeming streets of Shinjuku. It’s a book where traditional and avant-garde theatre meets with the everyday, the two melding into one.

We see his famous image of a woman in a bikini, standing on a winter roadside, the stripes of road marked against her unsmiling face and the bare branches of the roadside trees.

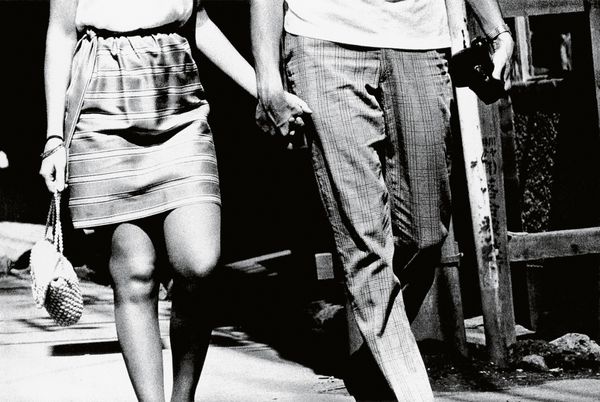

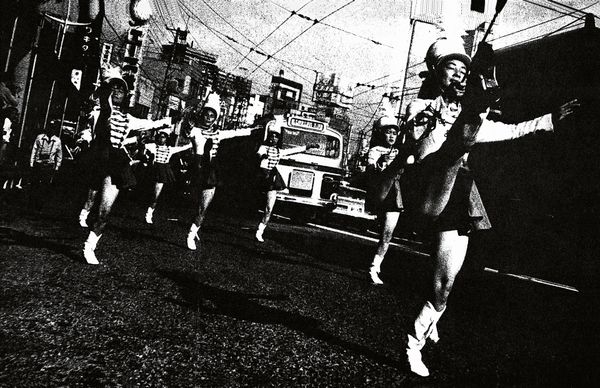

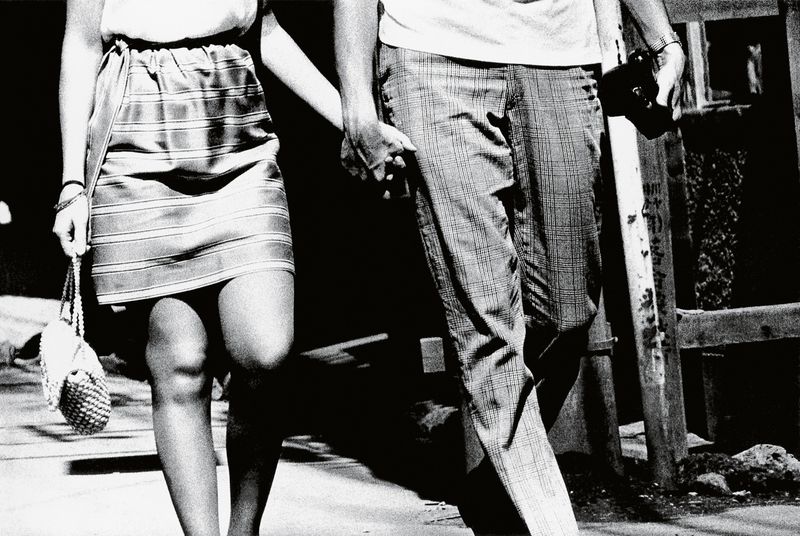

There are nods towards the post-war shift in Japanese culture (a culture, like that of Nazi Germany, which needed to shift) in scenes of Americanisation such as the high-kicking drum majorettes, the Lions International leather jacket, and best of all, the prim couple clutching what looks like (but probably isn’t washing detergent) as they stand all primly dressed like refugees from an American advertisement in front of some freshly built apartments, the horror at what-we-have-become transmitted through Moriyama’s brutally direct eye.

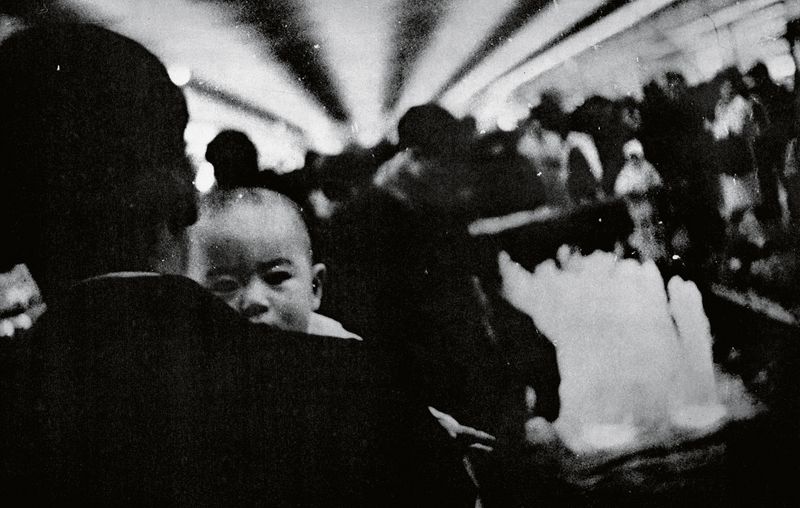

It’s an off-kilter world and it’s made even more off-kilter by Moriyama’s use of grain, blur, and out of focus elements (or are, bure, bokeh ) printed in extreme contrasts. His diptych of a plane taking off over an angled horizon of water, its fuels trailing behind into a grain speckled sky, and a man emerging from a becalmed sea all speak of a still but polluted world, one where the traces of Hiroshima and Nagasaki are evident on the page.

It's a style that has content, that doesn’t emerge from a vacuum but is tied to the history and psychology of a particular time, something that might be evident in the final images of the book, a collection of images of foetuses in a specimen jar.

In one of the accessible, entertaining, and informative texts in the book, the great designer Tadanoori Yokoo describes Moriyama’s working process: ‘…he returned to the same places day after day, taking pictures with one of those little cameras that have more than 70 frames per roll. He would go back to where we had walked before and casually click for the thousandth time. This reminded me of a dog habitually pissing on telephone poles to leave his mark wherever he went.’

That dog, that Moriyama alter-ego, appears in the next book, A Hunter. It’s another clipped-out image of a heavy-set street dog, the world on its shoulders appearing in profile to the camera. Together with Joseph Koudelka’s dog in the snow picture, it might be the world’s most dog-like picture of a dog. It captures the essence of dogness.

And maybe that’s what Moriyama’s work is all about. Maybe that’s what all great photography is all about. It captures what it means to be something, to understand something, to feel something.

Arthur Tress wrote in 1970, ‘Perhaps why so much photography today doesn’t grab us or mean anything to our personal lives is that it fails to touch upon the hidden life of the imagination and fantasy which is hungry for stimulation. The documentary photographer supplies us with facts or drowns in humanity, while the pictorialist, avant-garde, or conservative, pleases us with mere aesthetically correct compositions… Where are the photographs we can pray to, that will make us well again, that will scare the hell out of us?’

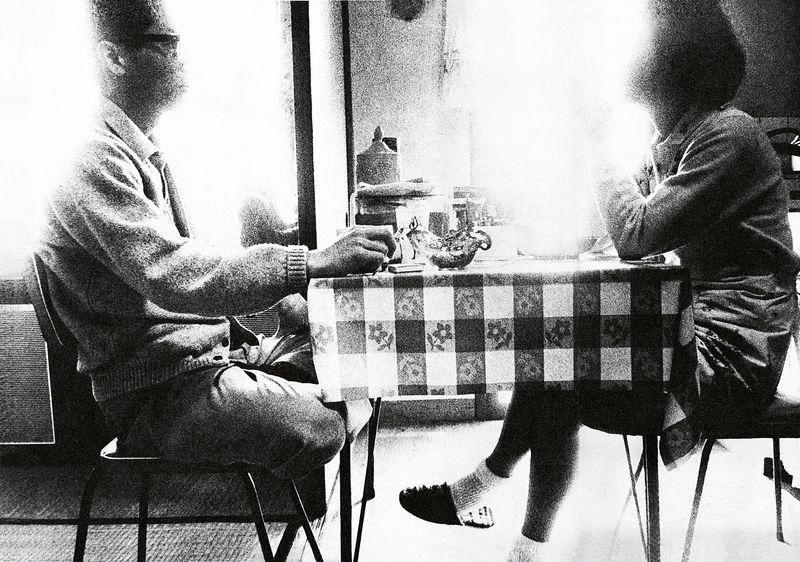

A Hunter was made during Moryima’s travels around Japan. Yokoo describes him as being a photographer who returns to his hometown but can never enter his: ‘His pictures create the feeling of going to one’s hometown and standing in front of one’s former house but being afraid to enter… Poor Moriyama can’t enter. He can only stand wretchedly in front of the door.’

That’s the entire book, a broad sweeping survey of Japan portrayed through its streets, its diners, its waters.

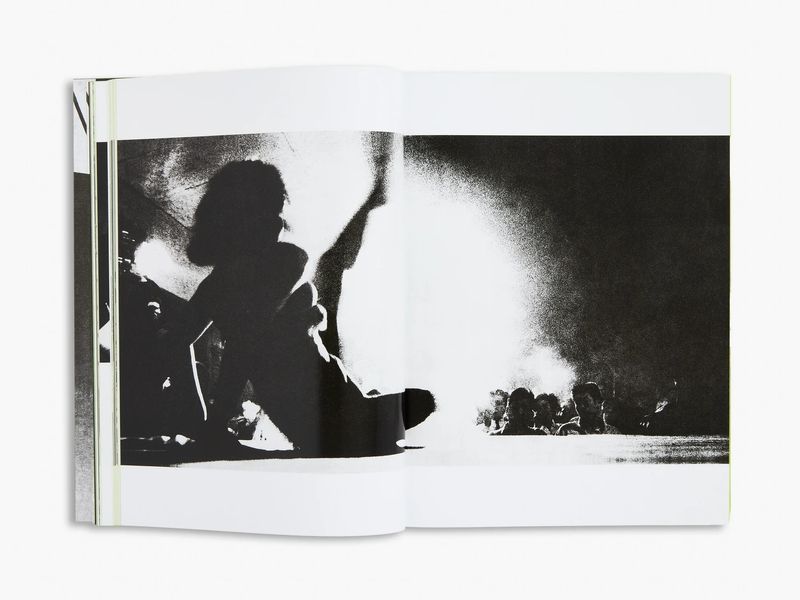

The flares of light, the shots of darkness, the sparks from a distant explosion range larger than in the previous work. We go more into detail, into the thingness of a tyre, a pair of lips, a rack of wristwatches. It’s a world scarred by chemicals, mechanicals, a chemtrail nightmare that finds a parallel in Japanese horror like Ringu, especially Ringu.

When there are flashes of humanity, they have a different quality of blur to them, one that distances, that places them in another realm. His hard flash picture of the woman fleeing barefoot down a rubble strewn alley couple with one of an unflashed, blurred couple playing in a field, is one example of the different quality of image working to great effect.

It’s a world of automatons where rows of tanning bodies are paired with lines of squid drying in the sun, where trains, and roads, and urban high streets are a symbol of our fall. It’s an accelerating world, one where things move faster and faster, a world of frayed synaptic endings, burnt-out retinas, and a certain paranoia, a world that might have a connection to the drugs that keep Moriyama awake during the night. And day.

As the pictures disintegrate and fall into the blur, and grain, and out-of-focusness, so does Moriyama’s faith in photography. The more he photographs, the more he repeats himself. As his friend and fellow photo-cynical member of the influential Provoke Collection, Takuma Nakahira wrote in his own work on the redundancy of photography (a subject that started with the invention of photography and is continuing to this day. It’s not new), ‘Extremely grainy images and intentionally unfocussed photographs in particular, have already become mere decoration.’

So Moriyama makes a book of all the off-cuts, all the rejects, all the failed photographs he has made and he calls it Farewell Photography.

‘Now I realise there was an overabundance of everything, in both my work and my private life, that led to this work. There was an emphatic desire to wave goodbye to my own and other people’s photographs. This helped with a prompt decision on the title.

Once I had the title, I began to collect the negatives. My attention was caught by those disregarded shots at the end of rolls of film. I instinctively picked out those I found weird or odd in some way. I separated out anything with a clearly discernible image. The book was to be a collection of curiosities for which I even gathered, scrapped and trampled negatives from the darkroom floor. There isn’t a single picture that was taken for this book.’

So it’s the photographic equivalent of white noise, a musical equivalent might be some early Velvet Underground. It’s interesting. But it’s not Burt Bacharach. If you’re looking for some easy viewing, don’t come here.

Flash forward to 1982, and the final book appears. It’s Light and Shadow, and the same themes appear as in previous works. But they come without the fire, the angst, the obsession. It’s the outlier in the series.

There have been reprints made of most of these Moriyama books over the years, but they are expensive and sell out quickly. This is a great introduction to the key works of Moriyama, the books that make him what he is, when being blurred, grainy, and out-of-focus felt like more than just the ‘mere decoration’ that it so often is today.

--------------

Quartet by Daido Moriyama is published by Thames and Hudson

Pages: 440 pp

Format: PLC (no jacket)

Illustrations: 250

Publication date: 2025-08-28

Size: 29.5 x 21.7 cm

ISBN: 9780500027882

--------------

All images © Daido Moriyama

--------------

Daido Moriyama was born in 1938 in Osaka, where he studied photography before moving to Tokyo in 1961. He worked as an assistant to photographer Eikoh Hosoe and began to produce his own collection of photographs depicting the forgotten areas and darker sides of his home. Many of his early photographs were influenced by the ‘Provoke’ group, which published three magazines illustrated almost entirely with photography. Moriyama joined the movement for the second issue of the magazine which, in addition to its political aims, came to solidify a type of Japanese aesthetic for ‘grainy, blurry and out of focus’ images, embracing a tradition of experimental image making and rebellion against the technical precision promoted by the culture of the time. His early work captures life during and following the American occupation of Japan after World War II; in particular, the effects of industrialisation and the consequential shift in urban life in which some areas were left behind the rapidly changing city.

Colin Pantall is a photographer, writer and lecturer based in Bath, England. His next online courses and in person workshops begin in January, 2026. More information here. Follow him on Instagram.