Photobook Review: I'm So Happy You Are Here

-

Published14 Nov 2024

-

Author

- Topics Photobooks

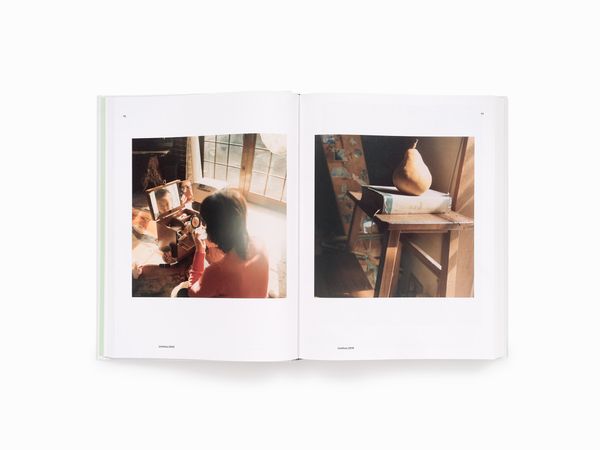

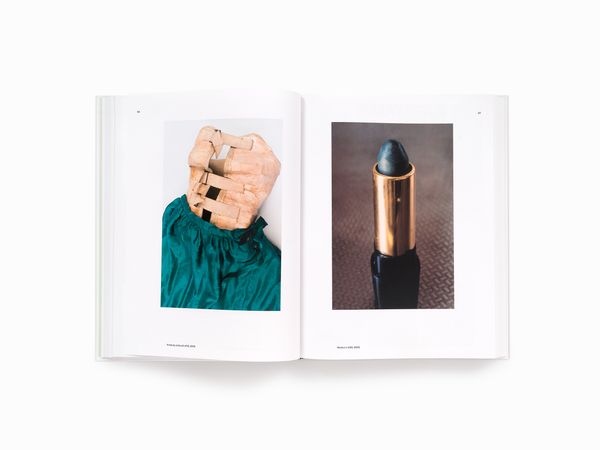

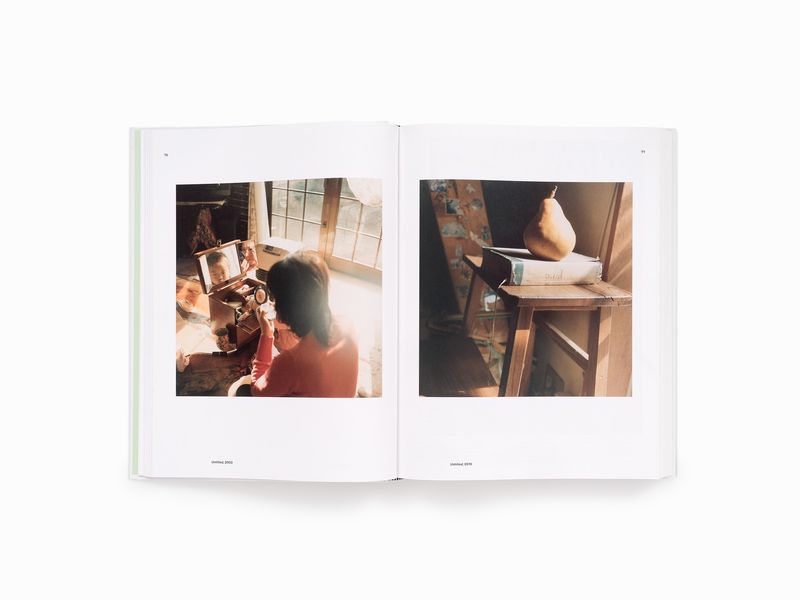

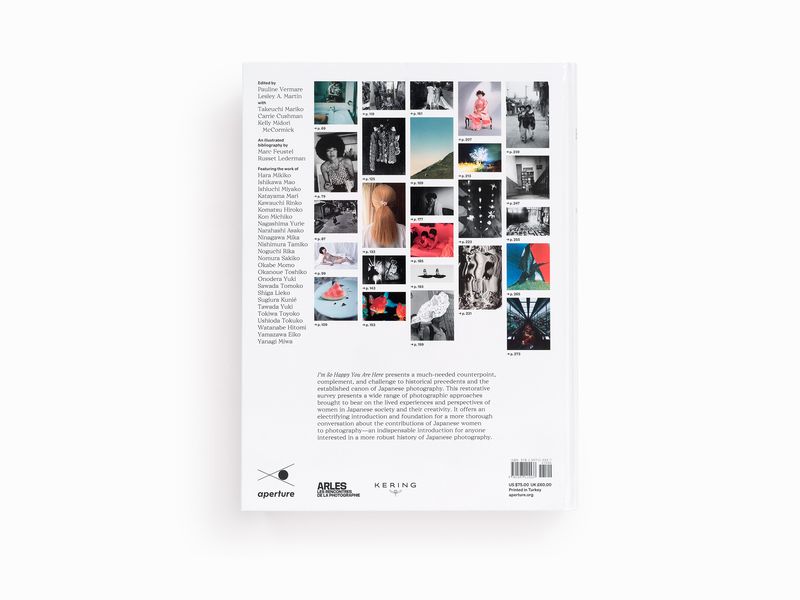

I’m So Happy You Are Here: Japanese Women Photographers From The 1950s To Now is a book featuring work by Japanese women photographers. It’s a book where ‘traditional’ gaze are reversed, identities examined, and the language of photography questioned.

In 1976 the Japanese photographer Ischiuchi Miyako organised the all-woman exhibition, One Hundred Flowers In Bloom in Tokyho. It was a response to the commonly held male idea that a woman’s place was in front of the lens, not behind it.

This was part of a wider division of social roles that extended to political protest. “In 1968 the men were on the barricades while the women were kept in the kitchens,” Ischiuchi said. “Uprisings were always led by men, and this traditional allocation of roles didn’t sit well with me. So I quickly gave up on that commitment. On the other hand, I was engaged in the women’s liberation movement from its very beginning.”

Ischiuchi’s all-woman exhibition was part of an early fight for photographic equality, and it was one that wasn’t accepted gently. In 1986, when Japanese male photographers discovered that the curator Ricardo Viera was planning on including women photographers in an exhibition, they threatened to withdraw. Viera paid no heed to their threats and instead curated the first institutional exhibition of Japanese women photographers in the United States.

I’m So Happy You Are Here is a continuation of that tradition of opening opportunities to women photographers. It’s a book in which ideas of sexual agency, the role of women in Japanese society, and a questioning of the male gaze go together with representations of political protest, the elemental nature of the nature, and the complexities of diversity in Japan.

That questioning of the male gaze can be seen in Sasamoto Tsuneko’s 1952 image of a woman glaring at an American soldier next to her on the ferry they are riding. It is an image that hints both at a hostility to the occupying forces, but also to the epidemic of sexual violence that appeared around their military bases.

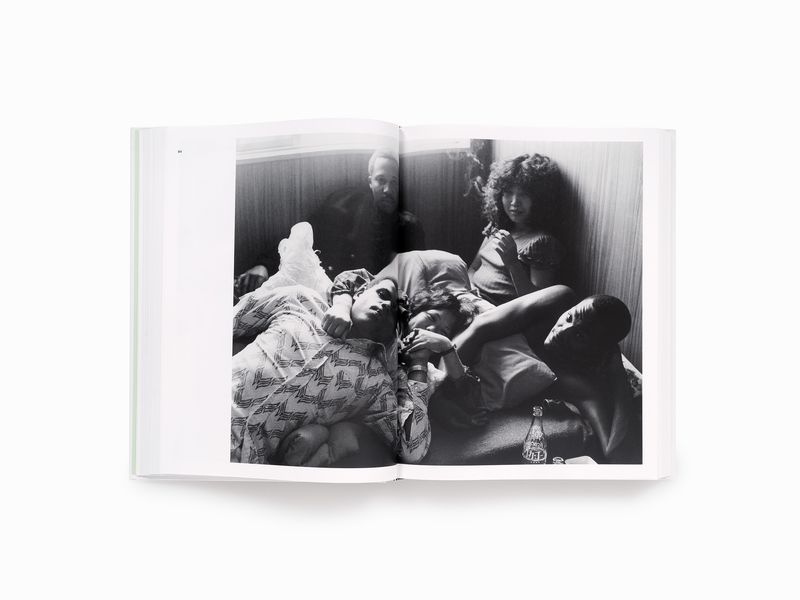

Ishikawa Mao took an immersive approach in her series Akabanaa (Red Flower), becoming part of a bar girl community at an African American bar in Okinawa. “There was a freedom to say what you wanted and live your own life. That is why these women lived freely; they were joyful, powerful, and strong. Before I knew it, I had become one of them.”

Nagashima Yurie features with work that questions male portrayals of women. She says “…the self-portrait means that you can take on both roles, as a model and as a photographer. When you have a camera on a tripod, you have the space in front of the camera and also the space behind the camera. It’s very symbolic. It’s a way of taking action against the historical roles of the male and female in photography.”

Yanagi Miwa’s Elevator Girl House 1F from 1997 looks at traditional gender roles in ‘elevator girls’ (and see Robert Frank’s photograph for a US equivalent). She said, “Suddenly I saw these women, who were continuously performing their role before the audience that is the society at large, in relation to myself, as I was now alone with no place in society. I became interested in women who had to act like robots reciting their given words and actions over and over in a ritual-like way, and I decided to do a work based on this image.”

The idea of the autobiographical Shishōsetsu (or I-Novel) is apparent in the hugely influential work of Hiromix and Okabe Momo, a photographer who has worked with queer identities in Japan. “As my photography is based on, the Japanese I-novel, it is always made up out of my own, actual, experiences,” says Okabe. “I don’t decide in advance what I am going to photograph. And while I work from my private life, I hope that my work shares its power with many other people – and that it continues to positively resonate within them as part of their lives, too.”

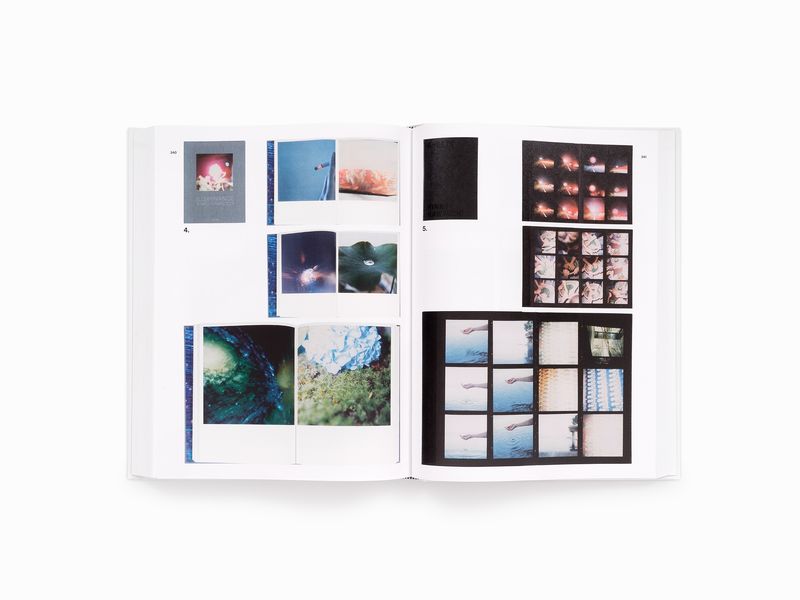

Komatsu Hiroko who is best known for intensely textured work, also delves into the autobiographical with her Instant Diary, a work that combines the archival with the banal in her text image catalogue of her everyday life.

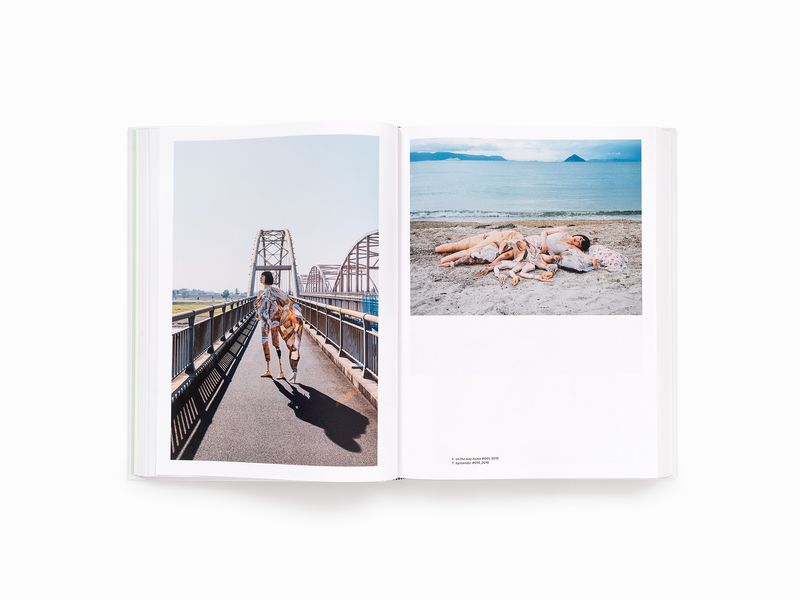

I’m So Happy You Are Here includes the ‘everyday sublime’ of Rinko Kawauchi, the brilliant psychological landscapes of Shiga Lieko, and the wonderful Half Awake And Half Asleep In The Water by Narahashi Asako.

The book is accompanied by a bibliography of women’s photobooks from the 1950s to now, which sits somewhat detached from the main body of the book. There are also multiple texts, in particular the main essay by Pauline Vermare. In this, she talks about the gendering of the Japanese language, how a woman is expected to speak like a woman. Vermare quotes featured photographer, Nagashima Yurie: “The female way of talking doesn’t sound strong enough. It’s not designed to win. It’s the language to give it up for your owner; father, husband, or son, any kind of male figure.”

With her words, Nagashima challenged that idea. And with her images, she challenged the ideas that a woman’s place is in front of the lens, her body, her desires, her life subject to whatever the male photographer deems it to be. And that is what I’m So Happy You Are Here aims to do; change the way Japanese photography (and photography as a whole) is seen, understood, and ultimately made.

--------------

Contributors: Pauline Vermare, Lesley A. Martin, Takeuchi Mariko, Carrie Cushman, Kelly Midori McCormick, Marc Feustel and Russet Lederman

Hardback cover

8.25 x 11 inches

440 pages / 518 images

Publicated on 17.09.2024

ISBN: 9781597115537

--------------

Colin Pantall is a photographer, writer and lecturer based in Bath, England. His next online courses and in person workshops begin in January, 2025. More information here. Follow him on Instagram.