Photobook Review: I Carry Her Photo With Me by Lindokuhle Sobekwa

-

Published27 May 2025

-

Author

- Topics Photobooks

I Carry Her Photo With Me is the story of Ziyanda, the photographer’s late sister. It’s the story of Sobekwa himself as he searches amidst his sorrow and guilt to piece together who she might have been, and it’s the story of South Africa itself.

The book starts with a group photo of Sobekwa’s family, the face of his sister a blank white space where his mother has cut it out.

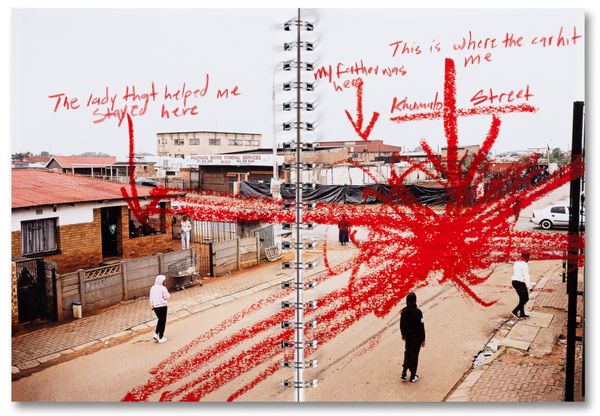

The memories Sobekwa had of her are sketchy, but she was tough, a rebel, that much he can remember. She was brought up by her grandmother in the countryside, and then she disappeared from his life after the 6-year-old Sobekwas broke his back in a hit-and-run accident.

We see a contemporary image of the street where it happened, with red crayon text filling us in on some of the details. It’s Khumalo Street in Thokoza, a township built to service apartheid-era ‘racial capitalism’. The street is worn-out and dusty, the low-rise buildings fitted with corrugated iron rooftops rising above brick walls. There’s a funeral parlour in the background, a black tarpaulin stretched across some derelict land, a shopping trolley and an old mattress lying on the pavement in the foreground.

Ziyanda disappeared from her brother’s life for ten years, but then they found her, exhausted and sick in a nearby hostel, scars across her back. She returned home and the family cared for her as best they could, her mother returning home two days a week from her work, ‘attending to the needs of the white family she served’.

One day, Sobekwa tried to photograph her. “If you take this photo,” she said, “I’m gonna kill you…”

“I still wish I’d taken that photograph,” he says. “But I respected that she didn’t want me to take it.”

Soon after, Ziyanda died. It was cold, there was foam coming out of her mouth, and the family mourned.

All that was left of her was that one fragment of a photograph of the family taken at Christmas time - they cut the square out and enlarged it. His mother kept a copy in her bible. ‘I like to imagine that the square of Ziyanda’s face rested in the Gospel of Luke…. where Mary Magdalene is first introduced…’, Sobekwa writes in an accompanying pamphlet of text.

He found the phone numbers of people she had known on the back of the photo and began to trace the details of her life. People told him, ‘’…that Ziyanda was involved in a gang, that she was deep into alcohol and drugs, that she was a prostitute.’

And so Sobekwa goes on a voyage of discovery in the hostels, the streets, and the landscapes around his Thokoza home. He photographs the women Ziyanda knew, searching for his sister in the faces that he meets.

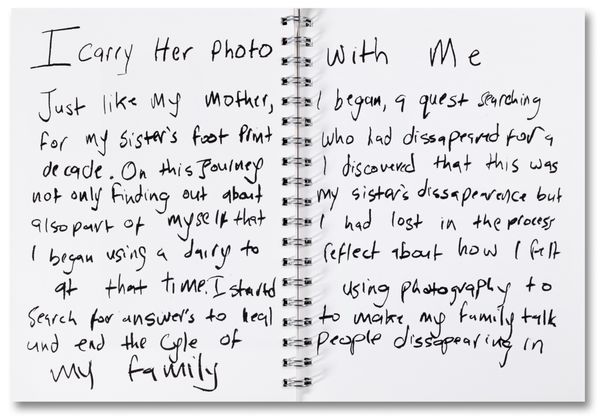

The results are put together beautifully in this book. Spiral-bound, taking the form of the kind of notebook you write your thoughts in, you make a ready-made dummy from, it sketches out people and places and a sense of absence and loss. Nothing is pinned down and it doesn’t have to be (an accompanying pamphlet of text gives further contextual detail).

‘I felt I was seeing Ziyanda in her friends,’ he writes in the book, thick felt tip pen spelling out the words next to a picture of a woman standing by a window, the paint peeling off the wall, a clothes peg holding the curtain in place.

We see the exterior of a hostel in the next picture. ‘This is the hostel where my sister Ziyanda was found,’ the felt-tip pen writes.

There are more interiors of hostels; friends and acquaintances of Ziyanda lying down and getting changed within the confines of small spaces curtained off for a semblance of privacy, young men sprawled outside dark doorways.

Different interiors appear; beds set against bare brick walls, the mortar oozing out into the room interior, Sobekwa’s mother sitting on her bed, the family photo with the missing square of Ziyanda’s face leaning on the iron-sheet wall behind her.

It’s a story of housing then. And home. And the difference between a ‘matchbox house’, an ‘iyotyombe’ – the shack that was set up in somebody’s back yard that Sobekwa lived in for much of his life, and a tent (and which his family probably lived in when their shack burnt down).

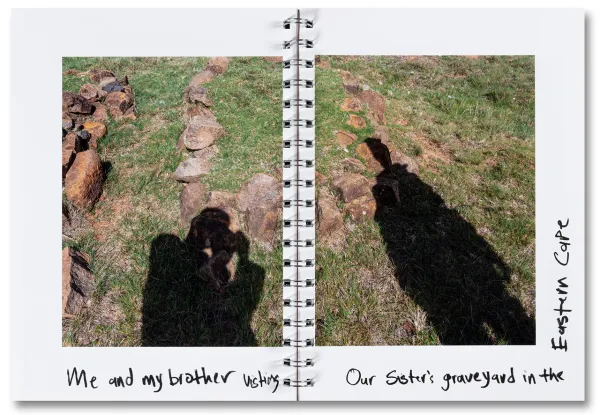

We see these homes, and the streets, fields, and edgelands they are set in. Sobekwa travels to the farm where his sister grew up and migration and displacement from the land are folded into the narrative.

The history of the apartheid era is also embedded in this story; the role of the township of Thokoza as a black service satellite to white Johannesburg, the cramped housing and lack of transport, housing, and infrastructure, the underlying gang violence, drugs and prostitution, and the sense of unbelonging that pervades throughout the book.

It’s an unbelonging that has its roots first in colonialism and then in apartheid; the separation of people and the places they sleep, they work, and they call home, the creation of artificial townships, and the necessity for people like Sobekwa’s mother to care for other richer, whiter families at the expense of her own.

But it’s also about Sobekwa and how it makes sense of the world that he lives in. The last snippet of text reads, ‘I have searched the streets, I have searched in my family, trying to find Ziyanda. I realized that the search was not only about her but it was about finding myself.’

--------------

I Carry Her Photo With Me by Lindokuhle Sobekwa is published by MACK

Spiral-bound hardcover

18 x 22cm, 80 pages

ISBN 978-1-915743-312

--------------

All images © Lindokuhle Sobekwa

--------------

Lindokuhle Sobekwa (b. 1995 in Katlehong, Johannesburg) is a South African photographer. He was introduced to photography in 2012, through the Of Soul and Joy Project in Buhlebuzile High School in Thokoza township, where his photography mentors included Bieke Depoorter, Cyprien Clément-Delmas, Thabiso Sekgala, Tjorven Bruyneel, and Kutlwano Moagi. Sobekwa was announced the 2025 Deutsche Börse Photography Foundation Prize winner with his first photobook, I Carry Her Photo With Me, a photographic search for answers about the disappearance of his sister Ziyanda, which was published with MACK in 2024. Sobekwa lives and works in Johannesburg, South Africa.

Colin Pantall is a photographer, writer, and lecturer based in Bath, England. His next online courses and in-person workshops begin in October 2025. More information here. Follow him on Instagram.