Photobook Review: Cursed by Charlie Engman

-

Published12 Mar 2025

-

Author

Referencing the online trend of “cursed images”, Engman’s work asks us to view AI-generated pictures as images in their own right: what are they capable of expressing, and what are they trying to say about the world?

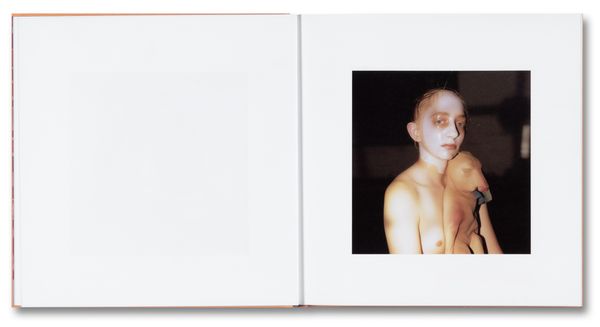

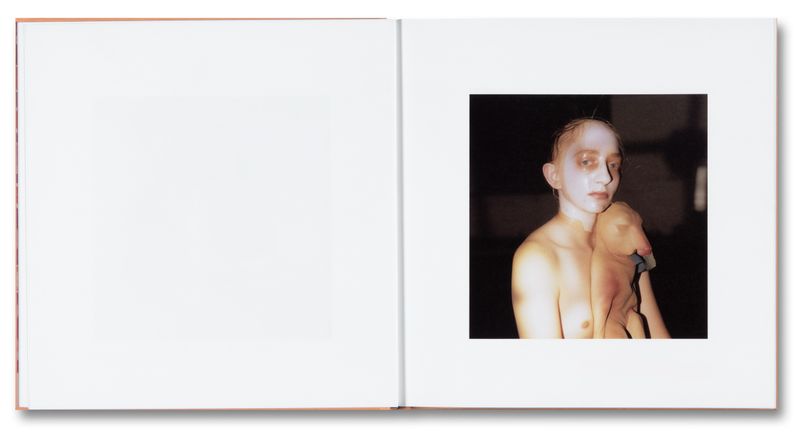

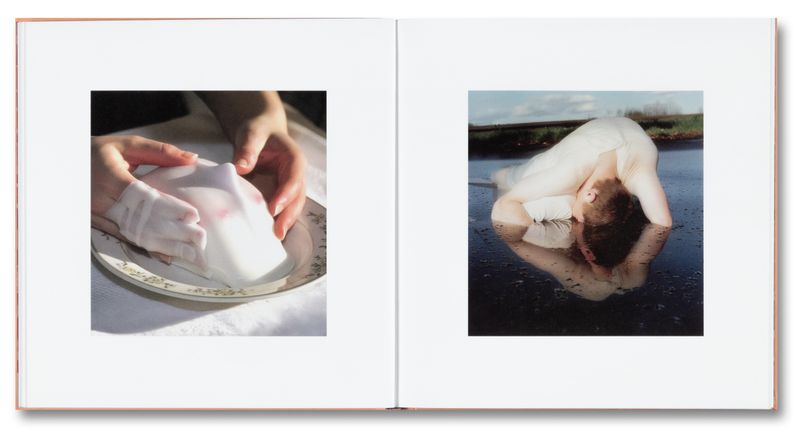

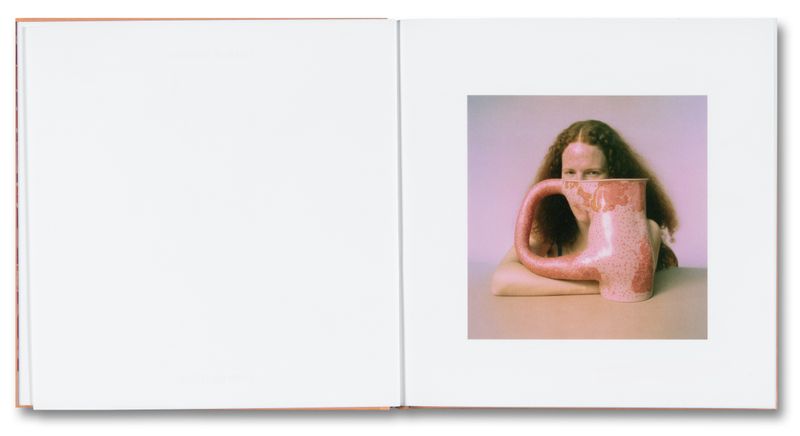

Published by SPBH Editions, Charlie Engman’s Cursed is a book of bodies in search of a stable form. It is a story of metamorphosis from one state of matter to the other. Identities slip into skins made of rubber, wax, plaster. The way physical entities – bodies, vegetables, insects, water, grass, and so on – interact with each other feels twisted and intertwined. Everything has melted and was molded into a slightly different version of itself. How did we get here?

Each time I look at this book, I find images that seem completely new. It feels as if they were figures with multiple facets, and a different one emerged at each look. I get the sense of a newly-born world, teaching itself how to be: How do fluids behave? How do surfaces collide? How do hands touch?

Charlie Engman’s interest in AI lies at the meeting point of its accurate and inaccurate representations, of its successes and failures. “There is a symbiosis there that I wanted to explore. Unlike photography, generative AI doesn’t have a direct relationship with the physical world—it is one step removed. It represents reality through representations, learning from photographic imagery rather than direct experience. What do you get wrong if you don't understand the physical world from an experiential perspective? And what, on the other hand, do you get right?”.

The human and non-human beings in Cursed often convey a sense of alienation. They are lonely figures seemingly trapped in a state of matter that isn’t their own. Yet, they can be tender and sensual too, expressing a longing for touch, and love. In the background is a latent sense of paranoia, as if we were being observed and followed. Groups of male figures, all dressed the same, appear at the edges of several images. Something horrible might be about to happen, or have just occurred. “I’m interested in that strange, uncanny valley where there is something I don’t fully understand, and that feels different. A mystery, yet anchored to something that I do understand. I’m trying to find that sweet spot where the image is not so crazy that I feel alienated by it, yet it’s not so familiar that I’m bored. It’s a sort of middle ground where I’m destabilizing something extremely familiar. Suddenly you walk to the other side of it, and you’re like – I’ve never seen that part”.

We might feel something similar when looking at a “cursed image”. The term was coined in 2015, originating from a Tumblr blog of the same name where disturbing, mysterious pictures were being uploaded. “Cursed images seem to emerge from a primordial soup, arising out of the dark”, says Engman. “They feel like they have no author. They have a hyperreal quality, they are usually degraded, pixelated, or poorly lit. They look like they were taken with a cheap camera, lacking skill, yet they hold a raw power. I think that’s what makes them beautiful—they feel almost spiritual. People call them cursed because they seem magical, like we cast a spell, and they appeared. As an image maker, I was always jealous of them. Could I create something like that? With AI, I found that I could. Also, AI-generated images have that same authorlessness, because of their randomness and the way they pull from the entire world’s data”.

The term “curse” easily relates to the concept of AI – or, better, to the way our society absorbs it. “Many feel like we're cursing ourselves by creating something that could lead to our own undoing. That fear—that we’ve made the thing that will destroy us—was something I found interesting”, says Engman. Yet, his perspective on AI as an image-making tool is rather out of this debate. Or, just as the images in Cursed do, it overturns the conversation, flipping it inside out, so that it stops making sense. And that different questions start rising. “The discourse around AI tends to be very abstract – its impact on society, art, and creativity. Instead, I wanted to ask: what is it actually doing right now? What is it capable of expressing? What do these images make us feel? What are they saying about the world, what are they trying to talk about?”.

Looking at the essential differences between photography and AI can help us answer these questions. “Photography represents what something is, while AI tries to understand how something works”, says Engman. “In photography, you’re capturing something that exists. With AI, there is no real object. For example, if I prompt AI to generate an image of someone hugging a bird, there’s no actual bird, no person, and no physical interaction taking place. Instead, the machine has to infer everything: What is a person? What is a bird? What does “hugging” mean in relation to these entities? What is the size relationship between them? How does light interact with feathers, and to human skin? AI has to build an entire network of relationships from, essentially, nothing”. After Engman, this process has more to do with our expectations than with anything else. “AI is not just mimicking reality—it’s attempting to understand what we expect from it. It learns because we tell it it’s doing a good job – it is actually constantly trying to please us. That’s what fascinates me: AI doesn’t show us reality, but rather, it reveals what we think reality looks like. People's strong reactions are, eventually, reactions to their own expectations.”

If we wanted to look at AI images and evaluate them as no more, no less than images, a photobook would be the most suited medium. “It forces a different kind of engagement. It gives space, and a material reality to the images, encouraging the viewer—and myself—to consider them individually”. The design of Cursed makes a seamlessly standard photobook, equating AI images to photographs. “I wanted the book to resemble what AI might think a photobook should look like. The text uses AI-generated fonts. The format is square, because that’s the default for generic photobooks you’d order online. Even the endpapers follow a classic marbling pattern, reinforcing that conventional aesthetic”. The AI-generated marbling pattern enclosing the book reminds me of the “primordial soup”, as Engman called it, from which cursed images emerge. It feels like an undistinct, boiling liquid where all the creatures in the work take shape. This is where everything begins and ends.

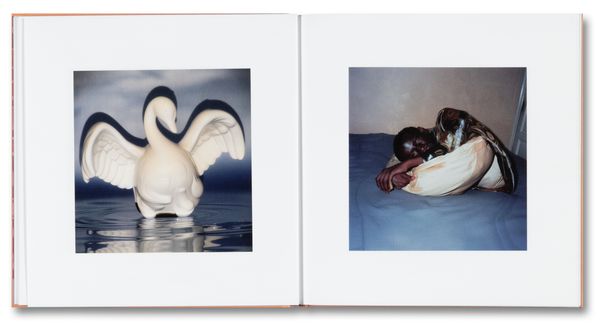

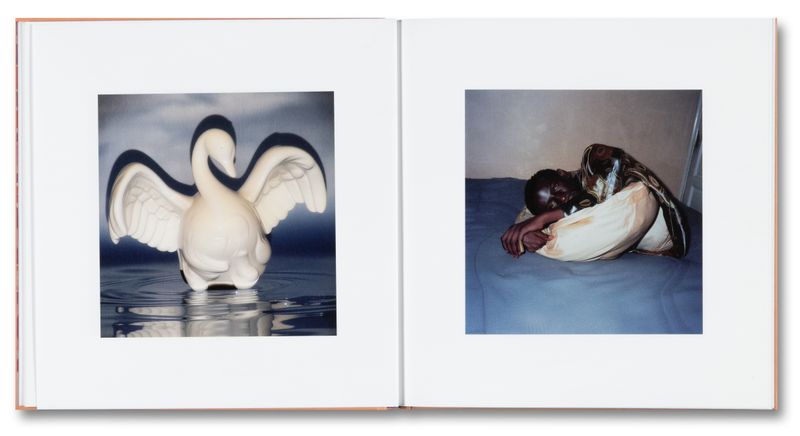

Liquid shapes are a constant in this book - lakes, swimming pools, ponds, the sea. And so are swans. “I just love how AI renders water – I find it beautiful and surprising”, says Engman. “Also, there is a long history of what water means to people, and of its allegories in poetry, painting, or photography. The same goes with swans; they have a poetic, regal, romantic quality that we project onto them”. However, what Engman is mostly interested in is the relationship AI has to clichés. “People think of AI as a cliché machine, which provides the most obvious, basic version of reality. If you wanted to make a swan, it'd return the most postcard version of it. And that's somehow not interesting nor artistic, because it's so obvious, right? What I want to do is ask: Why is it so obvious? What's the difference between an obvious swan, and a surprising swan? Also, I think clichés are really important things to look at”, he adds, “since they have some really deep, strong core that everyone relates to. I think a cliché is a sort of scab that has grown over something really beautiful, turning it into something ugly. And I think AI can work like a scalpel. You can take visual tropes, such as water, or swans, and iterate them a bunch of times, deconstruct them, pull them apart, wash them together, and try to reinvest them with the kind of beauty that I think they innately have, which was lost through overuse and repetition. I’m trying to find a way to look again at things we can’t stand looking at anymore.”

Often, bodies and shapes in Engman’s work seem overgrown. A chunk of bread looks like it was genetically modified. Wings are developing from somebody’s arms. We see over trophic muscles and breasts, a clay face emerging from the surface of a vase. “AI is a prothesis”, Engman says. “It is a way to do humanity as a non-human. How do we make this entity perform humanity? Think of AI therapy, for example. It's all about mimicking human communication. In that sense, AI acts like a puppet, exaggerating human behavior like a cartoon. A cartoon character can stretch, break, or grow two heads. It can do something a human can’t do, but in a way that we can relate to”.

I go through Cursed one last time and what I see is a set of characters performing a desperate attempt at being human. Or maybe, looking at the same concept from a different angle, what I see is reality trying to transcend humanity. Pulling, stretching the edges of what we can be. In between these two versions of the same story is a glitched world, one that might look like ours yet is profoundly different in essence. We couldn’t photograph it, but we could make it emerge out of connections, prompts, deviations, randomness, and reiteration. I am reminded of a quote whose author I cannot recall. It says: “There is another world, and it is in this one”. Searching for its source on Google, I see it is at times attributed to Paul Éluard, at times to Rainer Maria Rilke. Across its various transcriptions, instead of “and” we often read “but”. Eventually, I come across an article highlighting a possible source: it is Paul Éluard citing Ignaz-Vitalis Troxler, who himself was citing Albert Béguin. A quote of a quote. To trace its purest essence one needs to dig back, trying to spot a version that allegedly preceded its iterations. The original thought. Yet, a more interesting reading might be found precisely here. In this primordial liquid of mixed knowledge, at the intersection of different minds who made an idea their own, and different hands who wrote it down, taking one word for another, transitioning a thought into a slightly different one, until it became nobody’s, and everybody’s at the same time.

--------------

Cursed is published by Self Publish Be Happy Editions

Embossed hardcover with tip-in

22.5 x 22.5 cm, 112 pages

ISBN 978-1-915743-58-9

-------------

All images © Charlie Engman

--------------

Charlie Engman (b. 1987) is a Brooklyn-based photographer, director, and art director whose work pushes the limits of traditional image making, simultaneously principled and irreverent — imbued with both the weird and wonderful. Engman draws inspiration from his degree in Japanese and Korean studies from the University of Oxford and his training in modern dance. His previous book MOM was published by Edition Patrick Frey in 2020.

Camilla Marrese (b.1998) is a photographer and designer based in Italy. Her practice intersects documentary photography, design for publishing and writing, aiming for the expression and visual articulation of complex issues.