Lucija Rosc On Her Exhibition Six Stations And A Golden Tooth At PhMuseum Lab

-

Published23 Sep 2025

-

Author

Selected through the PhMuseum 2024 Women Photographers Grant, Lucija's work was exhibited in Bologna as a non-linear path reflecting on the rules and influences that shape us.

What are the dynamics entangling generations and what is left of them when the elders leave? How can we carry the legacy of those we love into the future? How much of who we are derives from the education we had at home and that of our school system? The Slovenian artist offers no answer to these questions. They are rather a trigger to develop her research through playful, ambitious, and sometimes desperate attempts to understand.

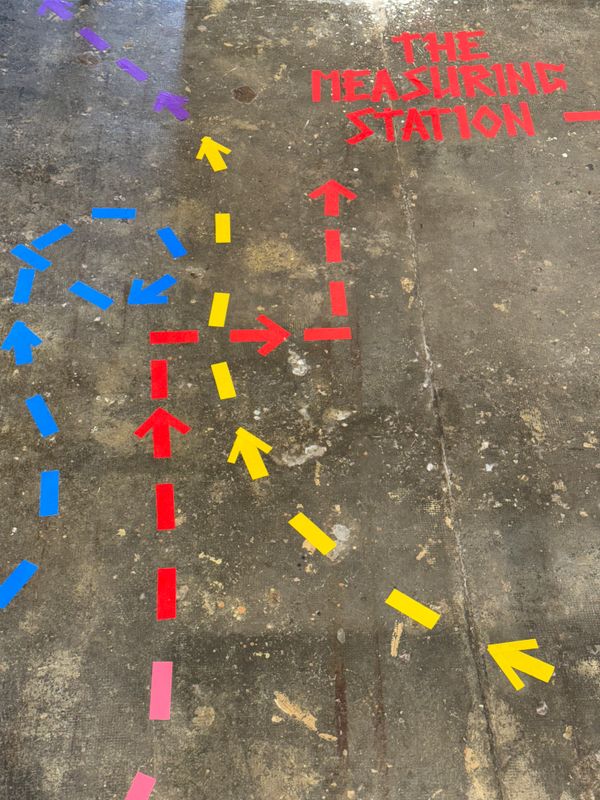

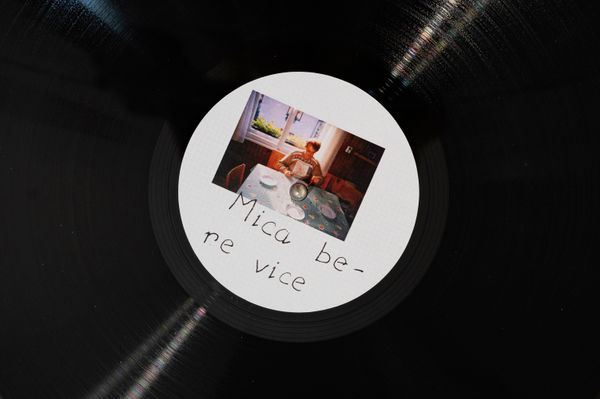

Six Stations and a Golden Tooth presents her work across six stations, which display different layers of her research. Visitors can follow a thread on the floor and follow the progressive order - or simply break the rule and move around. From the story of a tooth exchange at Station 1 to a vinyl engraved with grandma Mica reading her collection of jokes at Station 6, the exhibition stimulates a reflection on how family values and the school system education influence the person we are today – while remembering the importance of playing and sharing.

With the 2025 Women Photographers Grant's applications closing on 2 October, we touched base with Lucija Rosc to discuss the creative process and themes behind her exhibition at PhMuseum Lab.

Ciao Lucija, since 2020, you have been collaborating closely with your grandparents to develop a wide range of different projects. How did this whole process start, and how did it evolve throughout the years?

It started very naturally. I didn’t go to kindergarten, so I spent a big part of my early childhood with my grandparents while my parents were at work. That time gave me space to play, observe, and just be. There was no pressure, only attention and care.

Years later, I started realizing how deeply that shaped my creative thinking and sensitivity. My projects with them weren’t “projects” at first, just everyday interactions… Over time, I started recognizing how powerful those simple, repetitive acts were, and they slowly transformed into artworks. The collaboration has become more intentional but still remains intimate and full of affection. It’s not just about documenting them, but also about co-creating something together, often through humor and playful gestures.

The exhibition’s Station 4 features a magnified Noma ruler, reproduced in a 1:10 scale. The piece is drawn from your most recent body of work, The Rules Of The Game (2024-), which addresses the constraints and standardization of school education, and the importance of play. What do you think was the influence of these two aspects on you and your practice?

This series comes from a very personal place. I used to keep the original Noma 1 ruler in my childhood room, and it became this strange symbol of both control and creativity. On one hand, it is something playful, but on the other, it embodies the rigid expectations of school, measurement, and perfection. The enlarged version (Noma 1, 10:1) is a humorous and almost absurd reimagining of that object. It points to how we internalize certain rules very early on, especially within institutional spaces like schools, and how those rules continue shaping us well into adulthood. I often find myself negotiating between the need to let go and the instinct to over-control—even my memories.

In my practice, play is a way to resist rigidity. I see humor and imagination as serious tools to navigate adulthood. The Rules Of The Game reflects this constant tension between structure and freedom, between wanting to follow the rules and needing to rewrite them. I think I’m always trying to find a balance between those two forces, both in life and in my work.

The show brought together five different projects, exhibiting them in a non-linear path for the first time. How did you perceive seeing your works collectively, following PhMuseum’s curatorial interpretation?

It was very touching for me. I usually show these projects separately, so seeing them together, interacting with each other in one space, was surprisingly emotional. It felt like a visual map of everything I’ve been thinking and feeling over the last few years. I really appreciated how the PhMuseum team created a layout that embraced play and movement, but also made room for intimacy. It felt like walking through different emotional stations; some funny, some nostalgic, some more reflective.

From interactive stations to a labyrinthic path guiding people through the works on show, how did you feel about the public engagement with the different media in this exhibition?

It was a joy to see how people moved through the exhibition space. I loved how they didn’t just observe the works but interacted with them. At Station 4, where the oversized Noma 1 ruler was placed, people stood next to it and measured their height, just like we used to do as kids (on the doorframe or somewhere on the wall). It was a simple gesture, but full of nostalgia and playfulness. That’s exactly the kind of engagement I hope for; a little silly, but also connected to memory and self-reflection.

Another great moment was seeing visitors interact with Building Blocks 1/2, which was part of Station 2. The installation includes a miniature table tennis table with hand-painted wooden objects, and people could move and rearrange the elements to create their own sculptural compositions. Overall, the layout invited a kind of wandering that mirrored the themes of the exhibition itself, moving between memory, structure, and imagination. I think it sparked curiosity and loosened the usual stiffness of a gallery space.

Station 5 displayed works from your series Thickening, where you take on the role of a curator constructing a collection of your grandparents’ items. Can you tell us a bit more about the pieces, and your approach in curating them?

In Thickening, I took on the role of curator by working with objects my grandparents have collected and kept over the years. The series is about trying to make sense of things that don’t necessarily make sense at first glance. It includes everything from knives and dog-themed cardboard cards to newspaper clippings, pieces of foam, shoes, and even empty plastic bottles. I was interested in how they assign value to these everyday objects; whether sentimental, practical, or visual, and how these values shift across generations.

For example, Bathroom Floor Mat and Mica’s Newspaper Cutouts feature clippings that my grandmother Mica, has obsessively collected over the years. We pinned them onto worn bathroom mats from their home, turning them into fragile and slightly absurd displays. Other pieces reflect a similar approach. Puppies On Tapestry is a woven work my grandmother began as a gift for my primary school graduation but only finished after I completed high school. Wood, Shoes, Foam is a site-specific piece made from materials I found in my grandparents’ garage, including my grandmother’s unused gym shoes from her teaching years.

The title Thickening comes from the Slovenian word podmet, a flour and water mixture my grandfather uses to make one of my favorite dishes, carrot soup. For me, it became a metaphor for holding together scattered pieces and creating something meaningful out of them. Thickening is not a conventional archive, it’s intuitive, emotional, and shaped more by habit and memory than logic.

How was your overall experience visiting PhMuseum Lab and Bologna, accompanied by your entourage of friends and fellow photographers from your collective in Ljubljana?

It was amazing. I felt so welcomed by everyone at the PhMuseum Lab and loved sharing the experience with my friends from Ljubljana. It really made everything feel like a celebration. Bologna itself was beautiful, and I especially appreciated the warmth and energy of the local community who came to the opening. I hope I'll be able to return for the finissage in September.

Do you have any advice for future applicants of the PhMuseum Women Photographers Grant?

Uhh, that’s always a tough one, haha. I’d just say, be honest and put your full self into the application. It really helps when the work comes from something that means a lot to you. Don’t be afraid to take risks and trust that your voice and story matter. In my experience, people connect most with work that feels personal and sincere, even (or especially) when it’s not perfect.

----------

All images © PhMuseum

----------

The PhMuseum Women Photographers Grant, now in its 9th edition, aims to empower the work and careers of female and non-binary professionals of all ages and from all countries working in diverse areas of photography. Its mission is to support the growth of the new generations and promote stories narrated from a female perspective while responding to the need to work for gender equality in the industry. This year, PhMuseum Lab will offer a new solo show to one work selected from our open call. You are welcome to present your work before 2 October 2025 at 11.59 pm (GMT). Learn more and apply at phmuseum.com/w25.

Lucija Rosc (b. 1995) is a visual artist based in Ljubljana, Slovenia. Rosc graduated in photography from the Faculty of Applied Sciences VIST in Ljubljana in 2018 and earned her master’s degree in Visual Communication Design, with a focus on photography, with special honors from the Faculty of Fine Arts and Design (ALUO) in 2022. Rosc received the UL ALUO Prešeren Award and was a nominee for the 2024 OHO Award, Slovenia's premier national recognition for young visual artists. Rosc's art practice combines an investigative approach with play, drawing inspiration from her childhood memories, family archives, and the environment in which she grew up. She has held numerous solo exhibitions, with her work featured in exhibitions across Europe and the USA. Additionally, Rosc's work has been showcased at prestigious contemporary photography fairs, including Unseen Amsterdam, Photo Basel, Viennacontemporary art fair and the Art Salon Zürich, among others.