Last Year Recipients On Receiving The PhMuseum Women Photographers Grant

-

Published30 Sep 2025

-

Author

- Topics Awards

Marisol Mendez, Sara Abbaspour and Sara De Brito Faustino discuss how the grant, which is currently accepting new submissions, impacted their work, disclosed new horizons for their practice, and give advice to prospect applicants.

As the PhMuseum 2025 Women Photographers Grant is now open for submissions, we reached out to last year's prize recipients to hear about their experience, and touch base on their current work.

Could you describe the tipping point that took you from knowing about the grant to actually starting the application?

Sara De Brito Faustino: I've been working as a teaching assistant at the school where I graduated in 2023. One of the tasks I was assigned was to curate and send newsletters about grants and photography contests to the alumni. The tool I used the most was the PhMuseum website. While browsing different grants, I was drawn to this one because it was exclusively for women. I loved the idea and the possibility of shifting the balance toward gender equality in the art world through women-only contests.

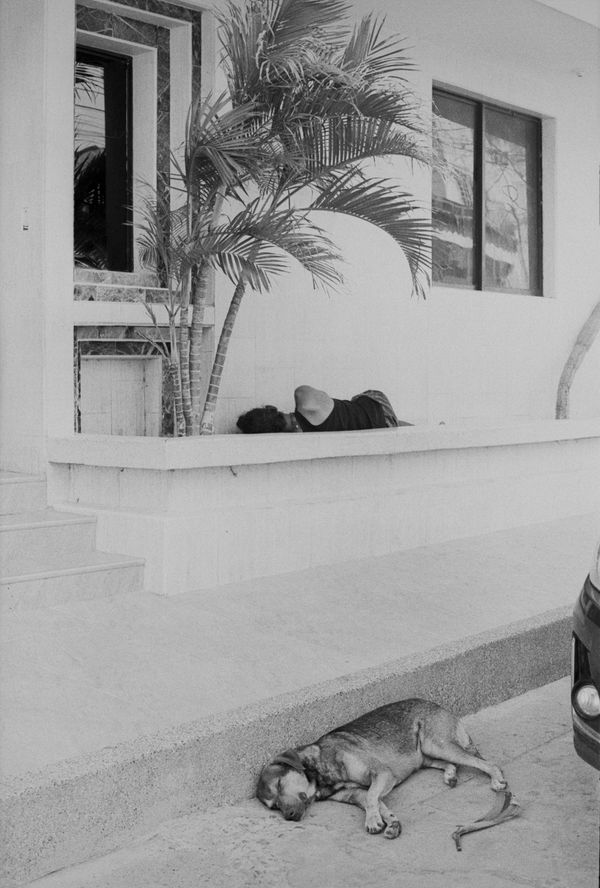

Sara Abbaspour: When I first learned about the grant, I felt compelled to sit down and shape the photographs into a sequence that could carry both clarity and ambiguity. The initial edit took hours, and many more followed, as I searched for a rhythm between cohesion and the nonlinear threads I wanted the work to hold. Writing became an extension of that process—drafting and redrafting to clarify my intentions while preserving the mystery essential to the images. Because the project emerged from a charged environment and is deeply personal, I was conscious of how easily it might be reduced to predetermined categories. The application became a way to articulate the work’s intimacy while protecting its openness.

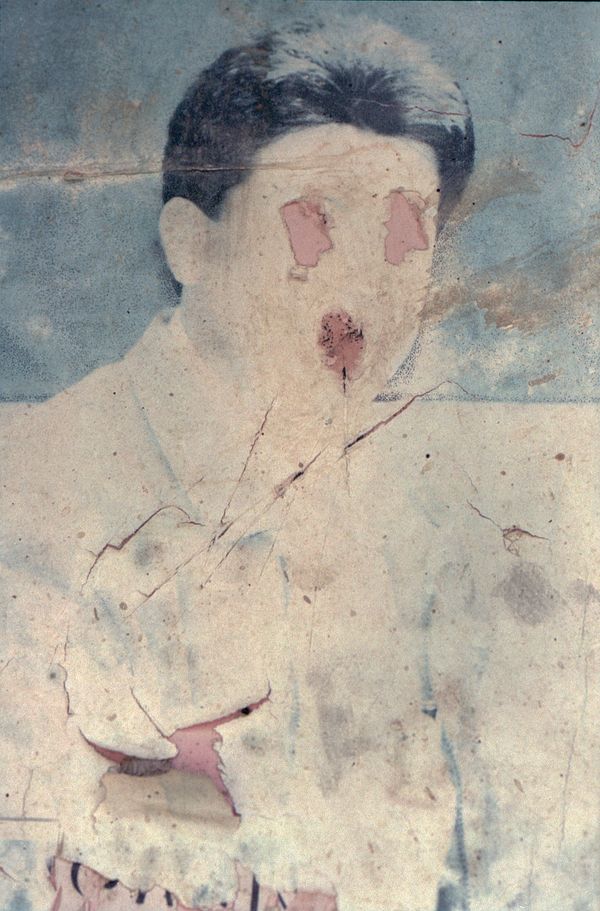

Marisol Mendez: I had been following PhMuseum’s Women Photographers Grant for a while and admired the diversity of practices it supports. With Padre, I felt I had reached a moment where the work needed to start a conversation outside my own studio. The tipping point was realizing that applying wasn’t only about recognition but also about testing the project in dialogue with others. I told myself, why not put it forward and see how it resonates? That shift, seeing the application as part of the process rather than just an outcome, was what pushed me to finally sit down and do it.

Every significant project comes with its challenges. What were the biggest obstacles, logistical, conceptual, or emotional, that you encountered while developing this body of work, and how did you navigate them?

Marisol Mendez: The biggest challenge with Padre was the emotional weight of the subject. It is such a personal project that at times I felt too close to it, almost blinded by the intimacy of the story. Navigating that meant finding a balance between vulnerability and distance so that the work could resonate beyond myself. On a practical level, I self-finance my personal work, which means resources are not always readily available. This can make the logistical side quite challenging, especially when working between different countries. That is why grants like this one are so important: they give the project the support it needs to move forward. What helped me through it all was leaning on research, conversations, and the act of photographing itself, which became a way to process and to keep building the work.

Sara De Brito Faustino: The most difficult aspect of the series was working with miniature objects. I started building maquettes of my interior as a way to regain power over difficult memories. But I found myself struggling with control, trying to move tiny objects. I used tweezers, and it was a really painful and emotionally draining process. Looking back, though, I think this is what gives the series its charm. The scenes appear to be in an unstable equilibrium, which perfectly translates the experience of living in a dysfunctional home.

Sara Abbaspour: One of the main challenges was sustaining the project’s complexity without letting it collapse into a single reading. I wanted the photographs to hold multiple registers at once—drawing from the cadences of Persian poetry, the visual languages of global photography, and the sensibilities of independent cinema. The aim was to create work rooted in place but also resonant with a sense of placelessness and timelessness. Balancing these tensions shaped every stage of the process. Alongside the conceptual demands, I also confronted the practical realities of a political climate hostile to free movement. As an Iranian artist, I encountered travel restrictions and bureaucratic delays that affected production. Navigating these obstacles required persistence and adaptability, but ultimately deepened my commitment to allowing the work to remain open, layered, and resistant to confinement.

How has receiving this grant impacted your career and the trajectory of your project? In which ways did the grant contribute to your research?

Sara Abbaspour: The grant has supported this project in essential ways. Beyond its financial support, it offered a form of recognition and encouragement that affirmed the significance of the work. It also gave me the momentum to move confidently into the next phases I have been planning. In particular, the support has enabled me to refine a photobook draft, which is now approaching the stage where I can share it with publishers. The grant made it possible to plan strategically for the project’s continuation and long-term trajectory.

Marisol Mendez: More than the money itself, it was the recognition that made me feel my work had value outside of my own circle, which gave me confidence to keep investing in it. The grant also created visibility and momentum around the project, opening doors for conversations that helped me refine my research. Thanks to the platform’s reach, the work began circulating among new audiences who might not have otherwise encountered it, which expanded its resonance and impact. In a way, it was less about completing the work straight away and more about realizing that the project deserved to be pursued with commitment and depth.

Sara De Brito Faustino: Another difficult part of the project was dealing with my own expectations and the perfectionism that follows me in every aspect of life. The grant was one of the first recognitions I received just after graduating and stepping into the art world. It meant so much more than the financial support; it meant that a jury of professionals considered my work interesting. It helped me believe in the project a little more and appreciate how it resonates with the public.

On a personal level, what did this recognition mean to you? Has your perception of your own work evolved since then?

Marisol Mendez: On a personal level, the recognition felt like a turning point. It shifted the way I looked at my own work, from something intimate and almost fragile to something that could speak to others with strength and relevance. Until then, I often questioned whether a personal exploration could matter to others. The grant quieted those fears and gave me the courage to treat the work with the seriousness it deserved, to trust that my father’s story, and my perspective, could hold relevance in a larger context.

Sara De Brito Faustino: The grant really gave me self-confidence in my work and its potential to resonate with an audience. At the time, I was preparing my first solo show with these images, and I became very excited to share them with the world. It was then that I started to understand that this job is not only about satisfying my own vision of what I want to photograph but also about sharing it with an audience who is often far less critical than I am. I am still learning to let go and actually like my own work, but it remains challenging. I think part of being an artist is to always dislike our work a little bit.

Sara Abbaspour: I believe that staying true to the integrity of the work—remaining accountable to its conceptual and aesthetic framework—is a complex and rigorous process. It continually exposes the vulnerability inherent in decision-making, where self-criticism, excitement, exhilaration, and doubt coexist. Receiving this recognition has been deeply meaningful, both as affirmation and as encouragement to continue refining the project. I am grateful for it, and I remain committed to the values I have discovered within the work while striving to strengthen it where it still falls short.

From your perspective, what are the most significant barriers to equity in photography today, and how do grants like this one help to dismantle them?

Sara De Brito Faustino: I think being a woman in the art world is still very difficult because it remains a male-dominated field. In my five years of studying photography and working as a teaching assistant, I noticed that in class there are always far more women students. But when you look at the professional field, whether in commercial photography (fashion, jewelry) or the arts, there seem to be more men (that succeeded and are known for their craft). Women become invisible, as happens in many other career paths, though I can see this slowly shifting in recent years. A grant like this is very important and contributes significantly to that change.

Marisol Mendez: One of the most significant barriers in photography is its inaccessibility. The medium is inherently elitist: equipment, production, and even entry into certain spaces often require financial privilege or academic validation. This creates a landscape where many voices, particularly from the Global South, remain unheard. What I admire about PhMuseum’s platform is its genuine commitment to shifting that balance. Supporting both emerging and established practitioners from across the world, it helps diversify the field and proves that powerful work can come from contexts beyond traditional centers of power. Grants like this one don’t just provide resources; they open doors to visibility and legitimacy that can be transformative for artists who might otherwise remain on the margins.

Sara Abbaspour: Photography, since its invention, has been an artistic medium accessible to many—women, marginalized communities, and those not taken seriously within traditional art circles. It opened possibilities for multiple visual languages, experiments, and forms of expression. Yet art institutions were much slower to acknowledge this breadth. For much of its history, the photography that was canonized remained overwhelmingly masculine and Euro-American in focus. Grants like this one, with their commitment to insightful juries, help shift that imbalance by creating platforms that recognize women photographers who bring new perspectives and affirm agency, while resisting the narrow identity politics and subcategorizations that too often confine how such work is received.

The application process itself can be a moment of reflection. What did you learn about your own work while preparing your submission? Do you have any practical advice for prospect applicants?

Sara Abbaspour: There were many things that unfolded while preparing my submission. I reflected on how the research phase of the project gradually gave way to trusting intuition during production, and on the importance of finding the right language to articulate the work. Sequencing was especially rewarding—it remains my favorite part—while writing proved more difficult, though ultimately necessary. I also realized how essential it is to have a community of trusted friends who can be both deeply supportive and uncompromisingly honest in their critique. Finally, I was reminded of the value of looking outward, continually drawing inspiration from the long list of artists whose practices I admire.

Sara De Brito Faustino: I think I reflected more on the medium of photography itself than on my own work. Photography is a sharing-based medium, and platforms like PhMuseum, even if they don’t offer the polished white-cube setting and perfect exhibition shots, have the power to reach a wider audience, be less elitist, and last over time. Submitting my work through the website allowed me to see it in a layout, which made me think about its sharing potential. That’s when I started seriously considering turning the series into a book.

Marisol Mendez: Preparing the submission for Padre pushed me to step back and reconsider not just the visual language of the project, but the emotional undercurrents that drive it. In the process, I rediscovered how intertwined my personal history is with broader cultural narratives, how the intimate can speak to the collective. Crafting the application required me to articulate that connection with clarity and intention. One thing I learned is that the editing and sequencing process can be a form of storytelling in its own right. Padre is a layered project, and distilling it down for a submission made me reflect on which layers were essential for others to access its meaning. As for advice to future applicants: be honest and intentional. Don’t try to mold your work into what you think the jury wants to see. Instead, focus on what makes your voice unique. Pay close attention to sequencing and text; they're tools to build a narrative arc that feels coherent and true to your message. And give yourself time. Reflection doesn’t happen in a rush.

Are there any new steps you plan to take to further develop or share this body of work?

Sara De Brito Faustino: As I mentioned, the application process sparked the idea of making a book. Since then, the body of work has expanded from 22 to 65 images. I am planning to launch this first monographic book this November during Paris Photo’s opening week. I’m very excited, as this marks another step in sharing my work and making it accessible.

Marisol Mendez: Padre is becoming a photobook, which feels like the most honest way to honour the work. The book will allow the story to breathe in a slower, more intimate rhythm. It's a chance to revisit the material with fresh eyes and give it a lasting, tactile form that people can live with over time.

Sara Abbaspour: Yes. As I mentioned earlier, I am currently working on a potential photobook, with the working title Floating Ocean. At the same time, I am planning to develop new bodies of work that build on what I have learned through the many stages of creating this project.

--

The PhMuseum 2025Women Photographers Grant is currently open for submissions. Its aim is to empower the work and careers of female and non-binary professionals of all ages and from all countries working in diverse areas of photography. To learn more and apply, visit phmuseum.com/w25. Final Deadline: 2 October