Inherited Shadows: Marisol Mendez's Journey Through Masculinity and Its Haunting Legacy

-

Published8 Apr 2025

-

Author

- Topics Archive, Contemporary Issues, Social Issues

Weaving together photography, archives, and letters, Padre examines the complexities of masculinity—how it is inherited, performed, questioned. Mendez’s images linger in the spaces between power and vulnerability, myth and memory, presence and absence.

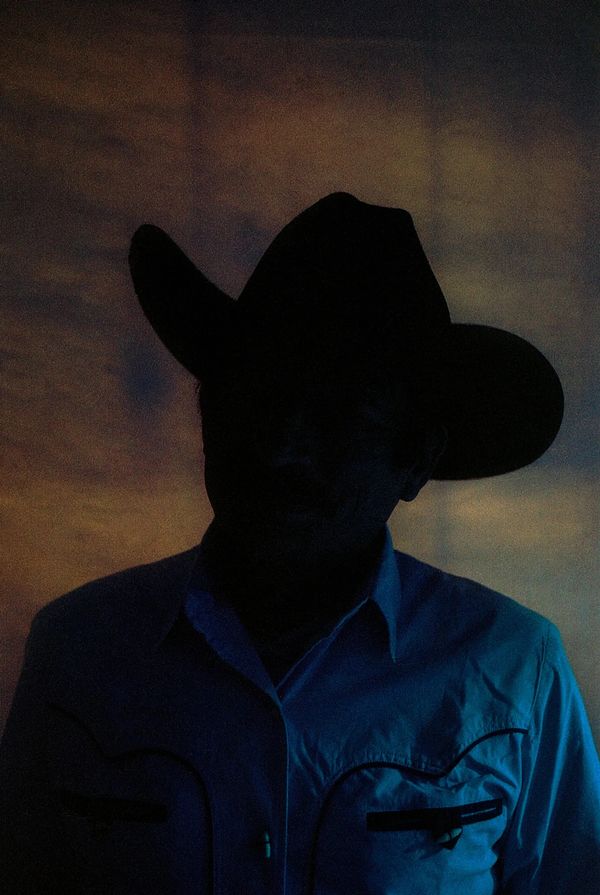

The cowboy stands in shadow, his face obscured, a silhouette without a name or identity. In Marisol Mendez’s work, this absence is deliberate—an invitation to consider not just the man, but the symbol he represents. The cowboy, with his rough exterior and untamed independence, is an enduring mark of masculinity, yet he is also a ghostly figure, his identity blurred. In Padre, Mendez unravels this duality, exploring the ways masculinity is both present yet dissolving. Through photography, family archives and letters, she questions the roles men inherit and the power structures they sustain. Her work does not offer answers but lingers in the spaces between—between tenderness and control, tradition and transformation, the personal and the collective.

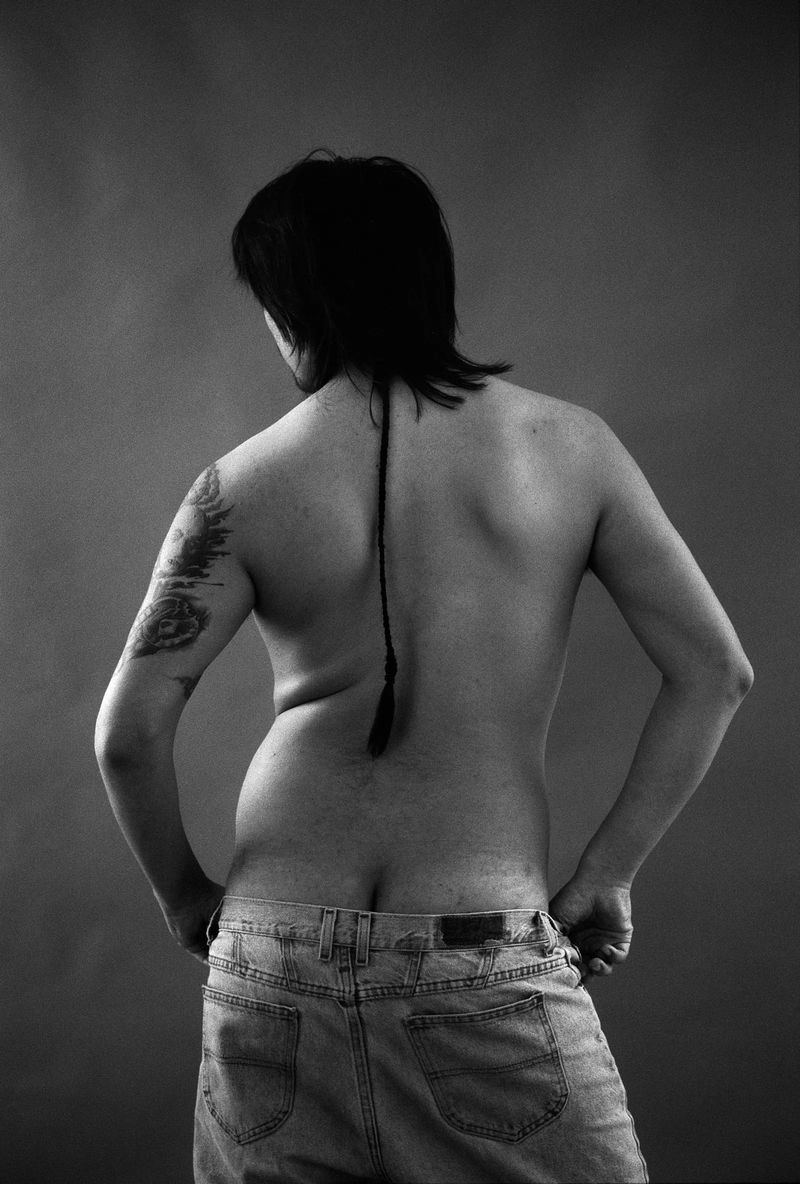

At the heart of her exploration lies a fundamental question: what does it truly mean to be a man, and how does one become one? Mendez draws a parallel to Simone de Beauvoir’s famous question about becoming a woman, highlighting in Padre the idea that gender is not innate but performed and indoctrinated. Historically, women were confined to domestic spaces and reproductive roles, forcing them to push against rigid structures and redefine womanhood. In contrast, many men, shielded by patriarchal privilege, often lack the urgency to interrogate their own identities. This privilege, while harmful to all, insulates those who benefit from it, preventing the discomfort that drives transformation.

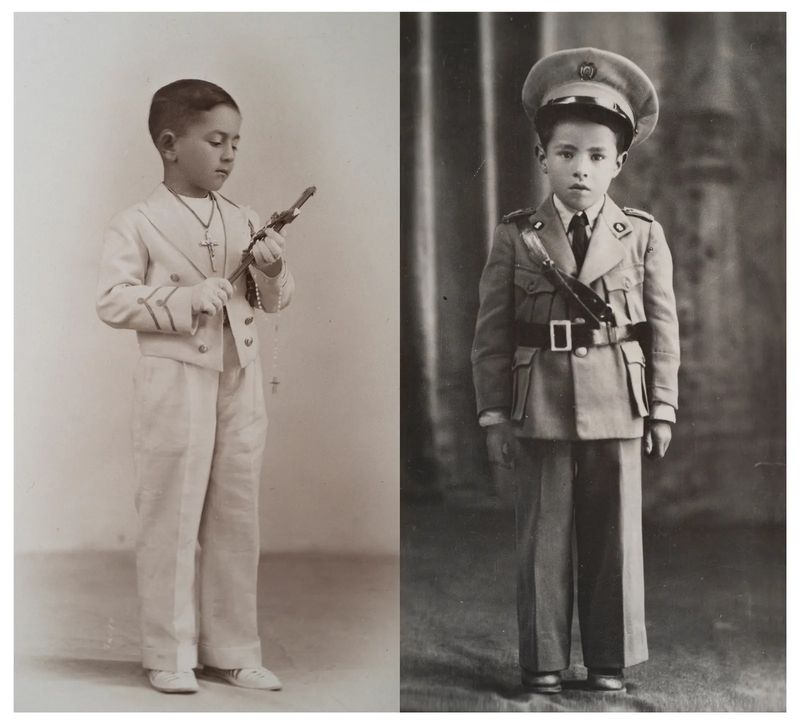

This is why Mendez is drawn to the origins of masculinity—where it is learned, internalized, and performed. Her project begins with words—specifically, the letters exchanged between her father and grandfather. Unlike her previous reflections on femininity, which focused on how women are represented in images, Padre emerged from written documents, shifting her exploration of masculinity toward language and personal narratives.

Before his passing, her father left behind a collection of letters. A few years later, Mendez came across a letter her grandfather had addressed to her father while working as a diplomat. The letter’s duality struck Mendez. On one hand, her grandfather’s words were sentimental—expressing deep affection for his son. Yet, he also embodied a traditional masculine ideal: a politician, a fisherman, a hunter—someone shaped by the very notions of machismo she seeks to unpack—an inheritance of expectations passed down through generations.

This theme of inheritance plays out visually in Padre. Many of Mendez’s images depict decay and erosion, reflecting the slow deterioration of hegemonic masculinity. Its ideals, outdated and rotting, persist like relics of the past. One photograph features a political propaganda flyer, its subject’s eyes hollowed out, its mouth rotten: traditional masculinity is fading, yet somehow still haunting.

To further unravel identity, Mendez weaves mythology into her work, using fiction as a lens rather than strict ethnography. Myth becomes a bridge to reality, not an escape from it.

“I love that these images can be read one way or the other,” she says. “Because they speak to something very real.”

In one photograph, a dancer portrays the sun, a male deity in a religious festival. Yet the dancer’s soft, almost feminine expression and pastel-adorned costume contrast sharply with the severity of traditional masculinity. Mendez relishes this juxtaposition, using humor to highlight the absurdity of rigid gender expectations.

Animals also appear in her work as metaphors for violence and dominance, exposing how harm is often normalized in patriarchal systems. A photograph of rabbits in soft pastel hues initially seems gentle, but a closer look reveals they are caged—raised for consumption. Similarly, the image of a buried llama fetus, part of a ritual for good luck, challenges perceptions, encouraging deeper reflection. In these juxtapositions, Mendez urges viewers to question the stories beneath the surface—how acts of violence and control are often unseen, embedded in cultural practices.

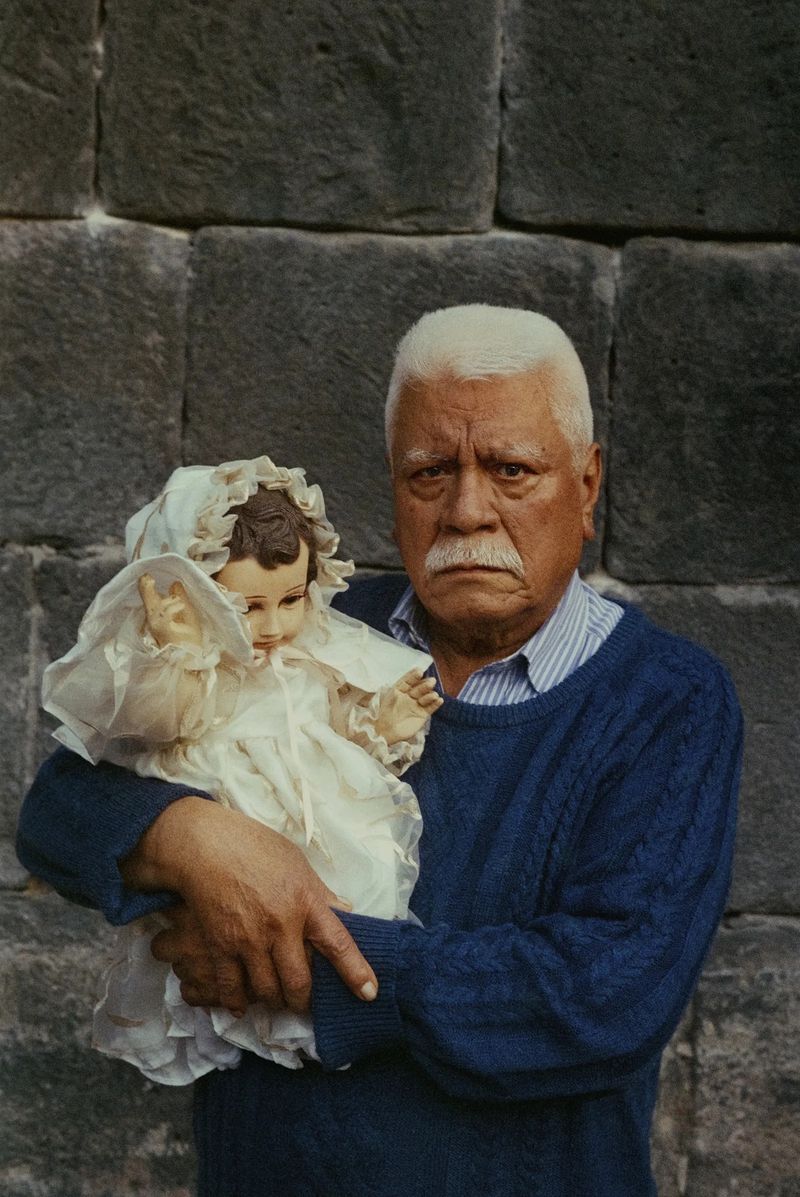

One of the most striking images in Padre captures a man holding a baby Jesus doll at a religious celebration. The doll is dressed in an ornate gown, cradled protectively in the man’s hands. Yet the man’s severe expression contrasts sharply with the doll’s innocence, creating a layered tension—at once protective and intense. Mendez appreciates this ambiguity, allowing the image to hold multiple, even contradictory, meanings.

“If life were black and white, it would be easy. You’re either good or bad,” she says. “But life isn’t black and white. It always has hues. That’s why I think it’s important to make complex images—because reality is very complex.”

--------------

All photos © Marisol Mendez, from the series Padre

--------------

Marisol Mendez is a photographer and researcher from Cochabamba, Bolivia. She uses her camera to study the tension between truth and fiction, the tight relationship between what a photograph creates and the (sur)real it comes from. Through research-driven and self-initiated projects, she challenges traditional representations, creating layered narratives rich in meaning. Find her work on PhMuseum.

Lucia De Stefani is a writer and editor focusing on photography, illustration, and everything teens. She lives between New York and Italy. Find her on Instagram and Twitter.